[Ed note: This is the second profile in a series by Gene Fowler on Texas documentary photographers. The first, on Ben Tecumseh DeSoto, is here. The third, on Earlie Hudnall, is here.]

Downtown Houston was eerie and still the night that George Hixson stalked its streets in 1981. A 23 year-old from upstate New York, Hixson planned to head for California after visiting a friend in Texas’ largest city, and the seemingly dead and depressing atmosphere of Houston’s urban core made him want to flee sooner. And then… .

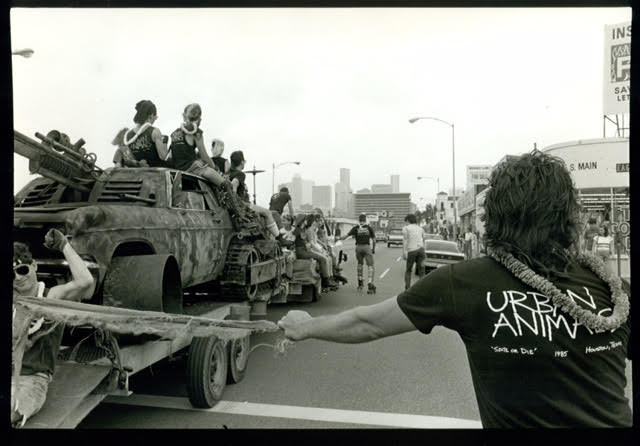

Sitting on a Smith Street curb, Hixson beheld a rolling mass of art squad energy careening toward and past him from out of the night. Skates. Hockey sticks. Dogs. Hollering. Howling. Wild as anything that ever raged in the West, the renegade cultural collective called the Urban Animals was an amazing sight. “I knew right then I had to find out what was really going on in this place. I had to stay right here. Never made it to California.” A few years later, Hixson photographed the Urban Animals when the group assisted French musician Jean-Michel Jarre with his mega-concert and visual spectacle Rendezvous Houston.

The high-profile Jarre piece aside, Hixson soon learned that, in those days, the raw and vital sector of Houston’s art scene percolated mostly under the surface. And it took some circulating to weave one’s way into the folds of its mysterious fabric. “Houston was so different. It was a different world. Riding the bus on Washington one night, I noticed the lights go off and the bus driver and riders lean low in their seats. We were passing a Jeep dealership with guys shooting at each other from either side. And that’s when I thought, ‘I’m really in Texas.’”

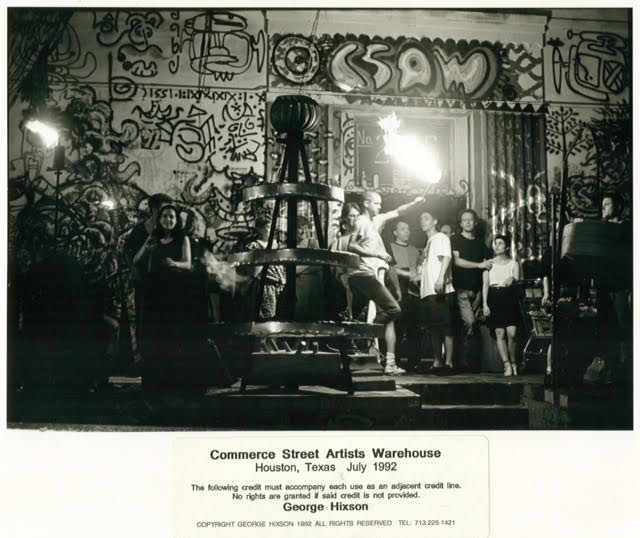

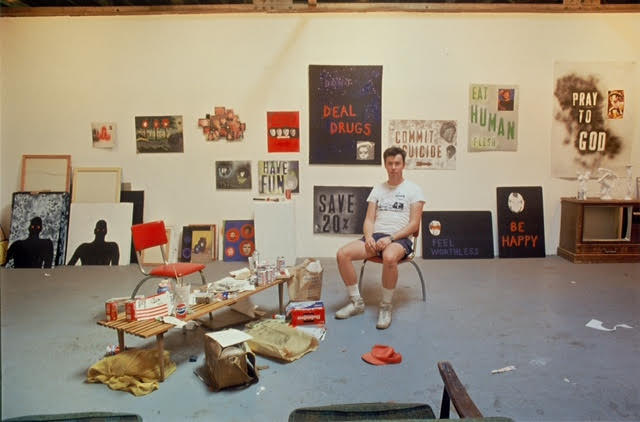

Before long, Hixson discovered the Commerce Street Artists Warehouse. Renting studio space in the former abandoned warehouse, he began to meet artists like Wes Hicks, Jim Pirtle, James Bettison, Deborah Moore, and Dr. Robert Campbell, the last of whom administered a tetanus shot when Hixson stepped on a warehouse nail. Having begun taking photographs in high school (“When I saw Robert Frank’s The Americans as a kid, I thought, ‘That’s what I want to do!’”), he documented the exploding music, performance, and art scene at the Warehouse, Lawndale Art Center, the Axiom, and other venues. Through the end of the 20th century and into the 21st, Hixson had his lens trained on much of Houston’s most interesting art. The fact that some 62 of his images were included in The Contemporary Arts Museum Houston’s 2009 survey of the city’s artists, No Zoning, indicates the central role he performed in documenting important local work.

Hixson describes a photograph of Jim Pirtle painting at an easel as an uncharacteristically “staid” image of the artist. “Jim was painting a series of portraits on polyester shirts stretched on canvas frames,” he explained. “But I also remember a performance in which Jim wore a diaper, riding in a baby carriage, with Bettison in drag. I thought if I didn’t photograph it, no one would believe it.” (Haven’t seen the photo, but I sure as heck believe it.)

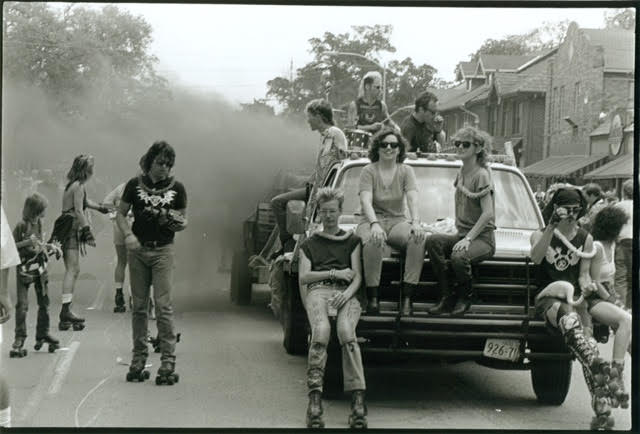

Hixson took to roller skates in 1986 to photograph a gonzo parade of floats, vehicles, a marching band, and other mobile what-is-its that ‘cacophonied’ down Montrose as a side event to the annual New Music America festival, which was held that year at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston and brought John Cage and other composers to town. Featuring what the photographer describes as an Urban Animals ghetto-blaster tank (pictured at top), the joyous stroll and roll helped inspire the founding of the annual Art Car Parade just two years later. In 2016, Hixson’s own art car, Metacarskull, won Best Art Car in the parade.

In another large transportation-themed piece, Hixson rode along to document Nestor Topchy’s 1995 Zocalo Mobile Village bus trip of ten or so artists, described by Houston Press writer Brad Tyer as a gaggle of “performance characters” with “touchy, helium-filled egos,” on an art-presenting trip to the nation’s capital and further northeast. The photographer mentions one especially hairy Topchy traffic maneuver that left the crew upside down and checking their innards. “But the poet Malcolm McDonald was sitting at a table in the bus, calmly writing,” Hixson recalls. “When we asked what he was doing, he replied, ‘I’m making out my will.’” (Some on the bus may have been ready for the poet’s departure. Tyer reported that McDonald, “who once chased a small after-hours crowd around [Houston venue] Catal HYyYk with his whizzing penis in his hand after an argument over $5, insists on challenging every personality characteristic of every member of the entourage, just to see if he can make them cry.”)

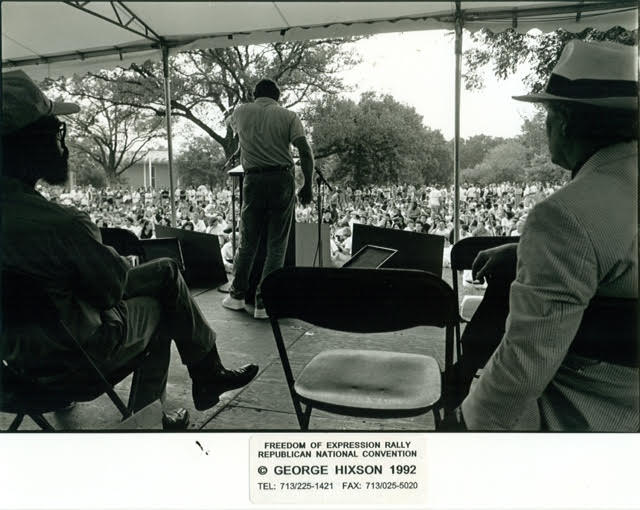

George Hixson’s photo of a protest rally during the 1992 Republican National Convention held in Houston

Fun times, yes, but it all brings to mind the age-old question of whether one was remaking the world anew, reinventing the “barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world,” or if it was merely the fresh, buoyant rush and allure of youth. And as the mystic Beatle instructed, “All things must pass.” Hixson still documents the occasional cultural moment, but it’s different now. “Now that everything is digital,” he explains, “and lighters are cell phones, everything gets documented a thousand times over. I find myself documenting the documenting.” Still, he maintains that his work is documentary by definition. “Most documentarians are on the outside looking in. I’ve always felt like I was on the inside looking around. To see what’s behind the shadows, the curtain, things that go unnoticed. I’m compelled to look for and document things that are off the radar.”

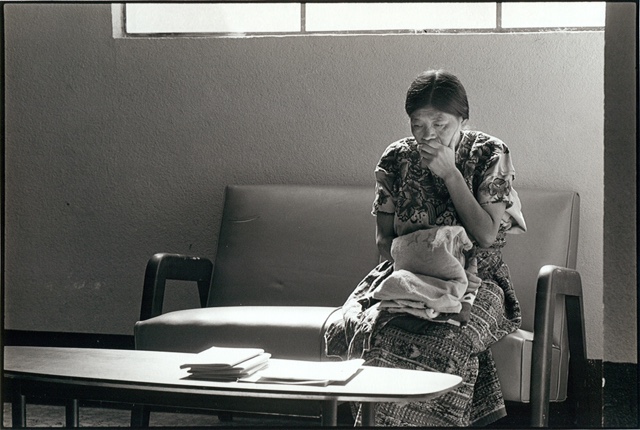

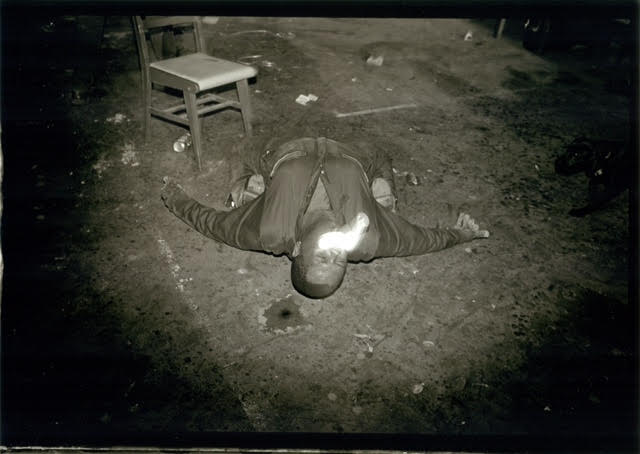

One of Hixson’s images from the waiting room of the clinic the artist Dr. Robert Campbell built in Guatemala.

Dr. Robert Campbell was way off the radar and in the best way possible. The artist-physician established clinics for poverty-stricken refugees in Central America, continuing the work even as AIDS wracked his own mortal frame. Hixson was one of many Houston friends who answered the call to fly down to Guatemala and assist in the effort, working on the clinic’s electric and plumbing systems and making powerful portraits of the clinic’s patients. Before Campbell’s death in 1995, the photographer also assisted with his final exhibition, Tierra de Vida (Land of Life), at DiverseWorks. Michael Berryhill’s account of Robert Campbell’s life and funeral in his hometown of Claude, Texas is an illuminating read.

No matter what, of course, there’s always that pesky issue of paying the bills. When he first arrived in Houston, Hixson found work tending bar. But he soon took a photographer job with the University of Houston, working on the school’s publications. “I also worked for Public News during that time,” he recalls. “I went to the office and met the editor Richard Tomcala. He said, ‘Here, take out the trash and you can be our photographer.’ It was the best thing that happened to me. They sent me to events and shows I would never have gone to on my own.” He made images for Public News until the paper closed in 1997 and then worked for a time with the Houston Press.

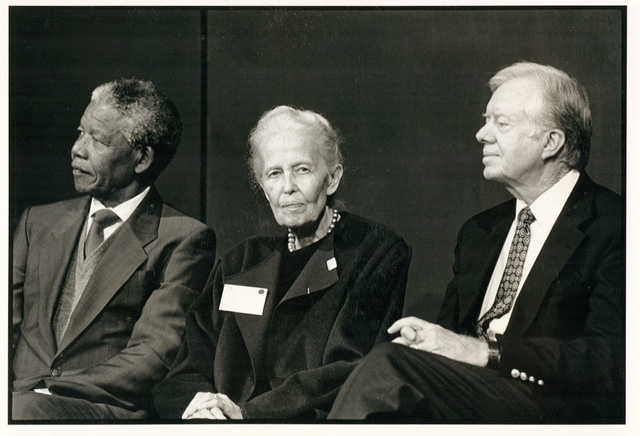

George Hixson: Nelson Mandela, Dominique de Menil, Jimmy Carter at the Rothko Chapel, 1991, on the occasion of Nelson Mandela receiving the Carter-Menil Human Rights Award

At some point, Hixson transitioned to freelancing and found work photographing art for the Menil, Contemporary Arts Museum, and other Houston institutions. In one of his favorite memories, he sat on the floor of the Rothko Chapel in 1991 to photograph the occasion as former President Jimmy Carter and Dominique de Menil presented Nelson Mandela with the Carter-Menil Human Rights Award.

George Hixson: Walter Hopps, artists, and friends on the occasion of the inaugural Walter Hopps Curatorial Award

A decade later, in what has to be something of another career highlight, Hixson found himself in Nancy Kienholz’s Houston studio photographing a remarkable assemblage gathered to commemorate the inaugural Walter Hopps Curatorial Award. The group portrait, which appears in the documentary film about Hopps’ Ferus Gallery, The Cool School, includes Hopps, Robert Rauschenberg, Ed Ruscha, Caroline Huber, Ed Moses, Dennis Hopper, Sharon Kopriva, James Rosenquist, Terry Allen, James Surls, and others. Hixson first met the mysterious curator after Hopps phoned him one night at 1 a.m. “He immediately started talking about an L.A. murder, then an art piece, crazy stuff, before he said, ‘This is Walter Hopps,’ and asked if I’d photographed a certain piece at the Blaffer four years earlier. I said yes. He said, ‘Can you photograph a Joseph Cornel piece for me?’ I asked when and he said, ‘Right now.’ So I did. We had a bite to eat, and then we were up all night. That was Walter.”

The No Zoning catalog text informs that, although Hixson holds a degree in photography and film from the University of Bridgeport, “he got his ‘real art education’ among the artists at Commerce Street Artists Warehouse.” In 1990 he even blew up the art collective’s toilet with his own performance piece, Paint Bomb. “Houston’s cultural landmarks and topography change constantly,” the catalog observes, “and so does its underground scene. In a city that saves so little history, Hixson’s archive is a black-and-white treasure trove of the people, places, events, and everyday life in Houston during an especially energetic period.”

6 comments

wow…just amazing

George is a genius and one of the best photographers ever, hands down. What an eye!

I agree!

Nice work, as usual Gene. Thank you.

The New Music America Festival that was held in 1986 was not presented by the Museum of Fine Arts. It was organized by Michael Galbreth and hosted by a myriad of arts organizations with DiverseWorks being one of the main organizers.

John Cage’s work was presented in the HMFA sculpture garden and other works were apparently presented throughout the city, including, interestingly, at the Astrodome. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/style/1986/04/13/brave-new-sounds/f797a1c3-71af-49f1-8541-8c67ba57f2c1/