Taihu Rock, rear view with river and boat, SAMA. The rock is positioned on a separate rock base, and is affixed with steel and epoxy. Photograph by Ruben C. Cordova.

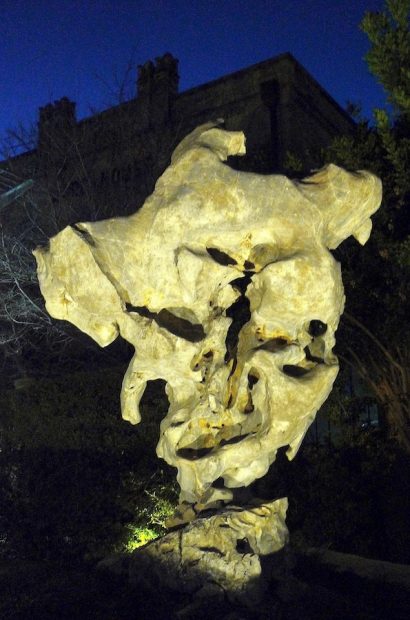

A twelve-feet high, six-and-one-half-ton rock from the shores of Lake Taihu has been gifted to the San Antonio Museum of Art (SAMA) by the city of Wuxi, which is a sister city of San Antonio in Southeastern China. Shawn Yuan, Assistant Curator of Asian Art at SAMA, first broached the idea of a gift rock when vice mayor Liu Xia of Wuxi (a city in the Yangtze River Delta close to Lake Taihu), visited SAMA during San Antonio’s Tricentennial celebration in 2018. Eroded rocks with fantastic forms have been revered in China for more than a millennium. Those from the Lake Taihu region are among the most highly prized. Fortunately, Liu is in charge of the cultural affairs of Wuxi, and she said yes.

In December of 2018, a SAMA delegation chose a Taihu Rock from several that had been designated as worthy gifts by Wuxi’s Garden Bureau specialists. That rock is now permanently installed on SAMA’s grounds, adjacent to the River Walk, evocative of the manner in which large garden rocks are traditionally placed in proximity to bodies of moving water. To commemorate this gift, the Wuxi Museum has loaned 26 pieces from its estimable collection — some of them of recognized national importance — for an exhibition called Elegant Pursuits: The Arts of China’s Educated Elite, 1400-1900, currently on view in SAMA’s Chinese galleries. Most of these works had never been outside of China before this exhibition. Yuan, who curated the exhibition, authored informative object labels. He also kindly answered many questions for this review.

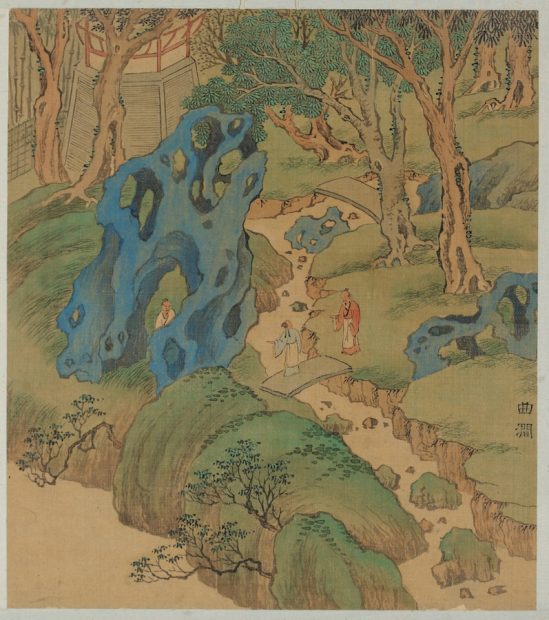

Song Maojin (died after 1625), Winding Brook, from Fifty Views of the Jichang Garden, Ming dynasty, early 17th century, album leaf, ink and colors on silk, 13” x 11”, collection of Wuxi Museum. Photograph courtesy of Wuxi Museum.

Nature is greatly esteemed in traditional Chinese culture. Consequently, as a Metropolitan Museum exhibition website notes, pitted, twisted, and perforated scholar’s rocks shaped (or seemingly shaped) by natural forces are especially highly valued in China, because they are understood as “embodiments of the dynamic transformational processes of nature.” These rocks are repositories of eons of natural forces: each one has been shaped and marked in a unique manner. Additionally, they are also “admired for their resemblance to mountains or caves, particularly the magical peaks and subterranean paradises (grotto-heavens) believed to be inhabited by immortal beings.” They are thus surrogate mountains and grottoes, whether they be small rocks in a scholar’s study, or enormous rocks in a magical garden with rolling hills and winding brooks, as in Song Maojin’s painting illustrated above. This painting features a rock so large and so completely pierced in its bottom center that a man can easily walk right through it. Additionally, various parts of the worn rock seem to suggest faces, a quality that is highly valued (as are rocks that resemble or evoke animals and other creatures). To the right of this large garden rock, on the other side of the simple bridge, a rock with a horizontal orientation seems to mimic the bridge. Finally, further back in the distance, a rock is situated in the brook itself, as if to illustrate the excruciatingly slow, natural process of erosion by water that creates these strangely beautiful forms. Yuan explains why the rocks are blue: “Painting rocks and mountains in blue is an artistic tradition that can be dated back to the 7th century. Blue pigment suggests the dense vegetation or moss-covered mountains and rocks.”

Song, an esteemed and well-known artist, made a series of paintings depicting the Jichang Garden, a famous and revered 16th century garden in Wuxi that is still popular today. This painting (one of ten on loan from this remarkable album) is a formidable representation of large, weathered rocks in a traditional Chinese garden setting. It is customary to have at least one body of water in these gardens. One could have a moving body, such as a river, stream, or brook; or one could have a still body such as a lake or pond — or even both kinds of water in the same garden. Since rocks are solid, heavy, immobile, and seemingly eternal, they make the greatest possible contrast with moving bodies of water, which are fluid, dynamic, constantly changing, and effectively lacking a fixed shape. These contrasts form a yin-yang pairing. Yuan adds that scholar’s rocks themselves constitute a yin-yang pairing, because of the inherent opposition between the solid and void forms that constitute them.

Taihu Rock contemplated by visitor, gray limestone with white veining and inclusions, 12 feet high, San Antonio Museum of Art. Gift of the Municipal People’s Government of Wuxi, China, in honor of the City of San Antonio’s Tricentennial Celebration. Photograph courtesy of SAMA.

Of the five or six large garden rocks evaluated by the SAMA delegation, made up of Yuan, Emily Sano, Senior Advisor for Asian Art, and Katie Luber, who was then SAMA’s Director, Yuan particularly liked the specimen they selected. He wanted this rock for several reasons: its large size (which makes it readily visible even from the other side the San Antonio River); its rare, inverted pyramidal configuration; the overall balance of shapes and voids; the abundance of holes large enough to look through; the rock’s extremely good state of preservation — it has no large breaks; and its pleasing, even, gray color.

Taihu Rock, view from the San Antonio River’s edge, SAMA. The museum is situated in the former Lone Star Brewery, whose “WARE-HOUSE” is in the background. Photograph by Ruben C. Cordova.

I visited the rock in the afternoon and evening, to capture it in differing lighting conditions.

Taihu Rock, side view from river, with one of the brewery’s towers in the background, SAMA. Photograph by Ruben C. Cordova.

Yuan estimates that the rock’s unique forms were shaped through interactions with water and sand over the course of thousands of years. He thinks it was probably quarried in recent decades. As noted on the Princeton University Art Museum’s website, scholar’s rocks, called gongshi (rare stones) or guaishi (fantastic stones) can also be “farmed” in the lake: they are drilled and deposited in the water, to be “harvested” much later, sometimes after the passage of centuries, when the water and sand have eroded them to a desirable state.

Taihu Rock, nocturnal view, with Pavilion building (not part of the original brewery complex), SAMA. Photograph by Ruben C. Cordova.

As noted above, mountains in Chinese culture are the enchanted abodes of the immortals. Additionally, the Confucian ideal led scholars to prefer a hermetic life in the beauty of nature, amid mountains, with pure air and water, far from mundane concerns. In these peaceful, spiritual settings, they would also contemplate beautiful works of art, write poetry, create extraordinary calligraphies and paintings, and make beautiful music. The large Taihu Rock is a way of bringing what the Princeton website calls “miniature cosmic mountains with heavenly grottoes and majestic peaks” to a garden setting, one that could be anywhere in the world — even in Texas.

Notable Taihu Rocks are in several important collections in the U.S., including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, and the Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California. SAMA’s large Taihu Rock is the first one in the collection of a Southern U.S. museum. It is also one of the largest in the country. Due to its unusual, top-heavy structure, it posed unusual challenges for the engineering firm tasked with mounting it on a stable base, which led the firm to consult with a dentist for technical expertise.

Ren Yi (1840-1895), Mi Fu Bowing to a Rock, 1886, 12” x 12”, collection of Wuxi Museum. Photograph by Ruben C. Cordova.

Ren Yi’s painting depicts Mi Fu (1052-1107), an illustrious poet, artist, and politician of the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127), as he kneels and bows, dressed in his formal robes and hat, before an extraordinary garden rock, which he addresses as “Elder Brother Rock.” I trust I am not alone in reading an anthropomorphic visage and limbs into Ren’s rendering of this beloved rock. Mi Fu bowing before his Brother Rock is a very popular motif — and not just in China. An Artnet article that discusses the gift of a suseok (the Korean term for a scholar’s rock) in Bong Joon-ho’s Oscar-winning movie Parasite also reproduces a famous painting of this motif by the Korean artist Hô Ryôn. Four criteria for evaluating rocks (both large and small) had developed by the Tang dynasty (618-907): shou (thinness), tou (openness), lou (perforations), and zhou (wrinkling).

The literati beheld scholar’s rocks with awe and reverence, for they symbolized the natural world and its material processes. They mastered Confucian principles because, like early European artists such as Fra Angelico, they believed high moral character was necessary to create truly spiritual art. Ren Yi was himself a very successful artist, with a large school and many admirers.

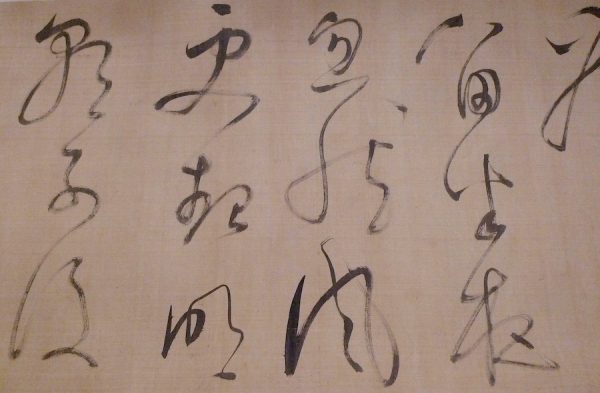

Dong Qichang (1555–1638), Calligraphy in the Style of Huai Su (737–799), Ming dynasty, 1611, Hand scroll, ink on silk, 12” x 225”, (detail), Wuxi Museum. Photograph by Ruben C. Cordova.

Deep and abiding respect for tradition is at the very heart of Chinese culture. Calligraphy has always been the most highly regarded form of visual expression. It requires lengthy training and study, including emulating the individual styles of acknowledged masters of previous eras. Dong Qichang was the leading theorist, calligrapher, painter, and collector of his age, and he remains highly regarded today. Here he transcribes poems in the style of Huai Su, who was another giant in the field. As Yuan notes in his label text: “the characters are deconstructed, abbreviated, and linked together to form a unified design… . The rapid flow of darting and looping brush movements required the artist’s intimate knowledge of each character and precise control of arm, wrist, hand, and brush … the characters’ legibility and the meanings of the poems recede to secondary status.”

Yuan explains why one doesn’t need to be able to read Chinese characters to appreciate calligraphy: “Chinese calligraphy is an art of forms. You don’t have to understand the language itself. The flow of brush stokes, the rhythmic alternation of dry and wet ink, and the balance of broad and thin lines make a fine calligraphy almost a piece of expressionist art. A viewer can sense the calligrapher’s inner world, even in a piece that was written hundreds of years ago.” Thus each of these characters can be appreciated as an independent figure, or as an expressionistic mark, somewhat akin to how Paul Klee characterized drawing as “simply a line going for a walk.” Of course, in the Chinese context, this “walking” is done within the bounds of a long tradition that is marked by reverent emulation and astonishing rigor as well as creative innovation. Dong’s flashy brilliance rewards close inspection of his handiwork. In Western art, one can make a parallel with some works by Jackson Pollock: when he was transitioning from figural art to abstraction, he sometimes blurred the lines between graphics and pictographics.

In this review I’m emphasizing rocks and the natural world, but I would be remiss to not mention Cheng Hongshou’s (1598–1652) Three Teachings of 1627, a painting of enormous importance that represents the sages of the three great teachings: Buddhism, Confucianism, and Daoism.

Ink Palette, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong period (1735–1796), porcelain, 1.3” x 3.8” x 4”, collection of Wuxi Museum. Photograph by Ruben C. Cordova.

Though not one of the “four treasures” of a scholar’s studio (brush, ink, paper, and inkstone), ink palettes, which were used to extract excess ink from a brush, were vital tools. This beautiful palette takes the form of a willow leaf, and its crackled glaze is an example of ge ware.

Miniature Mountain, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 19th century, malachite on wood base, 2.2” x 4.2” x 1.2”, collection of Wuxi Museum. Photograph by Ruben C. Cordova.

This miniature mountain is the kind of object routinely fashioned for scholar’s studios. Its green color symbolizes vegetation, and its indentations invoke grottos, with all the attendant symbolism. Additionally, the wood base depicts a fungus called lingzhi that confers immortality. Jade was such a revered material in Chinese culture that — prior to the Qing dynasty — malachite was deemed an unworthy material for such objects.

Chen studio, Stemmed Cup and Plate, Yuan dynasty (1279–1368), gilt silver, 2.5” x 7.1”, collection of Wuxi Museum. Photograph courtesy of Wuxi Museum.

The exhibition includes a pair of extraordinary “luxury” objects that would never have been associated with scholars or found in their studios. They are meant to highlight Wuxi’s material wealth. The Jiangnan region became prosperous during the Yuan dynasty, and curator Yuan points out that this wealth “supported the long literati tradition in this region.” The 1960 excavation of the tomb of Qian Yu (1247–1320), who was from a noble family, yielded many valuable objects, including this cup and plate of blossoming peonies, symbols of wealth and prosperity. The four characters on the underside of the plate translate as “Made by the Chen [family] studio.”

Hair Ornament, Ming dynasty (1368–1644), gold, 3.8” x 3” x 3.3”, collection of Wuxi Museum. Photograph courtesy of Wuxi Museum.

This gold hair ornament was designed to envelop a married noblewoman’s topknot on formal occasions. It would have been held in place by a pin, and worn in conjunction with other luxury ornaments made of precious materials. It is fabricated out of tightly knitted gold mesh and overlaid with gold wires. The latter divide the upper portion vertically into three sections. The curvilinear ornament represents a cloud puff, a lucky sign connected with immortality, and thus a good choice for a burial object. Noble tombs in the Jiangnan region have yielded similar works in gold and silver. Emperor Wanli’s (ruled 1572-1620) golden crown was also fashioned with techniques similar to the ones found in this hair ornament.

Jiang Rong (1919–2008), Teapot, mid-1950s, Yixing ware, 4.1” x 7.2” x 4.5”, collection of Wuxi Museum. Photograph courtesy of Wuxi Museum.

Elegant Pursuits also features more recent objects, none more striking than Jiang Rong’s diminutive and fantastical teapot, which he conjured wholly out of natural forms. The body is a lotus flower, with rhythmically ascending petals that are skillfully detailed and differentiated. They culminate in dramatic reddish tips. A wonderfully textured, curved lotus stem becomes the pot’s handle, and a cleverly folded leaf its spout. A lotus root, a water chestnut, and a water caltrop are rendered as the teapot’s feet.

The lid is a lotus pod — complete with rattling seeds — and the boldly colored frog that sits atop it serves as the handle. Who wouldn’t want to savor tea served from this charming incarnation of the natural world?

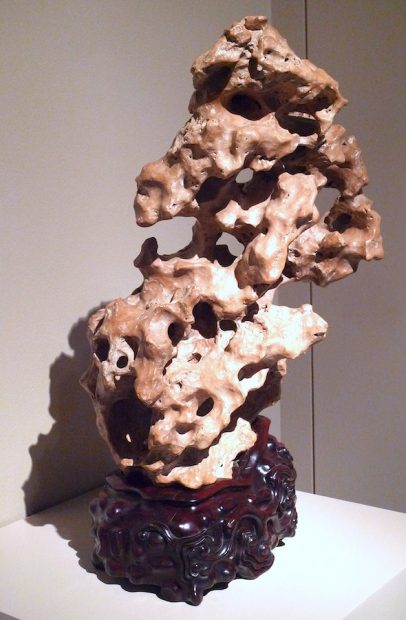

Scholar’s Rock, quarried 19th–20th century, off-white limestone with caramel markings and ivory inclusions, 30.5” x 17” x 10.5”, lent by Mr. and Mrs. John L. Hendry III, San Antonio. Photograph by Ruben C. Cordova.

This outstanding, small-scale rock (to fit in a scholar’s studio) is of a type quarried in Guangdong, in southern China, which is one of the other sites in China where rocks have been collected by literati for centuries. It has been polished, and much handled, as well. The complexity of its interwoven cavities is remarkable. Since it can be viewed advantageously from all angles, it is what connoisseurs call a “four-sided” rock.

Taihu Rock, from nearly a side view, facing the river, with jogger and dog, SAMA. Photograph by Ruben C. Cordova.

SAMA’s Taihu rock also looks distinctly different from different viewpoints.

Just after I had taken my final picture of SAMA’s new acquisition, a group of visitors approached. “How do you like the rock?” I inquired.

“We LOVE the rock,” they replied, almost in unison.

The Taihu Rock is on permanent display at the San Antonio Museum of Art. The “Elegant Pursuits” exhibition, which is accompanied by a brochure, has been extended without a fixed end date.

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian who loves rocks.

8 comments

Thank you for this good news of the permanent installation & for a glimpse of the temporary exhibition.

You are very welcome, Brian. The rock really has a presence.

Thank you Ruben Cordova for the informative article and beautiful photographs of the Taihu Rock now installed at the San Antonio Museum of Art. Even the photographs of the rock evoke a desire to look upon it and meditate; such a calming effect is especially needed now. I can’t wait to get out of quarantine and see it in person.

You are most welcome, Jo. I’m sure you will find the rock even more impressive in person.

You rock Ruben!

Rocks also do rock, and I also happen to love their representation in the art of painting. In your description of the wonderful watercolor of the blue hued rocks in the garden by Song Maojin, you mention that this color refers to moss etc. covering the rocks’ surface. I really hope that the museum, its visitors, and all passersby will allow their rock to receive the natural elements without filters, i.e. no brushing or cleaning or other human interventions, allowing natural organisms to slowly befriend this newcomer. While I don’t know the impact your local, San Antonio climate, flora and fauna might have on it, I’m thinking it would give this gift a nice way of feeling at home on the other side of the planet. Texas Proud! Art First! Ying Yang!

Thank you, Rama. And a rockin’ Yin Yang to you! It can be humid in San Antonio, but that long hot summer (which lasts most of the year) will probably mean that changes to the rock will come about very slowly. The transformations wrought by nature are inexorable, but often too slow to perceive in the brevity of a single human lifetime.

Thank you for this informative article. Your article definitely reminded me of the installation of this fabulous rock and the accompanying exhibition. Both had dropped from my got-to-do list. I am really pumped to see this now!

The rock awaits you, Norma.