Rio Grande Valley-based artist Mario Perez’s solo show DIY at Houston’s Devin Borden Gallery features the artists’s chief characteristics: humor and reference to tradition. Behind it all, there is a view of the future.

The paintings are smaller in scale, with the largest at 20” x 26”. The subjects feature various cuts of meat, which Perez calls, in a 2017 McNay talk, “my little meat paintings,” as well as shoes, woodworking tools and gardening implements. Perez’s work draws from the Mexican and US-Mexico borderlands tradition of hand-painted signage on businesses, known as rótulismo.

Perez’s interest in rótulos goes back to his childhood. Living along the border and traveling in Mexico on family vacations, he saw many of the hand-painted mural signs that advertise a store’s wares — tools, jewelry and electronics for pawn shops, pineapples and watermelons for fruiterías. Main drags in the Valley and in parts of towns all across Texas feature these signs. While the skill in execution varies from store to store, they are, en masse, visually appealing. Abstracted from the street and painted on canvas, their depictions of food, clothing, and home goods make for implicitly witty subjects. DIY has examples of all three, progressing in complexity.

Perez’s meat series, which features different cuts of meat and accompanying script, directly address advertising tradition. While Perez mentions signs for meat markets in Mexico City in a 2019 interview, I see also visual reference to grocery store advertising inserts in newspapers, with photos of cuts of meat displayed along with their prices. In the show, this series is the most obviously funny, with the script on the paintings bearing messages like “Farewell” and “The End,” underscoring the ephemerality of butchered meat.

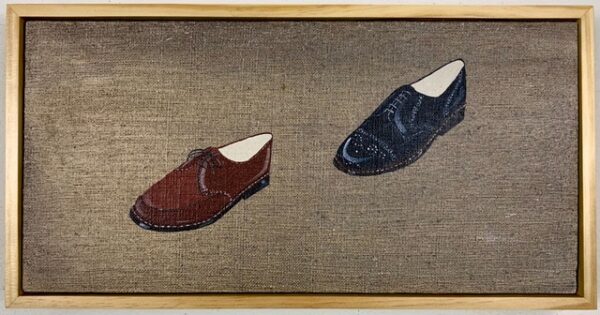

Another series focuses on men’s and women’s shoes, recalling signs for zapaterías and shoe repair shops. One example is of two men’s shoes — fancy leather shoes, the black pair perforated, rendered with little shading. Awkwardly situated on the canvas, with a sly twist, they are both left-footed. Whereas the meat paintings have flat black or white backgrounds, here, the texture of the canvas is enhanced; it looks as if Perez uses shoe polish on the canvas and subsequently wipes it off. The negative space dominates the painting. Perez’s interests begin asserting themselves.

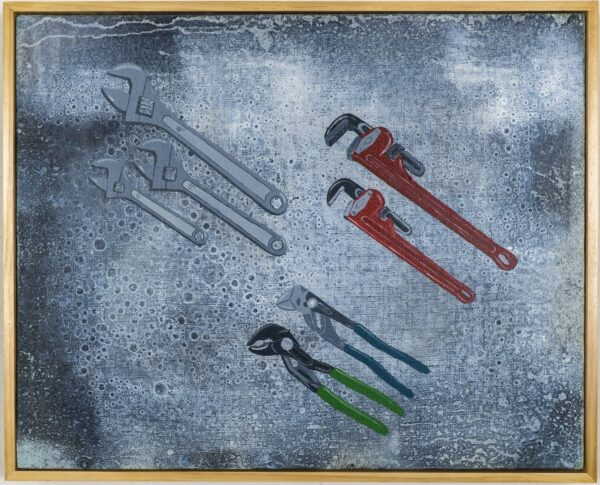

This trend is clearest in the larger series of paintings featuring what Perez describes as “priority tools” — fundamental tools people use for their jobs. It’s in these paintings that Perez’s subjects are totally decontextualized from the rótulo tradition, and the backgrounds emerge as the true subjects.

Don’t get me wrong: the wrenches, saws, axes, and rakes are cheerfully and faithfully appropriative of the rótulo style, and meticulously rendered. But in these larger works, the backgrounds have more space to show Perez’s skill of creating different effects through washes. One background might look like galvanized steel, another like corroded, and subsequently cleaned, tin. Still others abandon the metallic motif and instead look ethereal. The tools float on top of the washes and the effect is surreal, dreamy, and funny all at once — Twin Peaks goes to Home Depot.

Perez told me in our most recent phone interview, where he was taking a break from building a free-standing porch in his backyard, that he would like to move away from representational work altogether; he mentions Dorothy Hood and Mark Rothko often. With some larger canvases he’s already prepared, he plans to push forward into the wash: “What I’ve always done on canvas is a background and a foreground. Everybody pays attention to the front, but I eventually want to paint unrecognizable things. I’ll just keep painting things but slowly start losing them.”

After “losing” the things — the meat, the shoes, the tools — Perez can more fully embrace spaciality in the washes. But he’ll stick to DIY for the present. I ask if he will be using any of the tools he painted in building his porch. He pauses, laughs, and then says, “The broom, definitely!”

Extended through Jan. 23 at Devin Borden Gallery, Houston.