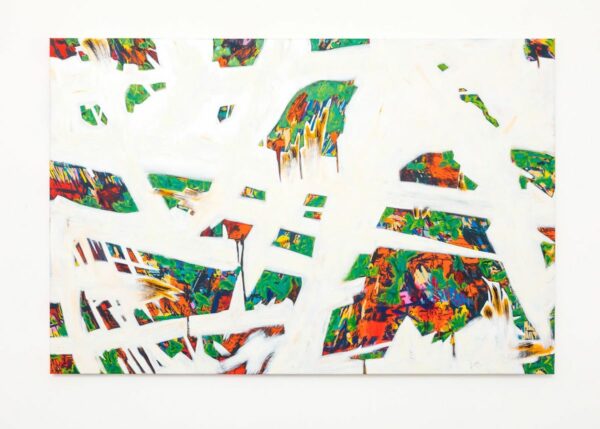

Installation view, Ruben Nieto: Cartouche at Cris Worley Fine Arts, Dallas, November 21, 2020 – January 2, 2021.

Ruben Nieto devoured comics and cartoons in his youth. In his native Mexico, his youthful eyes feasted on Spiderman, the Flintstones, Mighty Mouse, and other vittles. When Nieto plunged into art school, he gobbled down Picasso, Diego Rivera, and Reubens — and the whole horse of the Western art canon.

If you snake your way into Cris Worley‘s gallery in Dallas this month, you’ll soon hit the center space where Nieto’s 6-painting Cartouche show is hung. A 180-degree left turn there will put you face to face with Daffy. Like “Duck,” of course. Leaving aside the cartoon reference for now, what’s Nieto fooling around with here?

Over a field of protoplasmic color dominated by greens and oranges in potent play, Nieto has wiped out huge passages of the painting with a reckless brush — using fat, sweeping lines like Franz Kline (1910 – 1962). But where Kline dropped black over empty fields of white, Nieto drops white over pre-existing imagery — pulling off a feisty act of self-sacrifice. It’s a bit like the accursed rush that the crazed Hungarian, Laszlo Toth, took at Michelangelo’s Pieta with a hammer in 1972, or Robert Rauschenberg’s fevered elimination of the marks of an Abstract Expressionist great in his 1953 Erased de Kooning.

True to his starting point — the image of Daffy Duck — Nieto is fantastically free in pushing that cartoon through untold sieves of interpretation (he tells me) until the visual source-text becomes pretty much unrecognizable. We end up with a canvas where Daffy is chopped and chiseled and re-formed, somewhat like the old Norse giant, Ymir, was by Odin, who whistled while he worked:

Out of Ymir’s flesh was fashioned the earth,

And the ocean out of his blood;

Of his bones the hills, of his hair the trees,

Of his skull the heavens high.

Earth the gods from his eyebrows made,

And set for the sons of men;

And out of his brain the baleful clouds

They made to move on high

(Odin-talk in The Grímnismál, c. 1250)

Of course, Daffy sits in a kitschier pantheon, but his sacrificial body makes up this painting’s visual cosmos. If we look at what’s unslashed by the thundering swordplay of white, bits of how the duck’s ur-animator (Bob Clampett’s) color fields and lines can be identified in the painting’s now-socially-distanced blots of compacted color.

This process — a naked chopping-up of comic characters with bone-smashing white or a covert shattering of them into graphic shrapnel (more madly Picasso-esque than anything the master ever did with cubes) — is Nieto’s painterly method. It is aggressive. It destroys before (and after) it creates. In the spirit of both Lazlo Toth and the Vatican curators who patched up his mess, Nieto makes liberal use of both visual hammer and visual glue.

Daffy gives us the most vigorous lesson in this approach, but like a beer-fueled dad tearing through a teenager’s comic stacks, Nieto is hard at work slashing, re-imagining, and re-composing the cartoon companions of his youth in other paintings, too.

Unexpectedly, in his Snow White it’s not Odin’s icy snows that obliterate the helpless image in the pic’s backfield, but heaven-sent blues, which wig and wag across the canvas in torrents of mud-thick ultramarine, azure, and navy.

These big cold shapes don’t call Kline to mind. They look more like whipsaws from two of Kline’s big-ass, Ab Ex fellow travelers: Morris Louis and Clyfford Still.

Again, it’s just crazy what Nieto’s achieved in the backgrounds he dares to destroy. Peer close. It seems you’re looking at a cross-hatch paper shredder whose cache tipped over on a parquet floor, but it’s infinitely more exact than that! Nieto’s use of color and line via glitter-storm speaks assuredly of the comic book’s line and hue. It’s as if he’s worked with this cartoon imagery for so long that it swims without effort from his brush, no matter what he paints. He’s done the stunning thing of fashioning complex abstraction from the cartoon idiom. He can render “comic-bookness” in any form — like Van Meegeren effortlessly kicked out Vermeers. With the ruthlessness of any old Dutch master, he lays down comic memes with mechanistic consistency.

Maybe that’s what we should expect from a classically-trained painter who’s made a career out of mashing high art and low.

The Mexican navy called to Nieto when he was just 15, and he signed up with the intention to become a mechanical engineer — the metier of his dad. But the corruption he witnessed there was more than the idealistic youth could bear, so he quit, and set his sights elsewhere. His parents didn’t care if he just swept the streets, as long as he did it well.

In 1991, aged 19, he opted for architecture, joining other freshman at the Universidad de Guanajuato in south-central Mexico. But building design proved too constraining for an eye made wild by impressionable nights in the back of his parent’s car in the city of Coatzacoalcos, dazzled as he was by the new fashion of neon signage in the 1970s and the city’s other passionate colors. He tried graphic design next, but that proved limiting, too. Then he found his university’s School of Plastic Arts, where he could fiddle with fine art photography, sculpture, silkscreen, lithography, plate-printing, and painting. He leaped toward that broad curricula with a full heart. Painting quickly won his loyalty. In Guanajuato, he learned the methods of the old masters.

But his first art shows featured photography. Nieto aimed his lens at the brilliant wall-colors found in some Mexican houses — where cheap formulas of dense hues result from tempera-like powders mixed with plaster. The art tastes of children charmed him, too — he saw kids’ graffiti everywhere and was hell-bent on convincing his art history professor that the caves at Lascaux bore scrawls from both adults and children who were at play. Art priests weren’t ritualizing the hunt or elevating their animal-prey into gods, he suggested. His teacher admonished him when he floated the idea, but when he captured similar facts from nearby neighborhoods, she blinked, tacitly admitting that the young artist might be right.

Nieto’s first exhibition featured these pictures, and he took palette lessons from their tints and tones.

In Fred Flintstone after Picasso and Lichtenstein, Nieto’s color wheel is dominated by these stucco-cake colors. Hues of sandstone and carrot are set off by mottled Caribbean turquoise, and a dismembered figure in black and white is tossed over them like come-hither breadcrumbs. Color swooshes trample through the image, not working to blot it out this time, but as complementary graphic elements. They call to mind the showy vectors used to choreograph fists and feet in the violent worlds we know our cartoon characters spend all their days in. Nieto’s way of tearing comic characters to shreds isn’t as severe here as in Snow White or Daffy, so we learn something about the progress of his method. Flintstone’s signature hair floats decapitated in the air, rendered in both a black form and a white one. Hands and feet borrowed from Picasso’s Guernica (a violent, episodic, comic-book drama if there ever was one) are scattered around the picture, and Fred’s eyes turn backward beneath his hair — a contortion worthy of any Picasso, or of a flounder chopped and gutted on a boat dock.

Flintstone and the others in the show seem like way-stations en route to the more thorough abstractions of Snow White and Daffy. They reveal Nieto’s butcher-block method—rallying the spirits of history’s past masters to splice and dice the cartoon ghosts from his youth.

Through Jan 2, 2021 at Cris Worley Fine Arts, Dallas.