Manik Raj Nakra is an artist living and working in Austin. He was an artist-in-residence for the 2020 LINE Residency sponsored by Big Medium at the LINE Hotel in Austin, and also participated in the Crit Group program at the Contemporary Austin in 2019. After a seven-month postponement due to the pandemic, Nakra’s solo exhibition W I L D L I F E is on view at Big Medium until May 1.

In conversation with Caroline Frost, Nakra describes how his work reflects on feelings of isolation during the past year, the rebirth of the natural world, and mistakes of the past.

Caroline Frost: You participated in the LINE Residency last year. What was that experience like during the pandemic?

Manik Raj Nakra: The LINE Residency was my first ever residency. It was during the first half of this ongoing pandemic, so the hotel was pretty empty. It also came about at a time when I had hit a creative wall. I had artist’s block. Living in a hotel, being paid for two months, given the freedom to fuck up and hate my work, and swim in the swank pool while nobody was around was liberating. Twice a week I would just take a projector down into the lobby and project weird vampire flicks, vintage nature docs, and silent films and sit on the floor and paint. Every once in a while, you have to get a volume of bad work out of your system as an artist. I learned a lot about how I wanted to advance my painting skills in those failed artworks as I move forward. I treated the residency as a laboratory rather than a studio pumping out work.

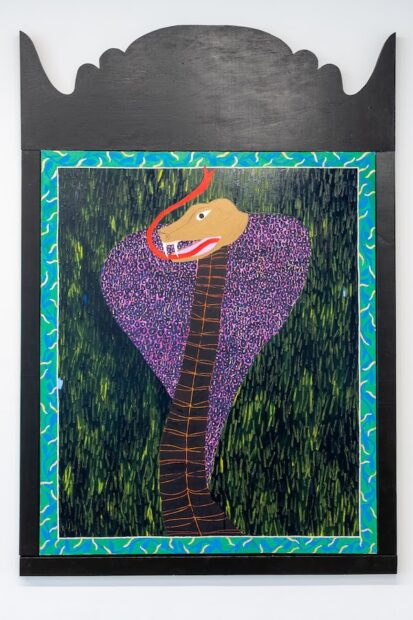

Manik Raj Nakra, D R E A M, 2020. Oil paint, acrylic paint, patina-ed gold leaf, ceremonial bindis, collage on canvas and wood, 83 x 71 in.

CF: Were you working on a different body of work before the pandemic?

MRN: I was working on a series off and on for the past two years that I call vampire paintings, in which I was recreating scenes from vampire flicks, but with my own visual vocabulary. So, in my works, the tiger and other animals were the vampires. These pieces are about influence and immortality, lust and imperialism, and how they’re all intertwined. But as I worked on the vampire paintings for about two years, I was kind of in cruise control a little bit. There are still more ideas that I want to pursue and it’s kind of a deep well. There’s just a lot to talk about with vampires and a lot of cool art, and vampires are just sexy.

But I wanted to do something fresh for Big Medium because they’ve always been so encouraging of me to experiment. They’re kind of like that with all the shows they put together. That’s why a lot of Big Medium’s exhibitions, I feel, are more conceptual in nature and more experimental, rather than just straight-up 2D works on the wall. So I was really surprised that they even offered me a show. I wanted to do something fresh and experiment a little bit. I decided to pause on the vampire paintings for now. I’ll maybe let that marinate a little bit and come back to it again to finish off the ideas that I still have remaining with them, after getting some distance, to see if ideas morph.

CF: You reference the media coverage of animals reentering their habitats when humans were in quarantine, like dolphins in the Venice canals, as a source of inspiration for WILDLIFE. Was there a specific moment when the conceptual basis for this show came to you?

MRN: Most people may not remember this, but in my opinion, spring of 2020, when the lockdown started, was the best weather that I’ve ever experienced in my two decades of living in Austin. It was in the low 70s during the day and low 60s at night, and it would rain just once a week to keep everything green and blooming. So, my daily routine was to have lunch outside under a tree in my backyard. I would lay down a blanket, sit under this tree and have lunch, and look up at the sky — and now I have these cloud drawings! So, the inspiration was a combination of just being outside and sitting, seeing everything growing, and also those headlines.

CF: You mentioned that self-sabotage, lust, immortality, and imperialism are intertwined. Can you expand on how that is?

MRN: I’m someone who is enamored with the ancient world, endlessly fascinated. Although I consider myself a contemporary artist, at the museums I always find myself drawn to the natural history and antiquities rooms. Sure, there is this brilliant Mark Bradford show in the other room, but look at this 2,500-year-old ivory comb that belonged to a pharaoh. It’s got a fable carved into it. Its half broken. Self-sabotage, lust, immortality, imperialism are common themes to all old-world civilizations, and because they’re in the past, we have the advantage of seeing how it played out.

CF: What is it about those three specific ideas — self-sabotage, lust, and immortality — that make them so influential in your work? How do they apply to this series?

MRN: There are a lot of severed animals heads in the show. All the heads are also depicted upside down to reference self-sabotage and the mistakes of the past, serving as a reminder as new life grows.

Thematically, this idea of self-sabotage, lust, and immortality are running themes in my work, and I always have those three shadows behind me in the studio, so that’s probably where I’m headed. But I would say these are probably the most hopeful paintings that I’ve ever made.

CF: Have you noticed a shift in your work with the pandemic as a turning point? Stylistically, thematically… ?

MRN: Stylistically, definitely. Between the vampire paintings and this show, I participated in Crit Group at the Contemporary Austin. Through that program I rediscovered oil paint. I started using oil paint simply because my favorite artist used it, and I just thought it looked more expensive.

I’ve never taken a formal art class in my life, except for 12th grade art, so I didn’t know the material. I just started using oil paint in a similar fashion to how I was using acrylic paint, and I’d been doing that since like 2007 or 2008. It was through that Crit Group program where I felt safe to start using oil paint as oil paint, and begin experimenting a lot more with blending and mixing other mediums in with it. Previously everything was super flat, and now there’s texture — I let the brushwork show; some of it is just glopped on there. So, I’ve just gotten more comfortable with working the canvas more instead of being tender with the brush.

CF: With WILDLIFE, it seems like an inversion has occurred in your work. Previously, you project the ancient world into a contemporary setting to examine these overarching themes of the human experience, such as lust and self-sabotage. In this series, you’re taking a very specific contemporary moment and casting it backward into this ancient framework that is pre-Anthropocene.

MRN: I typically don’t paint from real life. Real life might seep in subconsciously, but I don’t actively do so. This I think is the first time I’ve painted from real life, but I think that’s because this moment of isolation was so universal. The pandemic is probably the biggest world event in my lifetime, other than 9/11. I’d been offered this show right as lockdown hit, so it’d be idiotic not to reference Covid, the pandemic, lockdown, or something. In one way I felt obligated to reference what’s happening in real life, and in my own life, but I think I was still able to broaden it up to make it a more universal experience.

CF: It doesn’t translate as everyday subject matter; it’s still very fantastical. And there’s this overlying theme of mythology and folklore. Do you think that mythology is necessary to grapple with unprecedented events, change, newness, a genesis of a new world?

MRN: Yeah, I think so. I read that we only use 10% of our brain, so that 90% is doing something and we don’t even know what yet. I think something like the pandemic, or even just the way that the Earth moves, is so fantastical that we have to find some purpose in it, and that’s where the mythologies come in. It’s just really interesting that if you go back through human history, and look at all these ancient civilizations that span thousands of years from every corner of the globe, there’s so many commonalities between all of them. For example, almost every culture has a Sun God. I have this work in WILDLIFE titled Moth because while I was researching death, I found that moths were popping up as allegories for angels of death in cultures all over the world; Asia, South America, Africa have all depicted moths as angels of death. In Moth, death is leaving the Tiger’s mouth so that new life can spring.

Manik Raj Nakra, M O T H, 2020. Oil paint, ceremonial bindis, collage on canvas and wood, 98 x 67 in.

CF: I’m glad you mention this work, Moth, because I think it’s such a great representation of how ancient mythologies and folklores merge with pop culture — when I first saw that work, I immediately thought of Silence of the Lambs.

MRN: Oh yeah, I actually have that same moth in the show on the King of Delhi wall. The moth that is in that film is called death’s-head moth, and the pattern on its back roughly looks like a skull, so I just drew a literal skull on it. But it is a real species of moth.

CF: Is this your first time using vintage Japanese rice paper?

MRN: Yeah, it is. I’ve used a lot of handmade paper in the past. I don’t have the facilities or time to make the paper myself, but I really love handmade paper and I’ve been ordering it for a while through this Instagram account. So, one day they posted that they had a stack of this vintage Japanese rice paper, which is actually designed for block printing. I had no idea what the feel of it would be; I just ordered it, and I really fell in love with it. It’s so delicate. Some of these tears and things are just from me drawing on it too hard or rubbing a hole through it with an eraser. Because the paper itself is so delicate, I wanted to use really delicate materials to draw on it, so the most delicate materials I could find were charcoal, chalk, some pencil and pastels — but mainly charcoal and chalk.

CF: How is King of Delhi functioning in relationship to the five larger paintings?

MRN: The King of Delhi installation is my ode to Mughal architecture. If the five eight-foot paintings are the windows of the mystical palace, King of Delhi is the palace. It’s a castle in the clouds. I wanted to give it this Fortress-of-Solitude quality which is why the cloud drawings hang freely above the viewer’s head, and there are lots of depictions of walls. The installation is made up of about 40 charcoal and chalk drawings on vintage rice paper. In addition, the drawings are arranged into the shape of a palace with a central dome and minarets on either side. And these watercolors are the wildlife lurking around the palace ground.

CF: Like an abandoned structure?

MRN: Yeah, like a fortified structure. So, things are overgrown a bit and there’s a presentation of what’s happening behind the walls. There are a lot of walls in this installation just to, again, reiterate this idea of isolation, because the show is less about Covid and more so about isolation.

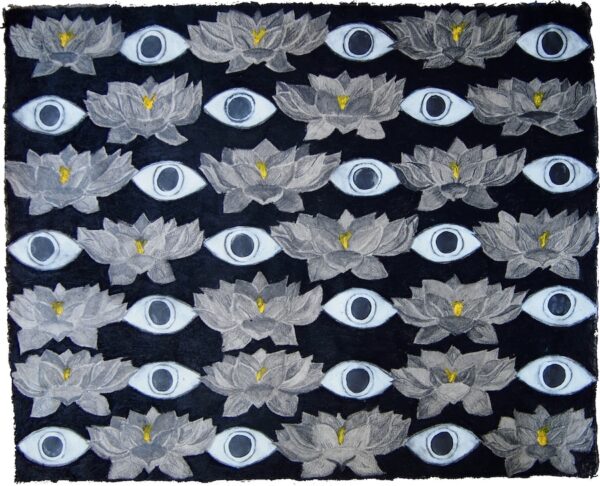

Manik Raj Nakra, LOTUS EYES, 2020. Charcoal, graphite, oil pastel on vintage japanese rice paper, 17 x 20.5 in.

CF: How do the religious and cultural themes in the show service this underlying theme of isolation?

MRN: With bindis all over the work functioning as third eyes, the paintings look back at you to give this existential feel. People tend to get very existential and spiritual while in isolation.

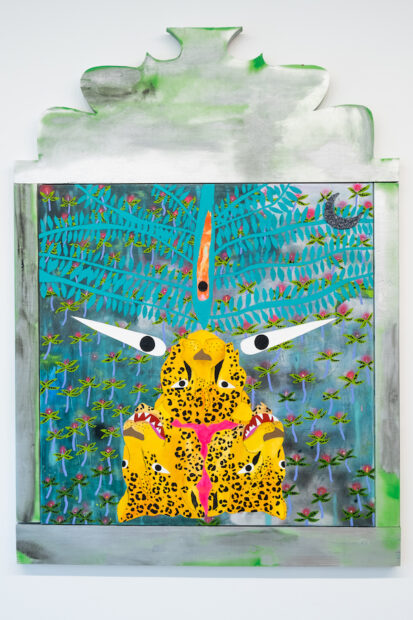

Manik Raj Nakra, S H I V A, 2021. Oil paint, acrylic paint, spray paint, metallic pigment, burlap, glitter, ceremonial bindis on canvas and wood, 74 x 53 in.

CF: The bindis invert this inside-looking-out into a way for the viewer to look inward from the outside. Simultaneously, they are functioning to anthropomorphize the flora and fauna by giving them a third eye to represent this inversion. How is the substitution of humans by anthropomorphized animals functioning to reflect on the mistakes of human invasion?

MRN: It’s funny you mention human invasion — imperialism and imperialist forces invading land is a running theme. Those armies had a crest or a coat of arms, and there’s a lot of jungle cats on them, so when I depict jungle cats, a lot of times those are metaphors for imperialism and colonization.

That’s why the heads in all the paintings are upside down, to represent the mistakes of the past. The bindis that I chose to adorn all the animals and plants [with] are not just the felt dots, which are of the older generation. These are more ornamental — they have little gemstones in them. The twinkling gemstones are the remnants of the past, to reflect on past mistakes. So, as new life grows, it still carries its past. There is a bit of an existential feel about it in that sense. Maybe we are doomed to self-sabotage with this plight of history repeating itself. But it’s up to the viewer to take it in.

Manik Raj Nakra’s ‘WIlDLIFE’ is on view at Big Medium, Austin, through May 1, 2021. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.