Justin Boyd in his studio. (Photo: David S. Rubin)

For more than fifteen years, San Antonio artist Justin Boyd has explored formats that unite sounds with visual forms. His sound elements drive the visual ones, and Boyd creates sounds to fill individual objects, entire exhibition spaces, and outdoor settings. Both a conceptual artist and practicing DJ, he approaches each project much like a recording artist developing a concept album, and often explores a theme or idea using techniques that are common to music production and DJ culture: dubbing, splicing, and mixing, primarily using analog audio technology. A descendant of Texas ranchers and farmers, Boyd has focused much of his artistic production on subjects relating to American wanderlust, in the same adventurous spirit that led American pioneers to cross unknown territories as they journeyed westward.

Currently the Chair of Sculpture & Integrated Media Studio at the Southwest School of Art, Boyd started out by studying sculpture, ceramics, and art history at the University of Texas at San Antonio, where he earned his BFA in 1997. While still a student, he accepted a dream opportunity to work as a studio assistant at Artpace, where he participated in the making of Christian Marclay’s acclaimed video Guitar Drag, in which we see and hear an electric guitar destroyed as it’s dragged by a truck moving through the Texas countryside. After working with Marclay, Boyd went on to study for a summer at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture and then entered the graduate program at the California Institute of the Arts, where he earned an MFA in Art and Integrated Media in 2003.

Left: The Idle Role of an Action Hero, 2003; right: Our Collapsed Star, 2003

In Boyd’s earliest sound sculptures, his ties to pop culture are particularly evident. During his final year of grad school, he created works using the voices of movie stars and a legendary singer as raw material, which he transformed and recontextualized. For his project The Idle Role of an Action Hero (2003), Boyd installed two minimal sculptures that function like musical instruments and look something like Donald Judd boxes with telescopes. Positioned adjacent to each other, the sculptures play vocal samples of dialogue spoken by Vin Diesel and Arnold Schwarzenegger in action movie roles, with the idea that here they are in a competition—it fits the action-hero mold and is also reminiscent of a high school battle of the bands. Each telescope is actually an automobile muffler fitted with an internal speaker, through which we hear a Diesel “hum” and a Schwarzenegger “purr,” the results of the mufflers phasing and transforming the vocal samples which Boyd altered through techniques known as pitch shifting and time stretching. In the end, what we hear sounds mechanical, in deliberate reference to the often robotic nature of action heroes.

The voice of Billie Holiday provides one of the two sound sources for Our Collapsed Star (2003), a work that pairs Holiday’s singing with the sound of the black hole at the center of the Milky Way, which Boyd obtained from NASA. Rather than contrast the sounds in this installation, Boyd instead equates them in a way that illuminates Holiday’s reputation as a major star in our history of singing artists. The installation, consisting of two parts, features the Milky Way’s center in the form of a rectangular subwoofer with an attached curtain that flaps in response to the subwoofer’s sound vibrations. Connected by visible wiring to and located opposite the black hole sculpture is a metaphoric portrayal of Holiday—a radiantly spotlit vintage phonograph that spins a light reflective recording produced by Boyd, which merges the two sound sources into one. To incorporate the idea that time is fleeting, he recorded the tracks in a single pressing, which can be played only a finite number of times before the sounds fade away.

Pulling a Folk Thread Through an Ether Quilt, 2005

In 2005, Boyd presented his first in a series of exhibitions about American wanderlust. Exhibited at Sala Diaz in San Antonio, Pulling a Folk Thread Through an Ether Quilt is a three-part installation project that fuses found and constructed objects, audio equipment, and controlled sounds to create a metaphoric orchestra, with each section articulating ideas related to Boyd’s musings about the pioneering spirit of colonial Americans. As in earlier works, all three sections of the Pulling a Folk Thread ensemble are united by being tuned to the identical key.

In the first section, Our Lost Spirit, a Paul Revere style tea kettle plays a “teasong”—sounds produced by tuning the kettle with a pitch pipe and heating it with a hotplate. Metaphoric content emerges from the contents of the tea: herbs associated with strength, wisdom, and vision, and from a wall-mounted drawing that acts as a score. The score features only a single note and a depiction of the historic battleship the U.S.S. Constitution, and is titled “Sound the Alarm Our Last Spirit Tea,” which is Boyd’s subtle commentary about the then-sitting President, George W. Bush.

The second and third components of the installation include The Pull of the Near and Draw of the Far (Vocal Butter Mix) and Revelation Through Repetition (Vocal Thread Mix). The former structure is fashioned to look like an antique butter churn, and mimics the motion of a turntable by playing a blended mix of samples from Native American, Shaker, and African American religious folk tunes as the plunger revolves round and round. The latter work pays homage to Christian Marclay’s Tapefall (1989), a well-known installation where reel-to-reel tape moves through a projector and lands on the floor to the sound of its contents: a recorded waterfall. In Boyd’s installation, the audiotape loops through a vintage tape recorder and spools positioned atop two industrial towers located at opposite ends from the recorder. Its soundtrack is a time-stretched mixture of “exhales” and “yodels” by classic American folksingers, including the trailblazing Jimmie Rodgers.

An Effort Against Being Lost, 2007

Part two of Boyd’s search to define the American spirit centers on life and travel along the Mississippi River. Titled An Effort Against Being Lost and featured in the 2007 Texas Prize exhibition at Arthouse in Austin, the project is made up of three related sections. In the first, Yew Tree Gate, Coal Tape, a wooden sound sculpture is based on a tree species known for its longevity and regenerative powers (when it dies, it sprouts a new tree). Since ancient forests have often decomposed to form coal beds for millennia, the “food source” for the tree is a tape recorder that sends the sound of combusting coal up and down the tree repeatedly as the sound alternately amplifies and diminishes. Viewers walk under the gate to experience the partner sculpture, A Hope Well, which contains an interior echo chamber that transforms visitors’ voices (including private utterances). The second element of the installation is Flux Raft, a raft made from types of wood carried along the Mississippi River. It has a screen for a sail and is flanked by topiary plants associated with the South. The projection features footage of the river along with sounds of vintage recordings from the collection of Boyd’s grandfather. The installation’s final element, Flux Map, is a drawn map of the United States, with emblematic references to the two installations completed at the time, positioned in their appropriate geographic locations.

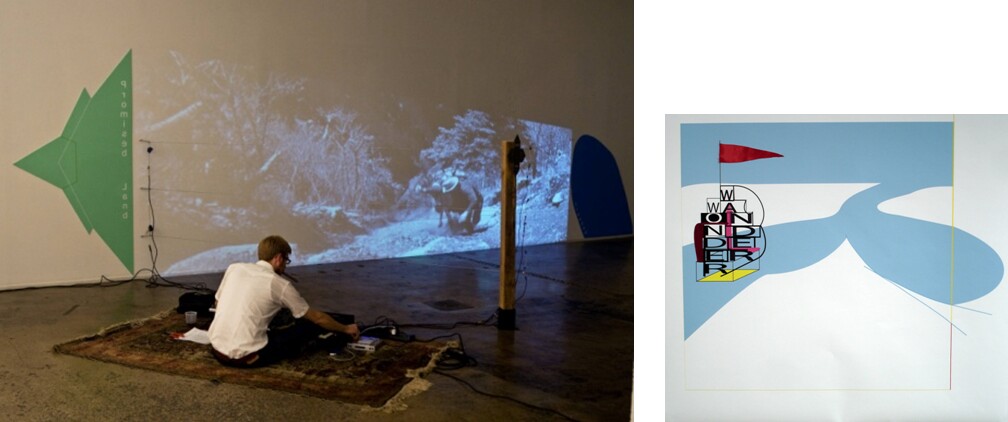

Lonely Are the Brave, 2009

Having traveled metaphorically through 18th and 19th century America, from the Eastern shores to the Midwest and the South, Boyd next decided to tackle the 20th century and the iconic highway Route 66. For his 2009 exhibition at Blue Star in San Antonio, Boyd exhibited several digital prints on the subject, including Wonder Wander, where a raft carrying the title phrase is shown heading up a river towards the wild blue yonder. The exhibition’s showpiece was the video installation Lonely Are the Brave, based on the 1962 film adaptation of Edward Abbey’s novel starring Kirk Douglas as a fugitive cowhand who refuses to accept modern technology, and prefers a horse to a car. In one scene of the film, the cowhand struggles to pull his horse up a steep hill, but the two keep sliding back down. In his installation, Boyd projects this scene behind a fence and on a continuous loop, turning it into a Sisyphean sequence about the challenges we face as we pursue our goals.

Time Has Slipped Rows, 2012

The final chapter of Boyd’s American saga, Time Has Slipped Rows, brings us up to the 21st century. Installed in 2012 at the Old Jail Art Center in Albany, TX, the three-part installation investigates the artist’s native Texas ranchlands, combining autobiographical content with references to the region’s landscape, its history of slavery, the Dustbowl, migration, the desire to build a new life, and outer space. As an introspective look into the artist’s heritage, current situation, and prospects for what lies ahead, each section is filled with objects that function as instruments of sound, with the speed of the sounds accelerating as they move from past to present to future.

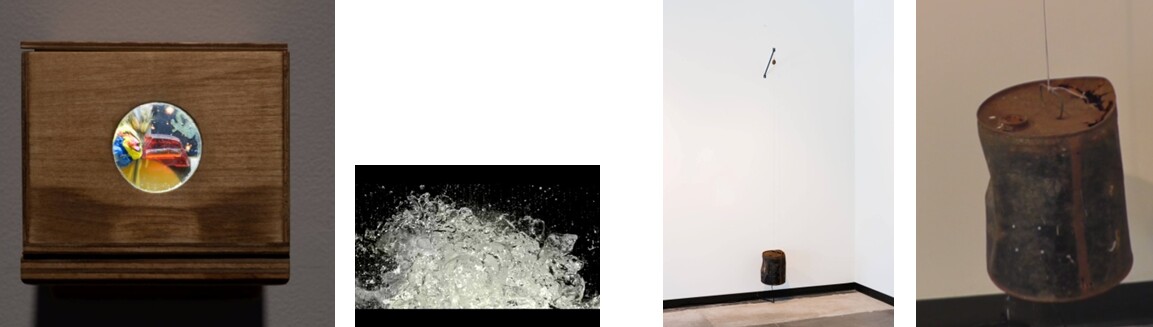

Left: Days and Days, 2012 ; right: Vibrational 1, 2013

Since completing his four-part odyssey, Boyd has been concentrating on the everyday landscape that surrounds him. Without sacrificing any of the inquisitive sense of awe that has motivated his large-scale installations, his recent works are simply more intimate. That is to say, wander has turned to wonder. For his Days and Days exhibition in 2012 at the Southwest School of Art, Boyd installed a series of sound assemblages that celebrate the earthly beauty of the San Antonio River, while also calling attention to the detritus left behind by careless people. Constructed of wood and designed to look like a peephole camera, each River Collage Box houses an interior assembly of natural and industrial objects found in the river, which interact with audible video projections of moving water. In the subsequent work Vibrational 1, Boyd contrasts the decaying surface of a rusted canister with ethereal sounds contained within it—an otherworldly fusion of ringing bells and chirping birds.

Two Tracks, 2014; The Young Die Before the Old; Why Do Birds Sound Like Car Alarms Now? 2015

Most recently, Boyd is actively exploring ideas about energy and motion through a variety of modes. Two Tracks (2014), for example, is a visceral video projection created by using a modular synthesizer to merge visual images and audio signal patterns of a moving train. By contrast, The Young Die Before the Old is a poignant elegy to disabled veterans. A metaphor for a soldier who has returned home with one leg missing, the sculptural element consists of a green fiberboard panel representing a field and a pair of blue jeans with only one leg stretched over a stovepipe. The score that hangs next to the sculpture is that of Edward Bagley’s military march National Emblem with every other note removed—a subtle reference to amputated body parts as well as a compositional device to slow down the march playing in the stovepipe, which is adjusted to the reduced ambulatory pace of the wounded soldier.

Boyd is one of the artists invited to create a permanent site-specific installation for the newly opened Yanaguana Gardens, a playground in San Antonio’s downtown HemisFair Park. Why Do Birds Sound Like Car Alarms Now? provides an immersive sound experience for visitors walking along the historic Acequia, a path that once was the route for travel from the Alamo to other missions. With Boyd’s help, as we contemplate the past while retracing the steps of San Antonio’s ancestors, our consciousness of change is heightened. Using recordings from the site, Boyd has altered and transformed the natural vocals of insects and birds to draw out their similarities to the mechanical sounds of car and truck horns, creating an amplified 21st-century orchestra.

Justin Boyd’s new installation ‘Going On Going’ is at Blue Star Contemporay in San Antonio through May 8.

Note: Video clips of many of the works mentioned in this essay can be found at www.justintaylorboyd.com.