This year’s symposium: Ron Tyler said that Mel Casas’ Humanscape #57 is among his favorite bluebonnet works.

The old Spanish Governor’s Palace in San Antonio stood shrouded in mystery and mostly unknown before its restoration in 1930. In Rolla Taylor’s undated painting of the colonial residence, the sleepy structure seems yet another sun-baked cantina adrift in some ancient dream that lingers on Military Plaza. Wispy, impressionistic figures on the sidewalk, one in a blue shawl and the other an orange serape and a straw sombrero, seem unaware of the building’s former grandeur as commandant quarters on the Nueva Espana frontier.

Rolla Taylor painted this view of the Spanish Governors Palace in San Antonio when it was still just another sun-baked cantina on Military Plaza.

I stumbled across the painting, reproduced in a Heritage Auctions Texas Art catalog, at last year’s sometimes spicy and always informative symposium of the Center for the Study and Advancement of Early Texas Art (CASETA), held at the Witte Museum in San Antonio. This year’s annual gathering of the statewide organization, held March 29-31 at the Texas Computer Education Association Conference Center in Austin, proved perhaps even more stimulating.

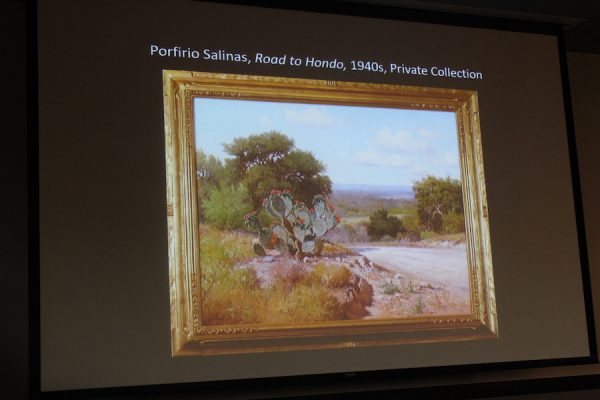

Longtime Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum curator Michael R. Grauer, who recently lit out for the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, unloaded the Friday evening Pacesetter Address, “Porfirio Salinas: Serious Artist or Potboiler Painter.” Placing Salinas’ work next to that of his influences — Seymour Thomas, Lucien Abrams, Dawson Dawson-Watson, Julian Onderdonk, Jose Arpa Perea — Grauer concluded that the Bastrop native “was a lot more sophisticated than we give him credit for.”

Citing Falfurrias artist Noe Perez as a contemporary painter who sings the praises of Salinas’ deft hand with prickly pear, Grauer noted that Salinas also passed the test of whether one can “taste the caliche dust” in his landscape paintings the way one may with, for instance, an Arpa work. And Grauer, author of Rounded Up in Glory: Frank Reaugh, Texas Renaissance Man, furthermore stated that he places Salinas’ 1940s painting, Road to Hondo, in his personal list of all-time top ten Texas paintings.

Curator Michael R. Grauer places Porfirio Salinas’ Road to Hondo among the top ten all-time Texas paintings.

You can see Grauer’s complete Salinas presentation here:

Susie Kalil opened Saturday’s sessions with a conversation with artist Roger Winter. I’ve long been a fan of Kalil’s curatorial work, going back to the 1986 MFAH show, The Texas Landscape, 1900-1986, so it was a double treat to learn about Winter’s eclectic trek through 20th and 21st century aesthetics with her as guide. And at 68 myself, I get super-juiced to see artists like Winter, 84, who are still discovering ways of seeing and responding to the world.

Born in the Red River burg of Denison in 1934, Roger Winter grew up with seven siblings in a four-room house without indoor plumbing. Gazing at railroad tracks 18 feet from the family’s front door provided much of his early experience with artistic perspective. His brothers and sisters say that as far back as they can remember, he was constantly drawing. For Winter, it seemed as natural as breathing.

“But I thought art was something done in Europe, many years ago,” he recalled at CASETA. “I thought all artists were dead.” So it was quite an epiphany when he hitchhiked to UT Austin in 1952 and first visited the art department, which at that time was in a former barracks building on Waller Creek. “It was both a revelation and a revolution to see the walls covered with student works,” he said. “That’s when I knew: this is what I want to do.”

And he has never stopped doing what he wanted to do. With residences in Dallas (where he taught at SMU), New York, Maine, Santa Fe, and Bandera — as Kalil chronicled his artistic arc — he has actively explored cubism, surrealism, photo-realism, magical realism, pop, hard edge, and just about every other school of artmaking one can conjure.

“Roger has, throughout his career, resisted categorization, art-world expectations, and almost any kind of authority,” Kalil noted. In 1971, Winter participated in an important show at SMU that rounded up eight artists who had been central to Dallas’ wrassling with the avant-garde (a perhaps unfortunate and imprecise term but a serviceable one) a decade earlier. Curated by the major figure Douglas MacAgy, the show, titled One I at a Time, included Winter, Roy Fridge, Bill Komodore, Jim Love, David McManaway, Hal Pauley, Herb Rogalia, and Charles Williams.

Dallas Morning News critic Janet Kutner wrote at the time that “only MacAgy could have pulled together this highly personal yet subjectively historical exhibition.” The show, she wrote, evoked “the freedom of spirit to pursue an individual approach to art.” She noted of Winter’s contribution that his “representational work on canvas almost speaks for itself. It is strongly autobiographical, essentially personal… . But the wonderful blend of today’s reality and yesterday’s memory is a compelling art form that communicates to anyone who can identify with similar ties and dreams.”

View the Roger Winter and Susie Kalil discussion here (and watch for Kalil’s forthcoming book from Texas A&M University Press, Roger Winter: Fire and Ice):

Many CASETA members are collectors. Michael Grauer referenced one of Texas’ most unique collectors, Fort Worth’s late A. C. “Ace” Cook, who frequently proclaimed about various works in his famous Hock Shop Collection, “That’s a national treasure!” A symposium panel discussion addressed issues raised by its title, “What to Do with Your Collection when You Run Out of Wall Space.” Moderated by Bonnie Campbell (“Good morning, fellow hoarders! I mean collectors!”), Director of the Bayou Bend Collection and Gardens, the panel included Austin collector Ted Lusher, attorney and SMU adjunct professor Andrea Perez, and DMA curator Sue Canterbury.

While the information presented may not have been surprising, it was nonetheless quite useful nuts-and-bolts data on what to do with an art collection — not only when one runs out of wall space but also when contemplating one’s exit from this realm. It certainly would have been helpful to Ace Cook, whose collection, before it found a good home, suffered from the legal limbo that often afflicts estates of relative wealth.

View that panel discussion here:

Though CASETA defines early Texas art as work created 40 or more years ago, that guideline is fluid, as evidenced by the selection of James Surls to deliver the symposium keynote, titled “Then, Now and Tomorrow.” As one might expect, Surls delivered the address with a craggy heap of art-star charm. He described a shamanistic type of art practice that involves a tendency to “go into another state of being” in which he uses imagery like a bridge to “enter another world.” He cited the example of a herd of several hundred elk that he heard moving through the Colorado pre-dawn. The sound of that natural event “spoke” to him and provided passage to that dream state in much the same way that the poet William Blake was able to see the universe in a grain of sand. “And that’s where my art comes from.”

Showing images of his pieces made from trees, with names like Black Bear Holding a Crooked Stick, She Brings Gifts to Me, Dancing Man, Night Vision, Swimming in Forever, and Walking in Immensity, Surls talked about the link between his raw material and the artistic impulse. The first of those pieces, he related, was sculpted from a huge ponderosa pine from the Kit Carson National Forest. A forest ranger explained to the artist that it was a partly dead “rogue” tree due to be cut down because of the fear that lightning might strike it and cause a fire. So Surls purchased it for two dollars.

Having grown up in the Big Thicket and having lived for years in Splendora, Surls affirmed his love for the stands of blackjacks and other oaks, the sweet gums and magnolias — not only as art material but also as front yard. Recalling an early-career Whitney Museum of American Art exhibition, in which his work shared space with that of Donald Judd and Jasper Johns, he revisited the realization that he relates more to Benjamin Franklin than he does to denizens of the high-art world.

See the full hour-and-a-half keynote address below. (Note: James Surls: With Out, With In is on view at the UMLAUF Sculpture Garden and Museum in Austin through August 18.)

Bradley Sumrall, curator at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans, presented a lively account of Texas art flowing across the Sabine, “Our Brother’s Keeper: Building an Important Texas Collection in New Orleans.” He concluded with a list of artists whose work the Ogden actively seeks, including Jerry Bywaters, Trenton Doyle Hancock, Roger Winter, Vincent Valdez, Deborah Roberts, Luis Jiménez, John Biggers, and Terry Allen.

Katherine Brimberry of Flatbed Press wrapped up Saturday’s sessions with “Dancing in a Matrix: Seven Texas Artists Step Onto the Printmaking Dance Floor,” a detailed account of the process in which artists have worked with the technical support of Flatbed’s master printers to produce etchings, lithographs, woodcuts, and linocuts. “The matrix is the surface that the image is created on,” Brimberry explained. “It can be carved, etched, and drawn on.”

After Flatbed’s founding in 1989, Robert Levers was one of the first artists to do an edition there. His matrix was a copper plate covered with soft ground wax, except for the places where he had drawn upon it. His print Victory to Celebration, Brimberry noted, “is possibly the most important print we have ever done at Flatbed.” Bert Long created his Flatbed monotypes by painting ink onto plexiglass to form the matrix. Kelly Fearing, a member of the Fort Worth Circle during World War II, used a hard ground copper photogravure process — and later, a photopolymer gravure process — at Flatbed. Melissa Miller combined soft ground and hard ground etching with aquatinting for works like her Water Spirit. “And we were able to create the effect of her brush strokes by including a soapy white ground plate,” Brimberry added. “It’s all about finding a way for an artist to work with the matrix.”

Brimberry first discovered James Surls in Annette Carlozzi’s book, 50 Texas Artists, shortly after moving to Texas in the mid-1980s. “I was astounded by the depth of Texas art,” she recalled. Her introduction to working with Surls began when she found an eight-foot-long piece of rolled-up linoleum he’d left on her porch. (It seemed to say, “Print me,” she joked.) He presented her with another challenge, printing on the front and back sides of a print, for a show at the Fort Worth Modern. A move to their site on Martin Luther King Blvd. in 2000 enabled Flatbed to do lithography for the first time, spending 18 months working on a print for John Alexander that involved some seven or eight plates. Falling victim to Austin’s wacky, inflated real estate values last year — a situation afflicting so many art organizations — Flatbed lost its MLK space. Happily, Brimberry reported at CASETA that a new space has been secured with an opening set for June of this year.

I met Luis Jiménez at Flatbed in 2006, when he came to create a print as a benefit for Texas Folklife’s live performance programming based on my book Border Radio. We talked about how he used to listen to the borderblaster XELO out of Ciudad Juárez while working in his El Paso studio. Weeks later, I was half-asleep in an El Paso Holiday Inn, with local TV news on, when I heard the tragic, surreal news of his death in his Hondo, New Mexico studio.

Brimberry recounted that Flatbed produced Jiménez’ haunting print Self Portrait in an uncommonly large edition of 50, a herculean task she vowed never to repeat. And while working on the Border Radio print, he also produced a chilling work based on the events at Abu Ghraib that were then in the news.

See Brimberry’s presentation here:

Liz Kim opened an abbreviated round of Sunday sessions with “Coreen Spellman’s Abstractions.” An Assistant Professor of Art at Texas Woman’s University in Denton and a South Korean native, Kim came to Texas two years ago and has since been immersed in studying art produced by Texas women and acclimating herself to our peculiar customs, which included the near-obligatory purchase of a pair of cowboy boots.

Kim led the audience through Spellman’s aesthetic development with surgical precision, covering her periods of working with representation and formal abstraction in oil painting, printmaking, watercolors, and collage. As hallmarks of Spellman’s work, Kim cited her use of deep black and her “deliberate application of tonal variety, whether fluid, subtle, or stark.”

Speaking of her painting Road Signs, one of the 1930s regional landscapes that best define Spellman’s career, Kim noted that the work’s “monumental geometric forms on thick columns pierce out from the dry, stark soil of North Texas, extending toward the dappled, atmospheric sky up above. These solid, sharply angled shapes defined in varying tones of industrial gray dwarf the sleepy slopes and sinking farmhouses in the horizon. The varying angles of the signs break apart the plane, as though each of those signs were on hinges.”

See Kim’s complete presentation here:

It was fitting that Ron Tyler’s session, “The Art of Texas: 250 Years—What I Have Learned,” closed out this year’s symposium. Tyler’s colossal project does exactly what the title indicates. It rounds up two and a half centuries of art making in our immense and beautifully unruly land mass masquerading as a mere state. I’m greatly anticipating seeing his current Witte exhibition that is partly of the same title, and the accompanying book.

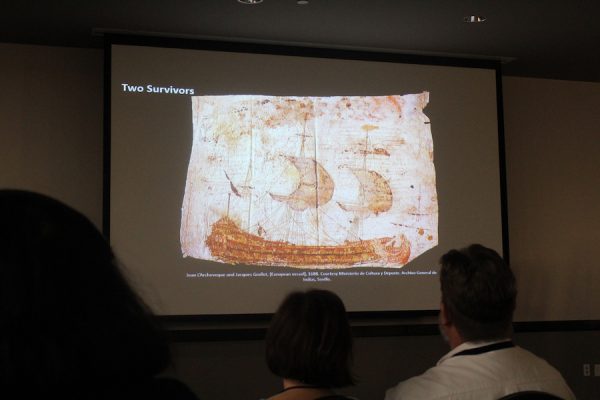

Two French survivors from La Salle’s doomed landing at Matagorda Bay in the 1680s created this image of a European vessel on parchment. They wrote a note on the parchment, stating that they were Christians and hoped to rejoin civilization, passing the parchment on to Native Americans who then passed it to Spaniards.

Tyler focused on some of his favorite images from the book and exhibition, starting with one of my own favorites, a 1688 drawing of a ship on parchment, produced by two of the survivors of the ill-fated La Salle expedition. The Frenchmen passed the parchment to Native Americans, who delivered it to Spaniards. From New Spain, the document eventually wound its way to the Archives of the Indies in Seville. A facsimile of the work appears in the show. “I went to the Archives once, hoping to see it,” Tyler said, “but I was only able to view a xerox copy.”

Another work shown in his talk, Tehuacana Creek Indian Council by John Mix Stanley (1843), demonstrates the need for research programs like CASETA. There remains compelling early Texas art still undiscovered. This painting remained in the Stanley family until just recently, when it was sold to the Stark Museum of Art in Orange.

I’ll soon be writing about the exhibition and book, so I’ll simply note here that Bonnie Campbell was so moved by Tyler’s accomplishment that she rushed the podium. “I think almost everyone in the audience understands what this man has overseen over the last several years to gather this exhibition, refine it, corral it, and envision it…” she said in heartfelt tones after commandeering the microphone. “I mean Ron has had an incredible career and has done many, many things, but honest to God y’all this is the most amazing production that you’re about to enjoy… . It’s the most difficult thing I can imagine someone trying to do.”

When the roaring ovation died down, the quick-on-his-feet Tyler cracked, “You might want to see the show first.” Can’t wait.

See Tyler’s presentation here:

****

Some other symposium highlights:

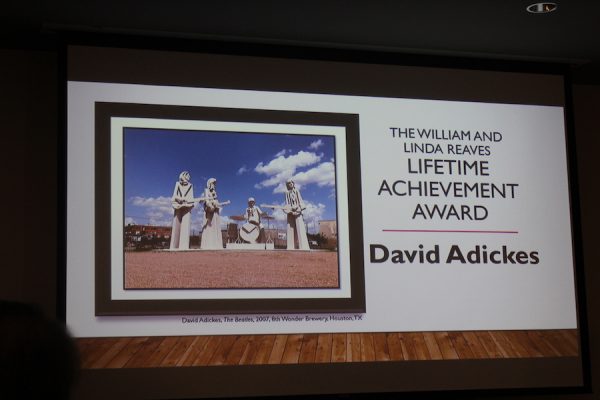

Ninety-two year-old David Adickes received the 2019 William and Linda Reaves Lifetime Achievement Award.

Sarah Beth Wilson (left), Katie Edwards, and Ron Tyler (right) present Peter Gershon with the CASETA 2019 Publication Award for Collision, his account of the Houston art scene from 1972 to 1985.

****

Each CASETA Symposium includes a Texas Art Fair with exhibitor booths populated by dealers from around the state. Charles Morin told me at this year’s fair that his San Antonio Vintage Texas Gallery, across the street from the McNay Art Museum, has a few dozen works by Rolla Taylor, the artist who painted the Spanish Governors Palace seen up top. Perhaps in some future symposium a regional art historian will delve into Taylor’s life and work. A quick history check of The Portal to Texas finds him painting and exhibiting in many Texas towns. His obituary in the July 31, 1970 Bandera Bulletin stated that the artist, who lived to the age of 98, had also been a violinist but supported himself as a court reporter, taking painting vacations throughout the Southwest and Mexico. As a boy, he had moved to San Antonio from Cuero with his family in a wagon.

1 comment

It’s Texas Woman’s University