Installation view of Whitney Biennial 2022: “Quiet as It’s Kept” (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, April 6-September 5, 2022). From left to right: Lisa Alvarado, a selection from the series “Vibratory Cartography: Nepantla,” 2021–22; Matt Connors, “One Wants to Insist Very Strongly,” 2020; Matt Connors, Occult Glossary, 2022; Matt Connors, I / Fell / Off (after M.S.), 2021. Photograph by Ryan Lowry.

The 2022 Whitney Biennial in New York City, now in its 80th iteration, and after having been postponed by a year due to COVID, embodies, at its heart, a struggle for our soul.

Co-curated by David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards, the bulk of the exhibition takes up two floors of the Whitney Museum of American Art, and brings together some 63 artists from across a continuum of disciplines and generations. As a title, Quiet as It’s Kept is meant to infer disquieting truths hidden in plain sight: “The phrase is typically said prior to something — often obvious — that should be kept secret,” states the entrance wall text.

Let’s put this year’s Biennial into Texas terms: Floor Six of the museum is as solemn as the Rothko Chapel in Houston, while Floor Five is airy and light, like Ellsworth Kelly’s Austin. There isn’t much room for the outlandish on the sixth floor, with its black walls and sunless corridors subsuming visitors with last-ditch efforts to articulate what might already be too late, namely rising temperatures, raging tyrants, and depleting resources.

A pair of large-scale paintings by Denyse Thomasos (1964-2012) guard the entrance like sentries: Jail (1993) and Displaced Burial/Burial at Gorée (1993) are fiercely layered grids, done in black and white, dense in their charged geometry, to get at, what Thomasos once called, “the complexity of humanness.” Density and complexity typify the experience of moving through the sixth floor presentation, an exercise in adjusting one’s vision and circumspection.

Installation view of Jonathan Berger, “An Introduction to Nameless Love,” 2019. Photograph by Barbara Purcell.

Jonathan Berger’s An Introduction to Nameless Love offers a break from the dark with its textual tin sculptures illuminated by rods of white light. Based on a set of broad-ranging interviews conducted by the artist on the subject of non-romantic love, these wall manuscripts require one’s full attention when taking in each line. It is possible to do so, but improbable: the overload of information is an affront to the installation’s timed entry.

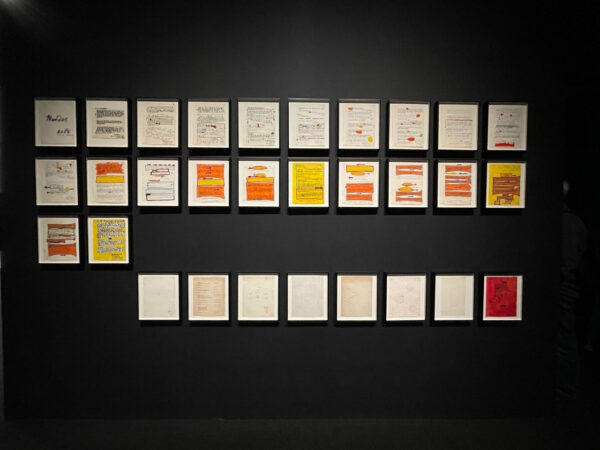

Another language-driven offering, this one by New York City poet N.H. Pritchard (1939-1996), features 30 framed sheets of drawings/writings quietly syncopating with one another on the gallery wall. Pritchard’s poetry, its spatial relationship to the page, reads like visual music. Handwriting and heavy marker (a paean of red, orange, and yellow) improvise, underline, and emphasize the poet’s typed-out prophecies: Do you think that they’ll make enough masks, one line innocently asks. Pritchard, who was a member of the 1960s Black writers collective Umbra, is not the only Downtown Manhattan experimental poet featured from the group.

Installation view of N.H. Pritchard, top three rows, “Pages from Mundus: A Novel,” 1970. Typewriting, ink, and marker on paper. Bottom row: “Untitled,” n.d. Typewriting on paper. Biography of public readings and discussions, 1965. “Untitled (Novae- and Gyre- ) (),” 1968. Typewriting on paper. “Untitled,” 1967. Typewriting on paper. “Prejudice,” n.d. Typewriting on paper. “Untitled,” 1968. Ink on paper. “Untitled,” n.d. Typewriting on paper. Red Abstract/fragment, 1968-69. Typewriting and ink on paper. Photograph by Barbara Purcell.

On the other end of Floor Six is a tribute to A Gathering of the Tribes, an arts organization founded in 1991 by poet and playwright Steve Cannon, a fellow Umbra writer and native of New Orleans who moved to New York in the thick of the civil rights era. Cannon, who died in 2019, provided a veritable salon for both the underrepresented and avant-garde; the Biennial installation reimagines his Lower East Side living room, including a signatory red wall (painted by the artist David Hammons in the mid-1990s), which oversaw the poetry and alchemy that Mr. Cannon, who was blind, effortlessly wielded for decades from the comfort of his couch.

Tribes is the bright spot on Floor Six, quite literally, backlit by some of the only museum windows readily accessible on this level. Other works include a three-channel video installation by Navajo artist Raven Chacon, with American Indian women performing songs of resistance; a five-part photographic series by Los Angeles artist Daniel Joseph Martinez that documents a “Post-Human Manifesto for the Future”; and a stunning clay sculpture by Canadian artist Rebecca Belmore of a faceless figure draped in a sleeping bag — humanity’s weary refugee — as thousands of empty bullet casings encircle the figure’s feet.

Installation view of Whitney Biennial 2022: “Quiet as It’s Kept” (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, April 6-September 5, 2022). Rebecca Belmore, “ishkode (fire),” 2021, clay and bullet casings. Collection of the artist.

Floor Five of the Biennial, in contrast to its upstairs neighbor, is filled with light and clarity — that aforementioned Ellsworth Kelly energy. Abstract sculptures and paintings situated throughout the open floor plan signify a refreshing return to the evocative after a years-long resurgence of figurative works. Themes on this floor are less digitally driven by video installations (though they do exist, including Mexican artist Andrew Roberts’ four-channel take on a NAFTA-induced zombie apocalypse).

Instead, we discover a love affair with materiality, such as translucent kitchen cabinets just beyond one’s reach, when one is a wheelchair user. The artist, Emily Barker, has also included a columnar stack of her photocopied medical bills titled Death by 7,865 Paper Cuts (2019) to illustrate the near-impossibility of bureaucracy when navigating the American healthcare system with a disability.

There are (subway) tokens of appreciation — tabletop piles of counterfeit coins illegally used as bus and subway fare — which artist Rose Salane acquired (64,000 of them) at an MTA Subway asset-recovery auction. And Aria Dean’s Little Island/Gut Punch (2022), a green-screen hued sculpture that also examines the concept of mimicry, its dented form a product of collision simulation. A Floor Five favorite: Charles Ray’s outdoor sculptures — post-pandemic Penseurs — three male figures posing in various states of urban ennui.

Of the Biennial’s three Texas artists, two have their work on view on Floor Five: San Antonio-born Lisa Alvarado and Houston-based Rick Lowe. The third artist, filmmaker and Dallas native Terence Nance, will perform an immersive experience titled 4th Dimension Trigger, 5th Dimension Trauma at the museum in September.

Alvarado, who now lives and works in Chicago, has a trilogy of textile paintings suspended in the center of the space. Their backs maintain a uniformity of color and pattern as each facade showcases a wildly hypnotic design. Vibratory Cartography: Nepantla (2021-22) resembles a regal display of flags (the fringes alone mesmerize) doubling as a stage backdrop. Nepantla, which means “in between” in Nahuatl, an Indigenous language from central Mexico, captures a certain spirit of this year’s Biennial, which calls the notion of jurisdiction into question: at least five of the participating artists are based outside the United States.

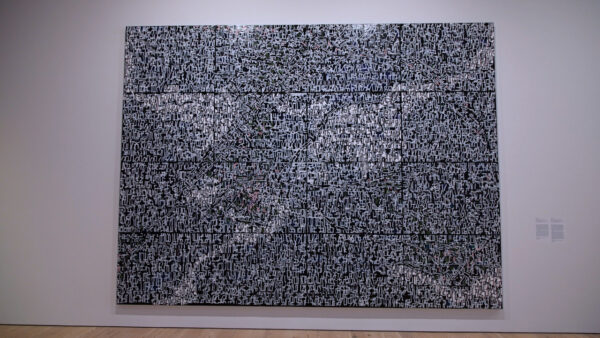

Rick Lowe’s large-scale painting Project Row Houses: If Artists Are Creative Why Can’t They Create Solutions? (2021) is a wondrous example of the artist’s domino drawings, based on the aerial (and spiritual) patterns of the game. The painting forms a capillary network of connections that resemble something of a city. Its title comes from a question once posed to Lowe early in his career, which, in turn, sparked a shift in his praxis: in 1993, he cofounded Project Row Houses, a public program that transformed 22 abandoned homes in Houston’s Third Ward into art studios and educational spaces. This work is a culmination of Lowe’s painting and social practice, giving off a colossal energy that must be experienced in person. How nice it is to be back in person.

Rick Lowe, “Project Row Houses: If Artists Are Creative Why Can’t They Create Solutions,” 2021, acrylic and paper collage on canvas, sixteen panels, 36 × 48 in. each, 144 × 192 in. overall (91.4 × 121.9 cm each, 370 × 490 cm overall). Collection of the artist; courtesy the artist and Gagosian, New York, Los Angeles, Paris, London, and Hong Kong

It has been a long two-plus years. The artists know it, and the viewer knows it: a game of dominos and a game of survival. Light and beauty thrown in for good measure.

I keep returning to Alfredo Jaar’s 06.01.2020 18.39 (2022), first during my Biennial visit, and now, weeks later, in my mind. Jaar’s installation, located on the sixth floor, is a black box theater containing a video from the protest in Washington D.C.’s Lafayette Square six days after George Floyd was killed. Then-Attorney General Bill Barr ordered the area to be cleared that evening while President Trump took part in an outdoor photo op at a nearby church. The black-and-white footage shows protesters and police clashing in a haze of tear gas and stun grenades; the sound stops momentarily and we are watching the silent film of our times. Two low-flying military helicopters appear on the screen and powerful turbines kick up overhead in the theater, physicalizing the force of their rotors, our leaders, the anger spinning this planet faster and faster. Jaar, who was born in Santiago, Chile in 1956, has said that the events of June 1, 2020, made him realize that “fascism had arrived in the USA.”

Two thousand miles from the Whitney Museum of American Art, in Far West Texas, I am sifting through some items at a small shop in Terlingua. The owner, an older man who hasn’t budged from his chair, asks me where I am from and what I do. He says he runs a local militia, and that most residents in town are armed to the teeth. The feds won’t be able to overtake us when the time comes, he assures me.

Installation view of Whitney Biennial 2022: “Quiet as It’s Kept” (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, April 6- September 5, 2022). Lisa Alvarado, a selection from the series Vibratory Cartography: Nepantla, 2021-22. Photograph by Ron Amstutz

I am thinking of that man in Terlingua as I contemplate Pinochet’s Chile in New York; of the World Trade Center, a few blocks south of the Whitney, and our slow slide into an illiberal abyss since 9/11; of the storm in 2012 that turned Chelsea into Venice, and all the storms since; and the black ferris wheel in the Biennial, constructed out of prison tables, turning like a heavy gear. The pandemic, the planet, darkness, and light: open secrets and hidden truths. Quiet as it’s kept.

“Do you think we are currently in a battle for the soul of America?” I ask the shop owner in Terlingua.

His answer comes as no surprise. It’s the same as mine, but for different reasons.

“Absolutely.”

The Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept runs through September 5, 2022 at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City.

2 comments

Thank you for this excellent review of the Biennial 2022!

Wow. Wonderful review of the Biennial. Absolutely moving.