The skeletal remains of Reata, the grand facade of a Victorian mansion built near Marfa for the 1956 film Giant, stand like the crumbling bones of some impossible dinosaur that refused to fold into the earth. Or some alien shipwreck that outlasted an ancient sea, its creaking timbers moaning and defiant in the West Texas wind.

The artist team of Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler spent two years filming the ruin in all seasons and weather conditions. Its ghostly presence and the landscape in which it lingers play major roles in their three-channel video installation, Giant (2014), part of Sound Speed Marker, a trilogy of video installations on view at the University of Houston’s Blaffer Art Museum that also includes the two-channel work Movie Mountain (Méliès) (2011) and the single-screen Grand Paris Texas (2009).

Their curiosities piqued by having seen Wim Wenders’ 1984 film Paris, Texas while growing up in Australia and Switzerland, Hubbard and Birchler visited the small East Texas city of Paris, 20 miles south of the Red River, in 2007. There, exploring potential turf for their photographic series Filmstills, they discovered the abandoned Grand Theater. With a history going back to the silent film era, the Grand and collective Parisian memories of the theater proved to be rich in what Fairfax Dorn of Ballroom Marfa, writing in the Sound Speed Marker catalog, calls “the physical, social, and psychological traces that movies leave behind.”

Interviews with local residents, from the Paris News film critic to an elderly woman who ran the theater’s candy stand in the 1930s, excavate and interpret the movie palace’s past. The camera lovingly documents old projectors, film reels, lobby posters, and other relics resting in situ in the theater ruins. In a catalog interview, Hubbard notes that the artists “took a risk in allowing the circumstances of our research and the specificities of the location to shape the form of our film.”

Thus, Wenders’ 1984 film itself becomes a character in Grand Paris Texas. Musing on the German director’s work, residents wrestle with elucidating a storyline and theme that, back in the day, vexed certain smartypants regional critics. Paris News critic Toni Clem had no such problem, describing the 1984 film’s arc of estrangement and aching sadness. She recalls a special red-carpet showing of Wenders’ work at the Grand, as a fundraiser for restoring another historic Paris theater. Baffled that Paris, Texas bore their town’s name even though no scenes were filmed there, many left the Grand that night a little ticked off.

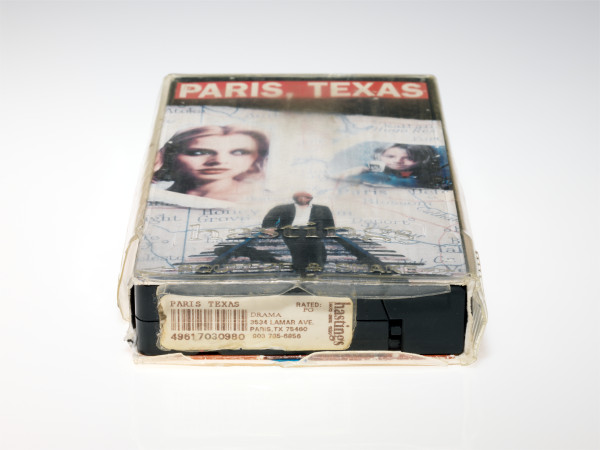

The artists acquired the city’s lone VHS copy of Wenders’ film after learning that the ending had been inexplicably taped over with a section from the 1925 silent film Tumbleweed, a King Baggot feature starring William S. Hart that screened at the Grand in 1926. And for still more filmic serendipity, Hubbard and Birchler interview Parisian Allan Hubbard (no relation), who at age 9 appeared with Robert Duvall in the 1983 film Tender Mercies. Duvall came to Paris for Allan’s birthday party after the shoot wrapped, gifting the boy with his first guitar. The adult Hubbard’s fine guitar work soars in the Grand Paris Texas soundtrack.

The comments of another interviewee, student Elric de la Pena, on the difference between films and movies, prove (for those who might need such proof) that one can experience cultural enrichment even when living in the sticks. The old folks, however, prove the most compelling interview subjects. The odds and ends of their personal spaces and the roadmap lines on their faces underscore an authenticity that shatters the clichés established by much of the Texas film canon. This is especially true for the trilogy’s second work, Movie Mountain (Méliès).

In April 1911, a silent film company headed by Gaston Méliès (lesser-known brother of the famous filmmaker George Méliès), left its Star Film Ranch home in San Antonio and headed for Hollywood by train. En route, they stopped for a time at Sierra Blanca in far West Texas, and according to local legend, shot a silent Western on a nearby rise in the desert plain. The site became known as Movie Mountain.

Though Hubbard and Birchler unearth no smoking gun by conclusively proving the shoot-em-up was made, it’s a much better story because of the mystery. The artists gather wisps of memory and legend about the softly-fabled shoot. Christina Ramirez, whose Apache ancestors moved north of the Rio Grande in 1910 to escape the Mexican Revolution, shares family tales about her uncle José Sanchez and his friends, who are said to have ridden horses in the film. Interviewed in the Sierra Blanca cemetery, Gary Jennings’ account is supported by the silent testimony of his grandfather Charlie Norton, who often told his descendants about appearing as a roper in the storied flick. His grandfather, Jennings says to the camera, “loved his horses more than people.”

Hubbard and Birchler film ranch workers herding cattle near Movie Mountain with a simplicity that is mesmerizing as the animals and riders move between the two screens. One of the herders on horseback, a beautiful blonde woman in a black cowboy hat, looks into the camera with a sureness that establishes her as solidly as any of the men, further dissolving a century of cowpoke clichés. Another of the cowboys, David Armstrong, shares his own traces of the illusory spell of images and stories on silver screens.

In 1975, this same Armstrong appeared as an extra in the film When You Comin’ Back, Red Ryder? shot in Clint, near El Paso. Telling the story with an appealing aw-shucks tone, he relates that he and a buddy then wrote their own Western film script and got an offer on it from a major production company. But Armstrong balked upon learning that he would not get to appear in the film himself. “I always felt like I could act,” the cowboy drawls. [Note to David Armstrong: Hell yes you can act, hombre. As Will Rogers said, “An actor idn’ anything special. He’s just a fellow with a little more monkey in him.” Get your monkey mojo workin’.]

In the trilogy’s concluding piece, Giant, the artists dispense with the interview process and instead explore the impact of the 1956 Hollywood blockbuster Giant through a bifurcated methodology. Part of the work re-creates a Warner Brothers Los Angeles office on February 9, 1955 as an actress portraying a secretary types the location contract securing the use of the land on which Elizabeth Taylor and Rock Hudson’s big-country crib Reata was constructed.

As one might when working in an industry devoted to creating fictional universes, the secretary often gazes into the distance, daydreaming. The scene shifts to the ruin of Reata as all three screens fill with the structure’s expansive location on the Trans-Pecos plain. The artists engage both the vastness of the scene and its minutest details. A grasshopper, enlarged exponentially, takes on a heightened visual reality. The changing light through seasons and hours relates some huge drama of its own that we can only fully grasp through experience and memory. With the three screens spanning the long gallery, the viewer’s immersion in the Reata-scape can take on a meditative quality. At several points, the immense horizon and sky disappeared before I was ready to let them go, yanking me back from a timeless zone and into the not-unpleasant confines of the 1955 office.

In her catalog essay, Blaffer Art Museum director Claudia Schmuckli notes that each of the three films visualizes its “productive dynamic through a recurring image that materializes its protagonist’s modus operandi.” Specifically, these recurring images are the 35-mm film reels seen in Grand Paris Texas, the cowboy’s lasso in Movie Mountain (Méliès), and the typewriter ribbon in Giant.

Indeed, the extensive close-ups of the keys striking the ribbon and making a letter appear on the page provoke an uncanny response in one who recalls forming words on paper in such a manner. It is, oddly, both foreign and familiar. And at this late date, the presentation of such language-making reminds me of the mystery of petroglyphs, incised upon stone by human creatures one can only imagine.

“Obsolescence in its many forms is a recurring motif in our work,” explains Teresa Hubbard in the catalog interview. “In the Sound Speed Marker, we depict a procession of obsolescent technologies and the objects associated with them… . The portrayal of these cultural artifacts could be seen as markers and placeholders for people’s lives and experiences.”

Cabinet senior editor Jeffrey Kastner remarks that Hubbard and Birchler’s work presents an experience that remains with him for an uncommonly long period of time, as do “the stories the videos tell and the often unexpectedly moving ways they tell them.” When I left the Blaffer, I felt I could have watched each piece another 17 times, especially the last two, and still felt enlivened and refreshed. Part of that sense, no doubt, is due to the invigorating challenge of the work. As Alexander Birchler explained in a PBS Art21 interview, the work encourages the viewer to “participate in the authorship of the story.”

Me? I like to make stuff up. And I suspect that you do, too.

Sound Speed Marker is at the Blaffer Art Museum through September 5. Grand Paris Texas (54 minutes) screens every hour on the hour. Movie Mountain (Méliès) (24 min.) and Giant (30 min.) each show in continuous loop. http://www.blafferartmuseum.org/

Note: Wim Wenders has just published Written in the West, Revisited (Distributed Art Publishers), a collection of images made while exploring potential locations for the film Paris, Texas. The new edition includes 15 previously unpublished images from the town that gave the film its name.

Images courtesy of the artists; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York; and Lora Reynolds Gallery, Austin

1 comment

I so admire Hubbard + Birchler’s work, and Gene Fowler’s review is a worthy and freshly considered counterpoint to their eye-opening observations. Looking forward to reading more of his features and commentary on glasstire!