Voces de las Perdidas (Voices of the Lost), site-specific installation, 2010. Ceramic body bag tags, soil from crime site, dimensions vary.

The Exploring Latino Identities series examines issues in Latino/Latin American contemporary art through interviews with artists, art historians, and others. In today’s installment, San Antonio artist and recent UT MFA graduate Adriana Corral talks about using her art to fight the silence surrounding acts of violence.

Lauren Moya Ford: What brought you to your current body of work?

Adriana Cristina Corral: Growing up in El Paso, Texas the femicidios (women murders) in Juarez, Chihuahua, Mexico is something that I have always been familiar with–usually by hearing about in the news or reading about it in the newspaper. The majority of the victims are often times young, beautiful, vulnerable women–students or maquiladora employees or both. The murders really spiked after NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) when an influx of women migrated from other parts of Mexico or South America to work in the maquiladoras (assembly plants on the Mexico-US border where many of the victims are employed) for better pay. In this body of work, I wanted to create pieces that inform the viewer of these tragic and silenced events that have happened and continue.

LMF: Why do you use text to deal with violence?

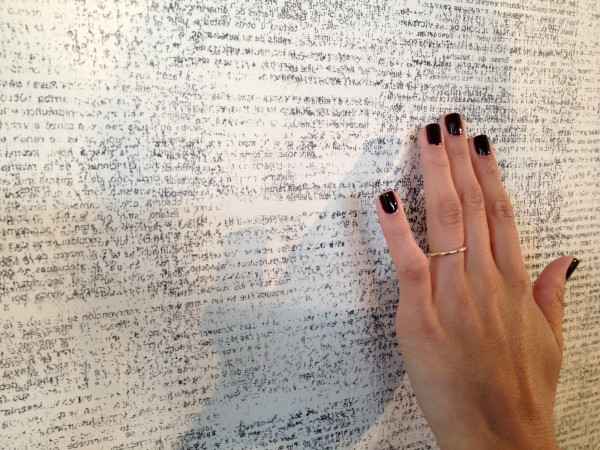

ACC: The text becomes, for me, an extension of the victims, a remnant of their existence. Sometimes these lists of names or suppressed documents are all that is left to memorialize these women and to provide a link to their tangible being. The text is structured to imitate the classified legal documents, which in most cases are covertly blotted and blacked out in order to keep the information obscured from public readers. This presents to me a way of protecting the content of these classified documents. The text is a way of communication. It allows me to read about it, to be informed about it, and to be able to talk about it. When transferring the text to the surface, I apply layers upon layers of text one on top of another creating a haunting effect by blurring itself. Creating these layers really mimicked how I felt about the crime: confused and trying to make sense of it all. I felt an urgency to translate this sense of confusion, and the piece ended up taking on a life of it’s own. For this particular installation, I have to keep the documents with me at all times, tape off the area, and the assistants have to sign waivers. Once the text is applied, all of the documents are burned, and I save the ashes, that’s what I’m left with. I’m not interested in shocking the viewer with an image of a crime scene or mutilated corpse. Instead, I want a person to come and engage with the work and learn about it without responding to a violent image. I often feel that people have become numb to sensationalized imagery and the intention of my work is give homage to the victims and the manner in which they died.

LMF: Your work transfers the horror of real world events into visual art pieces. Can you talk about your process?

ACC: I have to work with something that I’m extremely passionate about. Once I have that, I become engaged with research. I often find myself becoming internally connected to these tragedies and events, and it’s ultimately my goal to translate that sense of mourning, silence, outrage, and memory through installations and sculptural objects. For me, it’s like going through the stages of grief. In creating works in this manner I feel viewers can connect more to the subject matter because in some way all of us have to deal with loss.

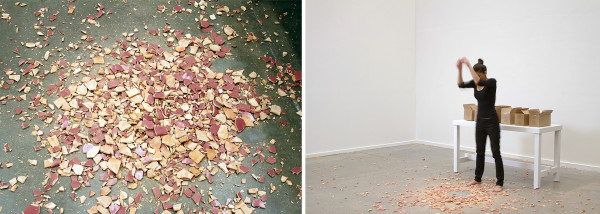

The research and materials I have gathered often dictates the work. For this series, the Campo Algodón (Cotton Field) murders really resonated with me. In this case, eight young girls were found murdered, and their bodies were left in a cotton field in the center of Juarez. It was as if the criminals were making a flagrant statement. I too, am making a statement by restaging the discovery of these disfigured bodies. Rather than finding their unsightly remains, the viewers encounter a memorial. Each of the works that I create goes through a rigorous process that is carried out with a considerable amount of time, care, and fragility. Their temporality becomes important in the sense that the recycling of these materials allude to loss, memory, and the displaying of this vicious cycle that continues to plague this society.

Campo Algodon, Cuidad Juarez, 21 de Febrero del 2007 (detail), 2011 site-specific installation. Rubbings of court documents (classified documents used in Human Rights International courts in Chile, defending the victims), acetone.

LMF: Are the materials corporeal stand-ins for you to some degree?

ACC: I feel that the materials are an extension of these victimized women. It’s as if they become echoed voices, engrained patterns, memories, and restored faiths. I collaborated with a tile company from Dolores Hidalgo, Mexico, to make tile body bag tags with the Juarez victims’ names using soil from the crime site. In Voces de Las Perdidas the tags cascade from the ceiling allowing the viewer to walk and be immersed in the many lives lost to these violent acts. It’s important that these works include information of real individuals, both found and missing, because it allows me to document these unjust social/political events in contemporary times. In a performance where I used the body bag tags again, I broke the tiled tags as a way to break that silence within myself but also for these voices that are no longer heard. As I broke the tiles, the sound became muffled and there was an actual resistance to the tile breaking. It was so difficult to be heard once you got to that last break. These works become my voice of protest. The silencing of this subject matter in our media headlines become as erased, as hidden and as forgotten as many of the victims are.

Quebrar el Silencio (Break the Silence), performance, 2011. Four hundred and fifty ceramic body bag tags, dimensions vary.

LMF: How do you navigate the tension between the specificity of the Juarez murders and the universality of violence and loss in general?

ACC: At the University of Texas during my MFA, I worked with professors from various departments to create a “working group.” Their purpose is to find a collaborative dialogue between art and human rights academics on subjects such as the femicidios. I have an urgency to explore other regions that are dealing with similar offenses. The law professor who provided me the classified documents invited me to a human rights conference, where it was noted this type of violence (femicidios) was not just in this one region, but universal. During the conference, attorneys, forensic scientists, and UN officials addressed how violent offenses can be similar but might be handled differently according to there standing laws.

LMF: There’s a strong element of impermanence to the work.

ACC: News of the Juarez Femicides hits mainstream media a lot and then it’s onto the next big thing. Each time I install the installation, Campo Algodón, I feel that it parallels these murders because it’s up, people see it, talk about it, and it has its moment of validity and then its as if it disappears, or in the installations case, it’s painted over. Almost recreating this vicious and endless cycle. The work is not specific to one place; it relocates itself. Many of the pieces in the series dematerialize by either decaying from the outdoor elements or from the actual physical materials itself.

Memento, site-specific installation, 2012. Victims’ names transferred on wall, ashes from burned paper list, dimensions vary.

The pieces with ash leave a trace. When I go into the spaces that they’ve been exhibited in, I love looking at the floor and seeing that there’s always a trace of footsteps.

LMF: Minimalism has pretty specific art historical and cultural connotations. How do you think about minimalism in your own work?

ACC: I like that in minimalism things are pristine and concise. A greater affect is achieved with the use of specific materiality that often masks the labor that goes into it.

With my late aunt being an anesthesiologist and my uncle who is a practicing cardio vascular and thoracic surgeon, I was often exposed to observing surgeries. Watching them work to prolong peoples’ lives had a strong effect on me. Viewing these procedures be completed and benefit the patient to a successful recovery, led me to understand the vital importance of a pristine and concise working atmosphere. My pieces have a coldness and these pieces depend on a sense of starkness: there is a distance between you and them, they are minimally quiet, dark and meticulous, and the cold contrast between black and white aims to invoke a sense of the unending conflict and chaos of light vs. dark, good vs. evil. For me, minimalism achieves a simple contrast to a complex effect. If you look at Donald Judd’s steel boxes in Marfa, there is such precision, and once you start to really study them, you realize that they are all constructed slightly different, hence the simple contrast to a complex effect.

LMF: How does religious ritual inform your work?

ACC: I come from a practicing Catholic family. If a family member passed away, it was our custom to gather as a family to encircle him/her with our presence, our love, and our grief. The majority of my installations coincide with a religious ritual by placing the object in the center of the space. I want this to give the viewer the opportunity to encircle and act out the same ritualistic motion, such as in the piece Madre (Mother). The work quietly takes the viewer through the stages of grief: mourning, anger, and hope. One victim’s mother said, “The one person that I feel like I can relate to is the Virgin Mary. She is a symbol of hope and strength, especially to someone who has lost their child in such a violent way.” I acquired hand picked cotton from the border region and embedded it in a resin mold of the Immaculate Conception. It was interesting because the cotton inadvertently landed in her head, heart, and stomach. Happy surprises that I find symbolic and keep me going.

Madre (Mother), installation, 2011. Resin, cotton, found object made of wood (pillar), dimensions vary.

Adriana Cristina Corral’s work was featured in David Shelton Gallery’s group show Under the Moontower, in Houston, which closed August 17. She is also featured in the Bellevue Arts Museum’s Outstanding Student Achievement in Contemporary Sculpture Award exhibition until September 22.