Lynn Barber lives in Rapid City, South Dakota. She has degrees in microbiology and law, and intermittently works as a patent attorney. She enjoys playing the hammer dulcimer and the concertina. She’s married to a shy guy named Dave, who holds advanced degrees in meteorology and theology. Both are members of the ACLU and are devoted to their dog, aptly named Maverick. They’re in their mid-late sixties. They don’t have a lot of money and what they have, they put into their passions. In Lynn’s case, that would be birds and birding.

Lynn has been a birder since she was 14, is a board member of the American Birding Association (ABA), past president of the Texas Ornithological Society and past president of the Fort Worth Audubon Society. Although birding began as a pursuit for gentlewomen, at its highest levels it has become a boys’ club—one in which Lynn is the only woman amongst 12 individuals to have seen more than 700 species during an ABA Big Year.

I met Lynn when we both lived in Fort Worth and Dave was the pastor of the little church I attended. What always struck me about her was her lively interest in all sorts of things—and her outspoken protest against things she didn’t like. As such, her absence for almost all of 2008 was conspicuous, but that was her ABA Big Year, which she wrote about in a book published in 2011.

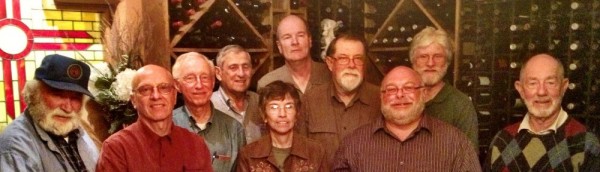

In early December 2012, 10 of 12 birders who’ve seen more than 700 species during their Big Years met in McAllen. L to R: Benton Basham, John Spahr, Bob Ake, Al Levantin, Lynn Barber, John Vanderpoel, Dan Sanders, Greg Miller, Chris Hitt, Sandy Komito. Photo: Greg Miller

Komito and John Vanderpoel have numbers slightly in excess of 740. But what makes Lynn’s Big Year special—apart from it marking another “first” for womankind—is the book she wrote about it. Published by Texas A&M University Press, Extreme Birder: One Woman’s Big Year is a straight-ahead, self-effacing account of birds improbably pursued and seen (and not seen), numerous phobias barely quelled, generous collegiality, more birds and other creatures, trekking under all weather conditions and over all kinds of terrain, sleep deprivation, going deeply into debt (a second-mortgage) and blissful descriptions of the natural world. Here and there, her prose is punctuated with doggerel. Below is a bit of rhyming that seems especially relevant to anyone involved in visual art. It is called Chickadee Meditation.

I could not see the forest for the trees,

Til I went north to seek chickadees.

Now the whole thing is clear, and sadly I fear,

That I’m killing myself by degrees.

There is something bizarre and absurd

About living one’s life just to bird.

There’s no rudder, no balance, no skills and no talents,

Yet this mania cannot be deterred.

Don’t ask if it makes any sense,

This big year, so driven, intense.

There’s no reason, no rhyme, for such use of my time,

And no justice in such an expense.

Lynn is good at photography (of birds) and painting (of birds). But those images focus on the object of her obsession. The art form, as it were, that the book drew me into is the act of birding. Or, as the case may be, reading about the act. I’ve gone on short birding excursions with Lynn on two occasions—once to see nesting herons by Lake Benbrook near Fort Worth and once to see some sort of owls down in the Hill Country—and while it was fun to see her in her element and, of course, to see those birds, I did not enjoy the standing around, squinting, shivering and waiting.

But Lynn’s book—the prose and the poetry—telegraphs her doggedness, self-doubt, mania and elation. It doesn’t directly engage with art, but it candidly talks about something very much akin to the excitement that comes with seeing something new in a painting or joining parts of a sculptural object. In the end, it tells us not to fret about what we do or why, but to surrender to it and focus on the joy in it.

All images and poetry are by Lynn Barber, unless otherwise noted, and are reproduced with her written permission.