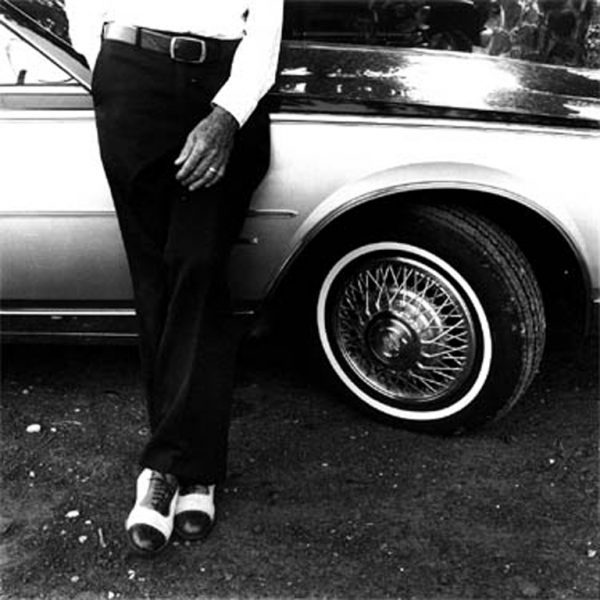

Keith Carter, Maydelle, Cherokee County, TX, 1985, Courtesy Keith Carter and PDNB Gallery, Dallas, TX

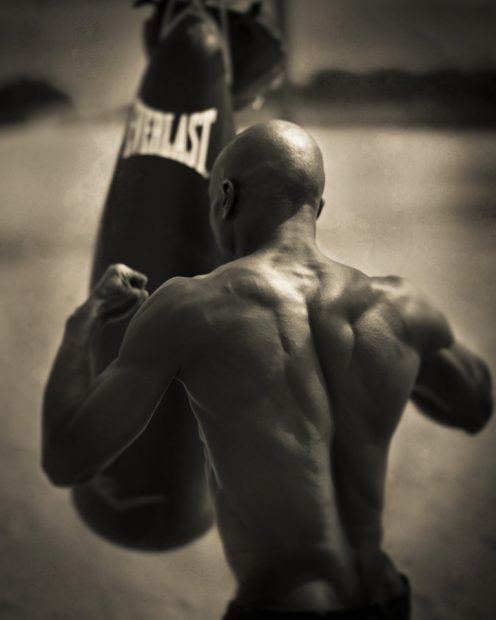

Keith Carter has enjoyed a long and distinguished career that makes it surprising for some that he resides in Beaumont, a small town in southeast Texas. While his hometown may be small, Carter’s vision is large and nuanced. This year, Carter is celebrating 50 years as an image maker with the release of a large tome published by University of Texas Press, Keith Carter: Fifty Years. Designed by D.J. Stout in conjunction with Pentagram, the book signals another rite of passage for the artist.

And while I am on the topic, isn’t it interesting that photography is often only mentioned as an addendum when it comes to written material? “Art and photography”, i.e. Art and photography, as it is often phrased, do not occupy disparate terrain — and if you doubt this, view the book’s accompanying exhibition at PDNB Gallery in Dallas. You’ll find plenty of luminous proof there.

In fact, Carter’s work is included in a list of institutions and collections that is staggering by anyone’s measure, among them the National Portrait Gallery, the National Gallery of Art, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum in D.C.; the Getty Museum in L.A; The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; The Art Institute of Chicago; President and Mrs. Barack Obama; President and Mrs. George W. Bush; Yale University Museum; Harvard University; and of course, right here at the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth.

I interviewed him on the occasion of the book release and the show at PDNB.

Patricia Mora: Can you speak of your term, “small epiphanies”? It seems as if they occur both during the capturing of an image and afterwards — during the phase when the image emerges as a new, sometimes surprising, entity.

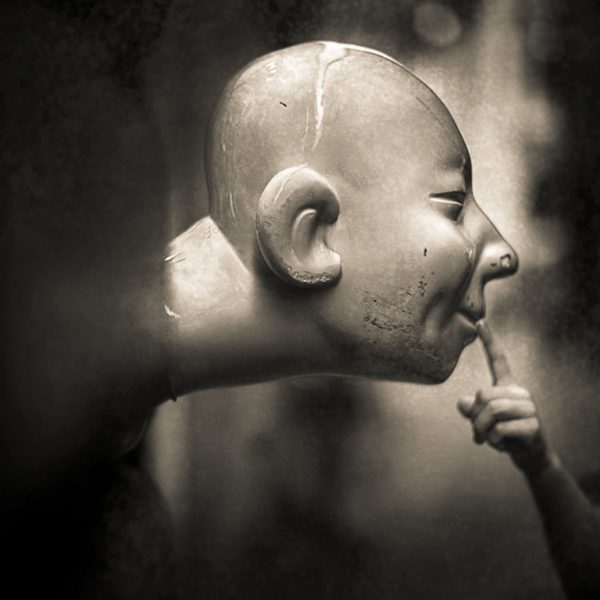

Keith Carter: I tend to work in the real world where actual events take place, rather than stage or conceptualize events. Occasionally, ordinary moments can seem transcendent to me. They tend to be alive with multiple meanings. They are what I call “small epiphanies.” For instance, I photographed a lost dog. It was a close-up, tightly composed portrait where I was focused on the eyes — which in turn, looked anthropomorphic, like the eyes of people I’ve known.

Mora: Can you characterize the nature of epiphany in the role of art generally? Does the degree of epiphany, so to speak, coincide with the image’s capacity to endure?

Carter: I suppose for me, epiphanies are how discoveries are made. They tend to move us outside of our own, occasionally limited, perspectives to consider new possibilities, and hopefully higher truths. I suppose the degree of epiphany, so to speak, coincides with the images’ capacity to endure because of their capacity to surprise and inform us. They can often lead to additional discoveries.

Mora: Your photographs of animals, particularly dogs, seem to transcend bifurcations of the real and transcendent. Are these disparate or overlapping realms?

Carter: For me they are overlapping. Years ago, I read a wonderful book by J. Mason Brewer called Dog Ghosts and the Word on the Brazos. It was a collection of African-American folk tales found in the rural areas of East Texas. The stories were originally rooted in Central African mythology where the basic theme was that if a loved one died, and you were in time of need, the spirit of the loved one, in the form of a dog, could return to help or protect you. I was electrified. For me, it opened up possibilities in mundane, democratic subject matter found all around me.

Mora: “No Rules.” Tell us more about your theory of this adage.

Carter: I think “rules” in art-making is a pejorative term. It tends to stop possibilities dead in their tracks.

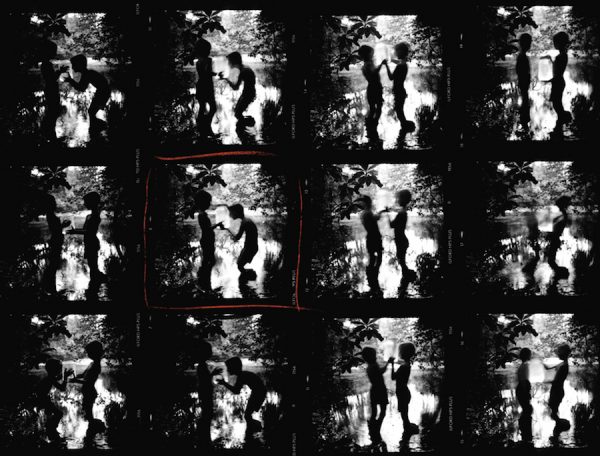

Mora: The Fireflies images seem to be emblematic of your manner of working and your imaginative trajectory. Can you tell us more?

Carter: Fireflies was originally a mistake — a failure in my mind. I had meant to make a sharp image of the two young boys standing in a pond at twilight, playing with the jar. But they were completely absorbed, paid no attention to me, and wouldn’t hold still. When I developed the film, I was completely disappointed. The only point of focus was the tip of a magnolia leaf — everything else was a motion blur. It was my wife, Pat, who came out to the darkroom and said I should print it. She is an extraordinarily thoughtful woman.

Mora: Muddiness is a kind of “theme” in southeast Texas. How does Beaumont operate as a genius loci and how does it influence your work? It almost seems to conjure a sense of magical realism — or at least not be inimical to it. As an aside, I will disclose I am from Port Arthur.

Carter: Where I live on the Louisiana border, it is a flat, tangled, green, and sub-tropical topography. There are no grand vistas. You tend to see things through other things. It was the playwright Horton Foote who helped me to see this no-man’s land with new eyes. I listened to him speak at the Galveston Opera House. He said he had found, after moving to New York to write, that he needed to “belong to a place, a place where I was rooted.” I was just flat-out electrified. It was what I call a “perfect moment” — the stars are aligned and the gods smile benignly. I started to photograph everything, including spaces in the air, in my largely forgotten, semi-rural culture. Now I travel widely, but I always take that same aesthetic with me. Everything is alive with possibilities.

Mora: How do you see the future of photography evolving? And your own work?

Carter: If you look at the history of photography, one process has always replaced another in its evolution. The irony is that none of them have ever disappeared. There is probably more interest in antiquarian processes than ever before. Photography has changed and will continue to change. You can make the argument that it remains the most important graphic medium of our time. In my own individual art practice, I tend to use everything available, from wet-plate collodion to digital media. No rules.

As for me, the work continues to change as I change. I think of my photographs loosely as autobiography. They’re a ragged record of my time on earth.

Through May 4, 2019 at PDNB Gallery, Dallas