Rachelle Vasquez loves animals. Before she began teaching art at the Glassell Junior School, she worked as a pet-sitter. Over the last year I’ve been taking my dogs, Hannah and James, to the dog park to socialize with other dogs. What I’ve learned is that dogs are pretty clear mirrors of the people at the other end of their leashes. Vasquez’ work, now up at Box 13 in Houston, explores representations of a variety of animals, domestic and wild, but at the center of her work is the relationship between humans and animals.

More specifically, Vasquez’ work is about her relationship to animals. And this is a good thing. If the work was about the relationship of humans (in general) to animals (in general) the exhibition would be deeply depressing. Humans rule over the animal kingdom with a totalitarian nonchalance that often stems from plain indifference. But instead of giving the viewer Cujo or Planet of the Apes, Vasquez exhibits a thoughtful series of wall-mounted fabric sculptures built around animals who, for humans at least, have been imbued with certain mystical attributes.

Vasquez works primarily with the process of crochet but has also made several series of drawings. As she writes in her statement for her new exhibition, Those That Feel the Influence of The Stars, her work is often based on research into historical and fictional stories that connect human beings and animals.

In an earlier series Where Pigeons Dare, Vasquez made clean, simple line drawings of pigeons that had earned The Dickin Medal, the highest honor an animal can receive, for their service in World War II. The charm in Vasquez’ work lies not just in the sentimentality with which most of us view animals, but also in the total absurdity of our relationship to them. The pigeon does not care, understand, or care to understand the concept of a medal. The medal is for us.

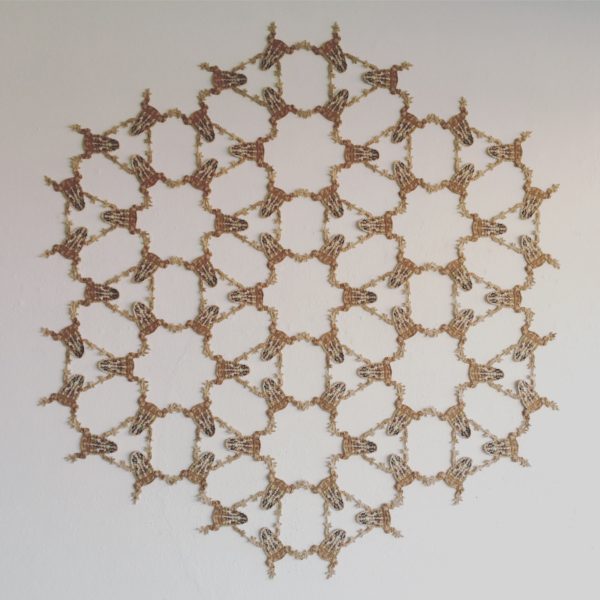

In the new show, her Brown Rats recall witches’ brews and dank cellars, but, their tails tied together to form a hexagon, they also remind us that just as the hexagon is one of the most common geometric units in the microscopic world, the world of the rat comprises a substructure to the human world. The brown rat is, in terms of worldwide distribution, perhaps the second most successful mammal on the planet after humans. Wherever there are humans, there are brown rats. Keeping mostly out of sight, they live in our walls, scurry through our alleys and reproduce in our vacant lots. Do we think about rats? Do we care about rats? Not really. An entire species is mostly just a nuisance or a means to scientific ends. Vasquez gives the rat its day.

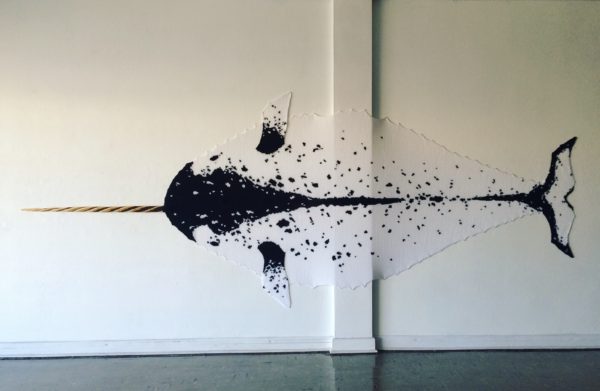

The crochet method prevents the animals represented in Vasquez’ objects from becoming anthropomorphized. Her Narwhal, which, from tusk to tail, seems to be over ten feet long, distances itself from cutesy or cynical charm with its scale and solid, time-consuming craft. The Narwhal is a whale, sometimes referred to as the unicorn of the sea, with a tooth so large that it protrudes from its head like a horn. The narwhal population is believed to be around 75,000, making it a threatened species. Stretched across a column on the wall, this knitted sea unicorn seems like a pelt, a specimen. With several of these whale populations observed to be in decline it’s hard not to see Vasquez’ Narwhal as an elegy for an animal that might someday be as rare as an actual unicorn.

Gulf Coast Toads, like the Brown Rats, are linked together to form an overall hexagonal shape. Looking at it I was reminded of the honeycomb design of the wasp’s nests I destroyed last summer when they began to invade my studio. Though Vasquez’ toads seem alive, I also couldn’t help but realize that the only time I see toads (or are they frogs?), they’re smashed flat by car tires and burnt black by the Texas sun. I like Vasquez’ work because she doesn’t push an agenda on the viewer. It’s clear that she has a complex psychological relationship to the animal kingdom, but her work is open enough to allow me to understand, on my own, that I don’t really. I should probably do better, be a little more careful about where I step and how big my footprint is.

This is slow art but it’s also intimate art. Whether they’re pinned to a wall or wrapped around a neck as a scarf, Vasquez’ objects are warm things. They’re domestic things, ultimately. There’s a tension, gently played on, between the feeling of domesticity inherent in crochet (your grandmother’s quilt you cover up with while you watch slasher flicks), and the domestication of animals to human ends.

One of the most important aspects of Vasquez’ process is its commitment to a hand-made method that can’t be rushed. Slow art, in a society in which few people even have time to think, is comforting. It’s a relief to know that artists like Vasquez are carving out time to contemplate a world of beings that are too often invisible and insignificant in our daily political decisions. If we think (as I do) that contemporary art is primarily a form of resistance against the cheap, stupid and superficial, then Vasquez is fighting the good fight.

I own a brown rat named Lita, from a previous series In Memoriam, in which Vasquez made deadpan “pelts” of her former, now-dead pets. For Vasquez, Lita is a reminder of an animal that she fed and cared for. For me, it’s an artwork that compelled me enough to support a fellow artist. For Hannah and James, who bark at the piece whenever they catch a glimpse of it on the wall by the bed, Lita might as well be a brown rat.

Through Jan. 7 at Box 13, Houston.