There is something to be said about seeking a slower pace for our art activities. It seems after emerging from the pandemic-led social distancing, isolation, vigilant mask-wearing, homebody life-style, we are again going 90 miles per hour, multi-tasking, and art-opening socializing as before March 2020. One month I was making life drawings from walks around nature, the next month I’m driving to several openings per night, worrying about my place in the arts-social-ecosystem and wondering where my artistic ambition went, and questioning why I stopped doing work with an eye toward capturing attention. One feels they had to jump back on the treadmill we call our art careers.

However, a pandemic-era outlook could be worth maintaining. A nostalgic view about what we experienced over the last few years could be a lens to how we see things differently in the studio, and how we consider the work of our contemporaries. This is my approach to Pulp, the current exhibit at Jonathan Hopson Gallery. In it are six artists that the Houston arts community has come to know through some very different approaches and mediums. With some artists, it is hard to recognize their work, considering that we’re more familiar with other elements of their output. With others, we see new possibilities and permissions.

Pulp features artists Liz Rodda, Lauren Moya Ford, Hong Hong, Guadalupe Hernandez, Brandon Tho Harris, and Troy Dugas. Each has deep associations with the contemporary art world of Houston and the Southwest, while maintaining a practice where ties to studio and native connections have primacy.

Fixing my post pandemic eyeglasses, I take my time to consider each artist individually, rather than my pre-pandemic inclination of asking, “ok, where’s the moving images, the flash and the bang?”

Left: Liz Rodda, “Untitled” (detail) 2021, acrylic paint on paper, 18 x 24 inches; Right: “Untitled” (detail), 2021, acrylic paint on paper, 30 x 23 inches. Photo courtesy Henry G. Sanchez

Liz Rodda has a well-deserved reputation for large scale, multi-media installations. Video features prominently along with sound and immersive experience in her body of work. Instead of digital flat screens, this show features two modest-sized acrylic paintings on paper. I asked the gallerist if they happen to be stills from her videos. “Nope,” she said, telling me that each are completely independent from her installations. Both were painted this year, and they show a confident hand and signature. It made me appreciate the freedom of permission she gave herself to make and exhibit work that would not normally fit in the oeuvre; a risky move.

Left: Guadalupe Hernandez, “Quetzacotl” (installation view) 2022, Papel picado installation, dimensions variable; Right: “Quetzacotl” (detail), 2022, Papel picado installation, dimensions variable. Photo courtesy Henry G. Sanchez

Hanging from above was the papel picado (cut paper) installation of Guadalupe Hernandez. This traditional folk-art method is transformed in Hernandez hands. Known for his labor-intensive cut images, based on street photography of Mexican culture, Hernandez also turns the tables on the viewer in this show. By presenting something more voluminous, rather than a singular, discrete papel, one imagines an inverted floating bed. Different from his previous papel iterations, the Quetzacotl sculpture is named after the plumed dragon of Aztec/Mayan legend. It is an appropriate placing — it exchanges the heavy connotation of death and resurrection for that of “annunciation.”

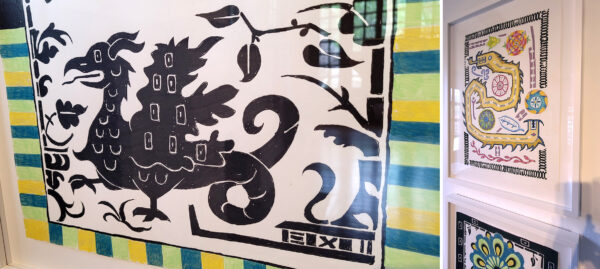

Left: Troy Dugas, “Tapestry Concept Design #9” (detail), 2019, colored pencil, markers, gesso, paint pens on paper, 24 x 19 inches; Right: “Tapestry Concept Design #8” (installation view), 2019, colored pencil, markers, gesso, paint pens on paper, 24 x 19 inches. Photo courtesy Henry G. Sanchez

Dragon and mythological images are reflected across the room in the work of Troy Dugas. He is from a small town in Louisiana, and spends much of his art career in Baton Rouge and New Orleans. The four mixed media work on paper were described to me as potential studies for much larger tapestries. Dugas, like Hernandez, has an intensive practice cutting, stamping, weaving, and gluing hand printed and painted paper into large scale collages representing modern-day mandalas. Lately he has replaced the hand cutting and painting with actual weavings. Again, a laborious method, but it is not reflected here. These fresh, spontaneous drawings demonstrate how a letting-go of one’s reputation can lead to surprises.

Brandon Tho Harris, “H-TOWN TILL I DROWN” (details), 2022, Joss paper car, paper clay, silver paint, vinyl decal, mirror, 25 x 15 x 8 inches. Photo courtesy Henry G. Sanchez

A surprise in the show is a small sculpture by Brandon Tho Harris. Part of my initial attraction to it was the stand created by the gallerists for the piece, which is made of tires. Then, I was drawn to the 24-inch-long paper car sculpture with spinners (hubcaps). H-Town till I drown is deceptive. At first glance it looks like a pre-made kit for hobbyists. But here, a little research is required. Harris’ body of work delves into his Vietnamese heritage, culture, and auto-biography. Though he’s mostly a photographer, for him this piece is a small point of departure, and takes ownership of a joss paper car meant for blessing ancestors. By creating tiny protruding spinners for the car, Harris fuses his own cultural references with Houston SLAB car culture. The piece is indicative of how we assume new influences from our melting pot city.

Hong Hong, “Three” (details), 2022, repurposed paper, yarn, water, sumi ink, sun, dust, hair, pollen, 56 x 111 inches. Photo courtesy Henry G. Sanchez.

The largest piece in the show is Three by Hong Hong, who splits her studio practice in various cities across the country. Standing at an impressive 9 feet long, it is made from repurposed paper and other natural elements. She uses the traditional Chinese paper making process to create grand-scale work. Three’s intricate patterns connote circuitry, but the artist intends them to be more like a complex of maps. The sculpture is a tryptic, but originally the pieces were 3 separate works, which is why I consider it to be an intimate piece, and also why it fits well with the rest of the show. To achieve intimacy while having a peripatetic practice making large-scale works is a challenge and an envious skill.

Left: Lauren Moya Ford, “Hands to the Light,” 2022, glazed ceramic dish, 1.5 x 5.5 x 5.5 inches; “Hands to the Light,” “Mi Clavel,” “Desert Rose,” “Camellia Bowl,” each 2022, dimensions variable. Photo courtesy Henry G. Sanchez

We are all guilty of the urge to capture a smart phone image of our hands holding, caressing, or touching an object. While a digital version is ubiquitous and trite, Lauren Moya Ford’s hand-built ceramics make the gesture more apt to my notion of slowing down. Her vase and bowls contain the same sense of affection as many of her works on paper: they are down-to-earth and concerned about observation. These are works where the signature and imprint of the artist, rather than the method, are on display. She imperfectly builds a clay vessel, and scores and paints the images of flowers and hands holding botanicals. Nothing factory made here. Starting with works on paper and then moving to ceramics is a natural path for Ford’s practice, and it produces abundant results.

Speaking with the gallerist Debra Barrera, also an artist, I asked whether the pandemic-era subconsciously influenced the work in the show. Not every artist changed during the pandemic, she says. Her choices were more about the feeling of things made in the moment. Whether it was mark making on paper, ceramic building, the spontaneous gesture, or reconceptualizing the studio expectation, all the artists are giving themselves permission to move away from what they are comfortable with. Overlapping play and a slower process is what brought the work together. The curating took the same approach: see what happens when they come together.

Jonathan Hopson Gallery one of Houston’s gallery gems. One of the survivors after the pandemic. It’s an intimate space that acknowledges artists of different generations, backgrounds, and conceptual approaches. The gallery ethic is to show how these differences can interact and be conversant in similar ideas. Barrera said the last two years were tough. I’m glad they are still here.

****

Henry G. Sanchez is a Houston-based interdisciplinary artist. Sanchez is the founder/director of the BioArt Bayoutorium — a social-practice, bio-art project about local stewardship of Buffalo Bayou in the 2nd Ward of Houston; and L.O.C.C.A.: Law Office Center for Citizenship and Art – a platform where artists and social justice groups collaborate around issues concerning the Mexican American, Hispanic, latino/a/x/e issues in the 2nd Ward.