Jeanine Michna-Bales, Majestic Theater, Reno, Nevada 2019. Part of the series “Standing Together: Photographs of Inez Milholland’s Final Campaign for Woman’s Suffrage”, 2016 – 2020.

I first met Jeanine Michna-Bales in 2017, in conjunction with her exhibition and book publication of Through Darkness to Light: Photographs Along the Underground Railroad, and had the pleasure of interviewing her for Glasstire. Michna-Bales’ process is very research-intensive, and her current project, Standing Together: Inez Milholland’s Final Campaign for Women’s Suffrage, is no exception. Originally scheduled for exhibition in 2020, to coincide with the 100-year anniversary of (some) women’s right to vote, the show was postponed due to the pandemic. Her stunning photographs combined with the essays and text from the book provide a personal foray into one women’s remarkable journey.

The show runs through November 13 at PDNB Gallery in Dallas, and there is a gallery artist talk this Saturday, September 18, at 2 pm. (Go here to rsvp.)

Colette Copeland: I read that your initial inspiration for this project came from digging through file folders of the Women’s Franchise League of Indiana while visiting family in Indianapolis, as well as the desire to visually document the century- long struggle of the American Women’s Suffrage Movement — a history that is often left out of text books.

As with your former project on the Underground Railroad, this project required extensive research before beginning the photographic component. While the Underground Railroad project focused primarily on the landscape and place to tell the visual story, this project follows one particular suffragist — Inez Milholland and her 1916 Western campaign to generate support for the female vote in the Eastern states. In Standing Together, the landscape is still prominent, but you also include some photographic re-enactments of Milholland and other suffragists, interspersed with newspaper accounts and quotes from Inez’ letters to her husband. Tell us about your decision to include artifacts, portrait re-enactments, as well as the archival research within the project.

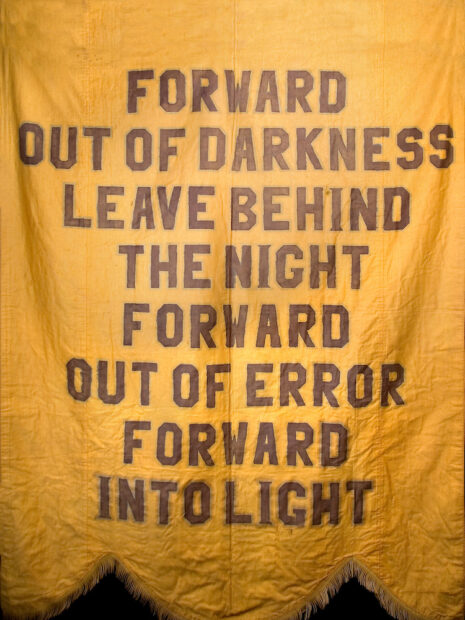

JMB: As mentioned above in your question, my previous body of work was entitled Through Darkness to Light: Photographs Along the Underground Railroad (2002 – 2016). While doing research for that book, I came across the beginnings of the women’s rights movement when two American women were banned from attending an Anti-Slavery conference in England because they were female. I started to research women and was looking for a way to enter into a century-long fight that encompassed thousands of locations, women and people. How could I personalize this movement and gain a visually interesting entrance into it in order to tell the story of the struggle for women to win the right to vote in our country? I stumbled across a banner carried by suffragist Inez Milholland in a 1910 New York City suffrage parade. The first and last lines read, “Forward out of Darkness … Forward into Light.” I took this as a sign from the Universe that Inez Milholland and her story would become the entry into the movement I had been searching for.

The suffrage story along with Inez and other women from her time tell a complicated history of how women are viewed and what is expected, or rather not expected, of them. These views still shape how women and their various roles are viewed today. The artifacts, portrait re-enactments, as well as the extensive archival research (most of which remains behind the scenes) exist to help tell the story in as much detail as possible. I think understanding Inez and her motivations, her failures, her sheer determination and will help humanize their struggles. And we can see that their struggles are still our struggles today.

Jeanine Michna-Bales, Arsenic and Strychnine. The Sunset Club, Seattle, Washington, 2018. Part of the series “Standing Together: Photographs of Inez Milholland’s Final Campaign for Woman’s Suffrage”, 2016 – 2020.

CC: How did you select the people for the photographs, since you were traveling extensively throughout the Western States? Where did you find the artifacts, like the railroad spike, the ballot box, and the bottle of arsenic/strychnine? And the period costumes?

JMB: Since Inez and her fellow suffragists, ultimately, gave all women the right to vote — although sadly in some states it would take until 1962 for Indigenous women and 1965 for women of color – I wanted to have reenactors from all walks of life stand in for Inez and her fellow suffragists. I asked friends and colleagues to stand in for Inez for local photographic shoots. And I also contacted local branches of the League of Women Voters and AAUW (American Association of University Women) to ask if they would be willing to send out queries about participating to their local member base. This worked well in Chicago and here in Dallas as well. I was also lucky enough to have a dear friend travel with me on a week-long excursion from Salt Lake City and Ogden, Utah to Nevada and California.

Artifacts were found in various locations. I found the railroad spike beside the railroad traffics high up in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The ballot box was found in the archives of the Indiana Historical Society. And frighteningly enough, the bottle of chocolate covered arsenic and strychnine pills was bought on ebay. We have collected antique bottles for years now, so the other bottles are from our personal collection. The crown (“Star of Hope”) was recreated from a 1913 parade image of Inez by Iron Age Studios here in Dallas. And the photos of Inez and her sister Vida were created from digital files from the Library of Congress that I digitally put into antique photo frames that we have here in our 1911 Prairie Style home.

Jeanine Michna-Bales, Resting. 2018. Part of the series “Standing Together: Photographs of Inez Milholland’s Final Campaign for Woman’s Suffrage”, 2016 – 2020.

The “period” costumes were all purchased online from various vendors. I needed to have items in all sizes because I never knew who would be wearing them very far advance. So, I opted for pre-made items. The dress for instance had a tie at the back that could be tied tighter or looser depending upon the size of the reenactor. I referenced advertisements in the newspapers and magazines from the time period to determine styles, including hair styles and makeup.

Jeanine Michna-Bales, Whistlestop Speech. Cut Bank, Montana, 2018. Part of the series “Standing Together: Photographs Along Inez Milholland’s Final Campaign for Woman’s Suffrage”, 2016 – 2020.

CC: One of the strengths of the project and book is how you navigate between the personal story of Milholland and the larger history of the suffragist movement. I could imagine myself on her journey — riding the train with her grueling travel schedule, yet committed to daily public speeches and events, despite a lack of sleep and poor health. The project collapses time as we see majestic landscapes, as she might have seen through her train window, yet now through your contemporary lens (and in color). More personal moments such as the staged image of Milholland resting, the arsenic/strychnine bottle and her hand titled Life Line suggest her personal struggles and sacrifices.

Jeanine Michna-Bales, Contemplating a Family. Outside of Salt Lake City, Utah, 2018. Part of the series “Standing Together: Inez Milholland’s Final Campaign for Women’s Suffrage”, 2016-2020.

It’s also interesting to see images of hotels, theaters and train stations that are still standing today. The text and imagery bring Milholland’s story alive, while allowing the viewers to invest in the significance of suffragist history. Feminists are negatively stereotyped (typically from the conservative patriarchy) as radical, man-hating, and anti-family. The project deconstructs those notions. Some of the most touching parts of the book for me were to learn that Milholland very much wanted children, her husband was a staunch supporter of her career, their relationship was egalitarian, and they shared a great love and mutual respect — which was cut short by her untimely death at age 30, due to doctors who poisoned her.

JMB: I think the entire project is to humanize women and to let us understand that many of the struggles that we still confront today, they were just as strongly fighting in the past. Things as simple as who does the domestic chores that we still struggle with today. Especially working women. And stereotypes of women’s roles and their place in society. Back then, women were literally property of their husbands and had even less rights than their children. Colonialism and its views of women’s roles are hardwired into our societal norms, coded into our laws, and taught to the next generation. In some respects, we have come a long way in a 100 years and in many others we still have a long way to go. My Mom was fired from her job when she got pregnant with my sister in 1965. The Pregnancy Protection Act did not pass until 1978. Credit cards couldn’t be issued in a woman’s name unless there was a male cosigner in the 1970s. And up until 1992 a woman who owned a small business could not get a SBA (Small Business Association) loan without a male cosigner, as well. Pharmaceutical drug tests were solely done on men until the 1990s. Women’s rights, gender rights, civil rights and voting rights are all equally important and are all inextricably intertwined.

CC: As I read Linda J. Lumsden’s introduction and your essay Forward Together in the book, I was surprised to learn that in the 1700s Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York and New Jersey did not have gender restrictions on voting, and New Jersey did not have racial restrictions. And then in 1777, states began to revoke voting rights based on gender and race. It was seventy-four years after Milholland’s epic trip and subsequent death that white women’s right to vote was ratified in August 1920. The historic suffrage movement did not include women of color. It was another four decades before Indigenous women and Black women could legally vote — 1962 and 1965, respectively.

As you mention in your essay, we still have a lot of work to do in the areas of gender and racial equality and justice. We’ve seen Roe vs. Wade revoked in multiple states including Texas, and racial violence continues nationwide. The title of the project and book Stand Together symbolizes a hopeful anthem, a call for unity and progress. How might Milholland’ activism resonate in today’s climate?

Moonrise. Virginia City, Nevada, 2018. Part of the series “Standing Together: Photographs of Inez Milholland’s Final Campaign for Woman’s Suffrage”, 2016 – 2020.

JMB: I think I started to address it in the previous question. Civil rights, gender rights and voting rights are linked. We as a country (in some states) started out in the right direction. But, then colonialism pulled us down the path of repression, entitlement, and ultimately white, male supremacy. We did go backward in the past by revoking people’s rights slowly and methodically. And we are standing on that slippery slope right now, looking over the edge.

We are currently in many states quite literally going backwards. The Supreme Court gutted one of the main components that protect people of color and their voting rights in 2013. Since then, we have seen state after state enact more restrictive voting laws. If voting is restricted, then the government does not truly represent the people. And if voting is restricted, what other rights will follow? We, unfortunately, are seeing this all happen in real time. And it is beyond alarming. How do we stop the slide?

I don’t know. I think being aware of the past, the mistakes of the past, the hard-fought wins of the past, gives us a different perspective on how we view our present day. Can we learn from past mistakes and make different choices? I honestly hope so. I hope for a more inclusive future. One where we find a way to navigate the “us versus them” mentality. Find a way to bridge the gap and bring people together in order to see the humanity in each and every one of us regardless of gender, skin color, ancestry, religious views, or any other unique aspect about us that seems to make us seem “different” from ourselves.

The show runs through November 13 at PDNB Gallery in Dallas, and there is a gallery artist talk this Saturday, September 18, at 2 pm. (Go here to rsvp.)

5 comments

This is an excellent, informative show, well worth seeing.

Thank you Scott. Glad you both made it to the opening.

Jeanine Michna-Bales, your project from the point of view of women’s suffrage is so touching and sweeps such a wide path of emotions via your images. How can I help? I’m a photographer in San Antonio. Thanks.

Thank you Emily Blase. We are actively looking for venues for the upcoming traveling exhibition of the series. If you have any suggestions, please forward.

I will – I may have an idea and will check it out