The ubiquitous monarch butterfly, so named in honor of William III of England, makes a 3000-mile migratory journey from the state of Michoacán in Mexico all the way to Canada over multiple generations, and then back south again. It’s a chained cycle that spans a region extremely rare for butterflies to traverse. In Monarchs: Brown and Native Contemporary Artists in the Path of the Butterfly, a massive group show of 35 artists in two San Antonio venues, curator Risa Puleo assembles a dazzling array of brown (her term to include a complex and diverse aggregation of people referred to at various times as Hispanic, Latino, and Chicano) and native (e.g. indigenous) artists living or having histories in the corridor of the Monarch’s path.

In lesser hands, this ambitious show could easily become pedantic, weighted with specious scientific research and data and taking an overly literal approach to immigration and identity. Puleo’s approach is imaginative and immediate, and successfully telescopes out from a granular level — from the cloud-level resonance of history repeating, treaties broken, and promises by the white man just “talking leaves” (a Cherokee phrase) that blow away in the wind once signed. A common theme here is use of modern materials in ancient traditions, and the resolute survivalism passed across generations.

In a recent essay by Tom Scocca entitled These are the Bad Times, Scocca muses on creeping fascism in America, noting that even if the U.S. doesn’t become fully Nazi, to go a quarter of the way is bad enough. Socca concludes that the period of Reconstruction following the Civil War (after a brief moment where emancipated people held elected office) was such a successful campaign of racial terror that the Nazis actually studied it in the 1930s for guidance for shaping their ethnostate. Socca’s point is clear: These are the Bad Times, pretty much the same as they always were. For the artists in Monarchs, they and their families have survived through such times stretching across centuries, the respites brief like a few beats of a butterfly’s wings across the plains. Monarchs is steeped in history, but it doesn’t seek to merely explicate tragedy. The horrors of colonialism are treated as immutable fact. The exhibition’s clear-eyed lack of sentiment creates a launchpad for catharsis. As Puleo writes in the catalog essay:

“Many of the artists in the exhibition speak to the expectations of an art market and audience that desires the wisdom of the Noble Savage, or harrowing tales of traumas overcome by the Native and Brown artist. But rather than focusing on fault lines in the field of projection and stereotypes, or offering an analysis from the position of an embattled relationship with the past, the artists in Monarchs instead chose to focus their efforts on reconnecting and rebuilding the cultural lines that have been severed. In this way, these artists articulate notions of lineage, inheritance, and generational thinking differently from any group of artists in the past thirty years.”

For Monarchs, Puleo creates a matrix that spans time, using four events as a geographical and symbolic framework. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo from 1848, following the Mexican-American War, created the modern southwest, while the Treaty of Fort Laramie from 1851 established passage through native lands for settlers with dreams of gold. The modern counterparts to these two treaties are the Dakota Access Pipeline protests on the Standing Rock Reservation, and Trump’s plan to build a border wall. The echo is clear: Talking leaves blow away; new ones appear waiting for another gust of wind.

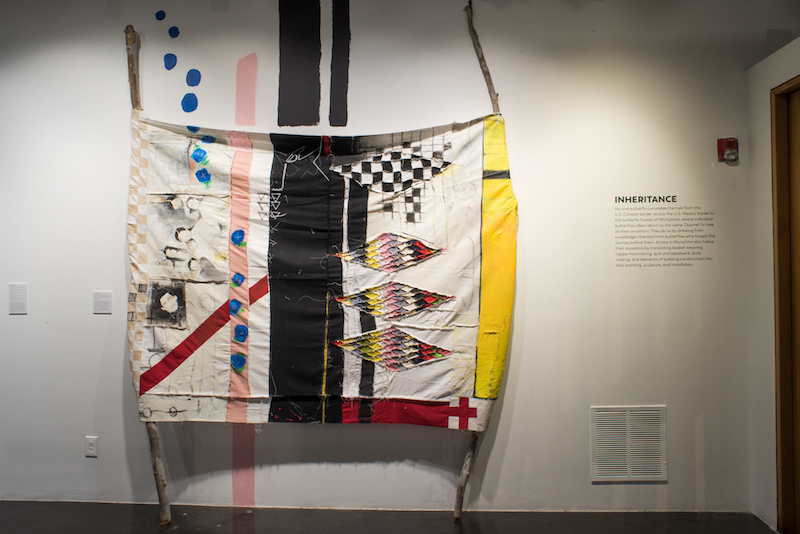

Puleo has divided the show into categories: Migrations, Inheritance, Transformation, and Resilience.

In Migrations, Guillermo Galindo, a Mexico City-born artist now based in Oakland, uses the orange and blue flags of the non-profit Water Station, which directs migrants crossing the desert to water so they don’t die of dehydration. In recent times, vigilante nativist groups like “the Minutemen” have taken to destroying such stations, which is not only a death sentence for some migrants, but also emblematic of a crescendoing racial vitriol. Galindo uses sun-bleached, wind-torn decommissioned flags that communicate the heft of the desert and its elements. In Siguiendo Los Pasos del Niño Perdido/Following the Steps of the Lost Child, Galindo embroiders a nightmarish, loping trail of a child lost in the desert. The counter ballast is Cartografía del Espíritu/Cartography of the Spirit, a flag embroidered with constellations forming a map. The two flags together take on a mythic, Odyssey-like gravitas, with the migrant or refugee thrust into the stark symbolism of a fable.

Cannupa Hanska Luger, an artist originally from the Standing Rock Reservation, and Marty Two Bulls, Jr., an artist from the Pine Ridge reservation, create the most devastating piece in the entire show. Wasted is a tableau of ceramic beer bottles and booze jugs decorated with bulls-eyes and arrows sticking out. The message is painfully clear: the scourge of alcohol brought by whites was often used as a tool of oppression and control of native populations. The catalog notes the “town” of Whiteclay, Nebraska, just outside the Pine Ridge reservation, which serves as a liquor depot — a faucet of misery, violence and despair flooding the dry reservation. The installation stretches out like a last supper. One can simply squint and see it go on forever — all the wasted lives, the wasted times, the never-ending racks of bottles carried on trucks blotting out the sun.

In the show’s Inheritance category, Carmen Argote’s My Father’s Side of Home is a cotton cloth called manta traced with the architectural features of her family’s ancestral home in Guadalajara, to create a kind of ghostly simulacrum of the interiors. The cool color palettes and graphics recall formalistic, architectural schematics, and raises questions around ideas of authenticity and the sentimentality of memory. An interview with the artist and writer Guillermo Gómez-Peña is excerpted in the catalog, where he states:

“To me, authenticity is an obsession of Western anthropologists. When I am in Mexico, Mexicans are never concerned about this question of authenticity. However, when I am in the United States, North Americans are constantly making this artificial division between what is an “authentic” Chicano, an “authentic” Mexican, an “authentic” Native American in order to fulfill their own desires. Generally speaking, this authentic Other has to be pre-industrial, has to be more tuned with their past, has to be less tainted by post-modernity, has to be more innocent and must live with contemporary technology. And most importantly, must have a way of making art that fulfills their stereotypes; in the case of Mexico — Magical Realism.”

Argote’s piece subverts this idea, and in the process expands the aestheticized associations of cultural memory and inheritance. Similarly, Sky Hopinka’s arresting and gorgeous video piece Jàaji Approx dreamily chronicles his process of learning the near-extinct Chinook Wawa language. The video is elliptical and non-linear, and often doesn’t translate the Chinook Wawa words and phrases. There is a purposefully and beautifully confounding quality to the work — a current throughout the entirety of Monarchs — that some knowledge and formulas are beyond, just over the hill and behind the sunset.

In the show’s Transformation section, Natalie Ball’s June 12 & 13, 1872 uses the native trickster mythology of the coyote as a transgressive spirit of change and adaptation. The title refers to a time one month before the Modoc War when Ball’s ancestor defeated American troops trying to remove the Modoc people from their ancestral lands in Oregon and California. The trickster is ubiquitous throughout native mythology through different forms such as a coyote or raven. In Lewis Hyde’s seminal book Trickster Makes the World, the trickster is an essential part of creativity and transformation. Its trick — be it changing forms or stealing something forbidden (such as fire or the “light box”) — often serves as a catalyst for progress or survival. Ball’s piece posits that the trickster spirit is essentially wired into the identity of native people, and that such transformation is required to slip the trap and keep going.

Mary Valverde’s Untitled (Altar with Offering) combines Andean geometry with Catholic altar design in Ecuador. (Valverde’s work is pictured at top.) Valverde uses everyday materials to accentuate that a mystic cosmology is not dependent on rarity of materials or even a religious belief system, but something deeper and more elemental. This is a recurring theme throughout Monarchs — an ineffable spirituality glowing behind a hard-edged endurance, when something transforms if only for a moment, a flash, enough to keep a dream alive.

In the Resilience section, Guadalupe Rosales documents Latino party crews from the LA rave scene of the 1990s and early 2000s. Cataloguing flyers as well as digital archives from social media such as MySpace, Rosales reclaims an era, away from xenophobic hysteric stereotypes of gang violence and misery. The whole of Monarchs, in fact, is an act of reclamation — of land taken, identities erases, histories laid flat and barren. This reclamation is like light through a glass prism, with the patterns charged and dancing.

These are only a few highlights of a truly epic show, one that demands multiple visits to both venues. The feat accomplished by Puleo and this cadre of artists is staggering. It surveys the hell-world we’re living in and asserts something else, and beats its wings and rises to view at least the dream of a new world — a dream that has always existed.

Through January 6, 2019 at Blue Star Contemporary and Southwest School of Art, San Antonio