Jammie Holmes, “Zebra,” 2022, video, Total runtime: 4:17 minutes, (JHO.19651), Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen. © Jammie Holmes

Jammie Holmes’ paintings have a way of inviting you in. Emotive and allegorical, they depict everyday moments with extraordinary feeling. In What We Talking About at Marianne Boesky Gallery — the artist’s debut exhibition in New York — eight large-scale works (as well as a mesmerizing video installation) evoke memories and reveries of Holmes’ childhood in Thibodeaux, Louisiana; a place so deep inside him, it takes up the whole gallery wall. (One of the show’s paintings stretches 7 1/2 feet tall and 24 feet wide.)

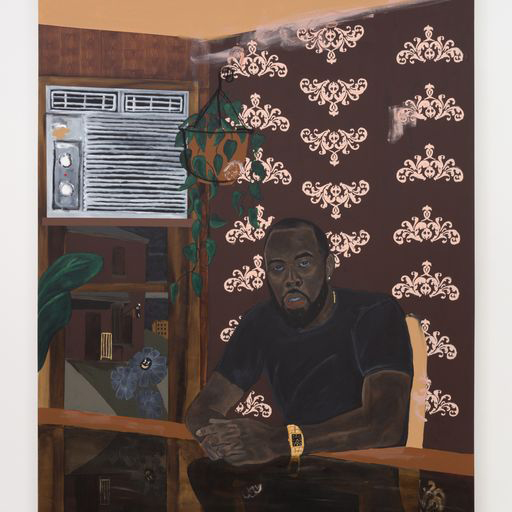

Rich earth tones dominate the scenes Holmes’ subjects inhabit — indoors, outdoors, sometimes both at once — with aberrant winks of color that add an element of transcendence. Images of red Solo Cups, black-and-white tiles, and glittery gold frames recur with enough frequency to take on a talismanic energy. Even so, there is a casual quality of downtime in these paintings, of people just living their lives. Holmes often appears in the work, as a self portrait and portrait of selves: a stand-in for past lives and voices that haven’t been heard.

Holmes began painting in 2016, after moving to Dallas from Louisiana, where he had worked in the state’s oil fields for more than a decade. Things moved swiftly for the self-taught artist, whose work started gaining attention even before signing with the Detroit gallery Library Street Collective, and now, Marianne Boesky Gallery as well. His work has been shown both here and abroad, and is also included in the permanent collections of several museums — a fast-moving timeline, he tells me, that came right on time.

Barbara Purcell (BP): I read that you didn’t go to your first art museum until after you were 30. Can you describe what that experience was like?

Jammie Homes (JH): It was a Kaws exhibition at the Modern [Art Museum of Fort Worth]. When I first walked in I just remember how big the pieces were — and the color scheme. That stuck with me. Other than that, all the artwork I ever saw was graffiti on trains with bright colors, or the Lowrider magazines I used to get. I had moved to Dallas and was working at a machine shop, and somebody told me about the Modern because I used to sketch at my desk. I’d never even been into a gallery. I just didn’t know anything about that stuff at all. We weren’t going on field trips in school to see art, we were going to the alligator farm.

BP: 2016 sounds like it was a breakthrough year for you: the move from Louisiana to Dallas, the Kaws show, and then loading up on your own art supplies! What was the timeline that followed?

JH: Within six months of me painting, I had already started — I hate to say it like this — selling to celebrity clients. Early on that’s how I knew it was my gift. I had sold a painting to a guy in the music industry and he spread the word and the whole music industry started buying my work. So before Library Street, I was already making sales and I was able to quit my job within two years and go full-time artist. There were already a lot of things happening because I was more business-minded than a painter. Working in the oil field, I was always in leadership roles, always the supervisor. Early on, I started treating my art like a business — I was running the company [laughs]!

But when it comes to creating the art, that part’s not a job, that part is like poetry for me. When I’m painting, it’s a feeling that’s hard to explain because it connects my hands, my eyes, and heart at the same time. Like the holy trinity of things. So the timeline was right on time. It’s hard for me to feel like things moved too fast, because what is fast or not moving fast enough? What is meant for you is meant for you.

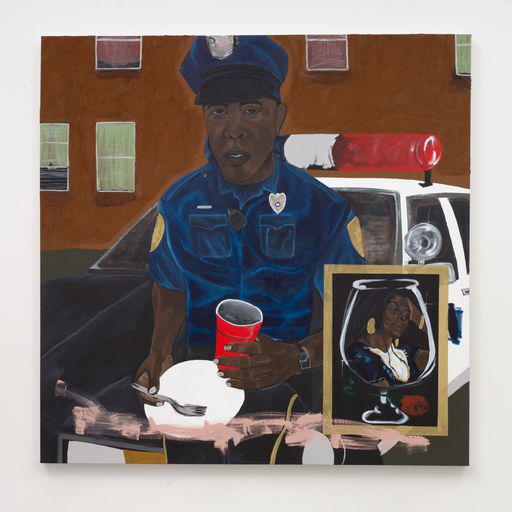

Jammie Holmes, “Fred Hampton,” 2022, acrylic, glitter, gold leaf, and molding paste on canvas, 90 x 90 inches, 228.6 x 228.6 cm, (JHO.19511), Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen. © Jammie Holmes Photo credit: Lance Brewer

BP: Did you always kinda know you were an artist?

JH: I could sketch anything from a real early age. I was always different compared to the other kids when it came to sketching and coloring and lines. By the time I was in sixth grade I was able to sketch people the way they look. Matter of fact, the reason that came about was because my grandmother had a picture of her mom that she really loved. But she had three sisters, so she asked me to sketch the picture of my great grandmother. One turned into three, then four [laughs]. The last time I went to her house I think she had the sketch on the wall instead of the original picture.

BP: You’ve said in other interviews that growing up in Thibodeaux, Louisiana meant growing up fast. I see a lot of tenderness and nostalgia in your paintings. What do you want us to know about the people in them?

JH: It’s not so much about the person in the painting, it’s more about different emotions. What does sadness look like? Or happiness? Not just the facial expression, but what does that look like in a physical form? The more I paint the more I start feeling with my eyes. So now that I’m feeling with my eyes instead of with my hands it’s just different. Those figures are more of a stand-in for an emotion. I want to normalize Black men just being themselves, no matter what it is: happy, sad, throwing dice, doing backflips — doesn’t matter, just being part of the world. We already have enough of the “tough Black man” image, we don’t need to see that all the time. I just want to show regular everyday people. My work is not about the South, my work is just across the world. The Black man symbolizes minorities, period. I’m just speaking to people outside of the norm of white America. When the country was created, that’s who it was for. And ok, but this is where we’re at now.

BP: Tell me about the painting in this show, Assata Told You. I love how the cop in uniform is just enjoying his plate of food like he’s at a cookout.

JH: Right! Because that was normal where I was from. At home, we don’t get tense when we see cops. Cops already know you, and live down the street from you. Thibodeaux is so small that their kids go to school with our kids. It’s not like in big cities, where they get suspended and go hide upstate. I painted the cop with the intention of an everyday person — he’s probably acting as the security at a family reunion. Just chilling, talking with people and eating food.

Jammie Holmes, “Gold Geneva,” 2022, acrylic, oil pastels, glitter on canvas, 84 x 60 inches, 213.4 x 152.4 cm, (JHO.19501), Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen. © Jammie Holmes Photo credit: Lance Brewer

BP: A lot of your paintings have smaller portraits within the painting, including this one. Who is the woman you’re, I guess “toasting” in that brandy glass?

JH: That is Assata Shakur. She’s an America’s Most Wanted person, from a shootout in New York in the 70s, I believe. I don’t know the whole story off the top of my head. But a cop got killed and she moved to Cuba, where they protected her. There’s never justification for murder unless its self defense, but I felt like that was a moment where she defended herself, but was on the opposite side of the law. So that’s the reason I put the cop in there. Unfortunately there were a lot of lives lost around that time. Fred Hampton [the Black Panther Party leader] is in another painting in the show — they killed him as a kid, just for speaking out. I’ve always looked up to those type of people. I learned about Bob Marley at an early age. Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, too.

BP: There are recurrent images in your work, and I’m curious about those smears of pink paint.

JH: Ok, yeah. In my older works it used to be blue. I was at a museum one day and I was looking at the artists from the Renaissance and they were signing their names on the front. I thought it was cheesy. I don’t want people to know my name is Jammie Holmes, I want the art to speak for itself. No offense to nobody who does that. So it’s a signature move for myself, me blessing the work. It’s not on all of them, but I like to play with it. It also helps balance out the work for me. Sometimes a painting won’t even look complete until I do that.

BP: You’ve got some striking cartoon-ish eyes in this show, I’m thinking of the black flags and the black daisies. Tell me about their presence in these paintings.

JH: The eyes came because of the idea of seeing things from the perspective of a Black man as a Black man. Some of the flags use the original Pan-African colors — green, red, and black — but the eyes on the black flags are a challenge for the world to start seeing life through another person’s skin. Then there’s a quote about “the rose that grew from concrete,” but there is no way in life I’m ever gonna see a rose do that — only weeds. If you think about it, weeds are always being punished. They’re always being sprayed and killed. But they always grow right back unless you get at the root. So I created the black daisy because it came from that weed growing out of concrete. That’s how I always felt. I grew out of a hard shell to where I’m at now. The daisy’s eyes and face, that’s tapping into the idea of the Jim Crow era. When they painted blackface on toys and cartoons, so it’s basically taking that back.

Jammie Holmes, “Assata Told You,” 2022, acrylic, oil pastels, glitter and sand on canvas, 71 7/8 x 72 inches, 182.6 x 182.9 cm, (JHO.19500), Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen. © Jammie Holmes Photo credit: Lance Brewer

BP: In addition to this show’s paintings, you have a four-minute video installation where you’re sitting in a chair while all sorts of media footage gets projected onto you — and there’s a bench in the space for viewers to sit there with you. What inspired this?

JH: I’ve always wanted to have a sit-down as a Black man and just get it all off my chest. Outside of being polite, how many white guys just sit down and talk with a Black man in a month, or vice versa? Just talk about upbringing, parents, things that have made them change they’re thinking. How many people are doing this sort of thing? So this is my way of doing it. We’re sitting down together and you’re gonna see what I’m watching and feeling. That’s why I have this look on my face of just staring, like I’m enduring all of it and I want people to sit down and endure it with me. It’s almost like a hug. When you hug someone and say nothing, you just feel them.

BP: There’s a lot of video footage washing over you in the course of those few minutes: is there one clip that sticks out for you?

JH: Two things. One is a Ku Klux Klan member holding hands with his son and his son has that hat on, too. Look how young this kid is — and it’s the 1960s — so that kid is still alive right now! The other, leading in, is the little girl who smiles. She and I shared eyes for a moment. So the two kids, the two types. There’s moments where it’s black and moments where it’s white on my face at the same time. That’s why I called it Zebra. Like the yin and the yang: black and white, good and evil — but it still makes up one thing.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What We Talking About is on view through October 8 at Marianne Boesky Gallery in New York City.

1 comment

Very nice interview. Thanks Ms. Purcell.