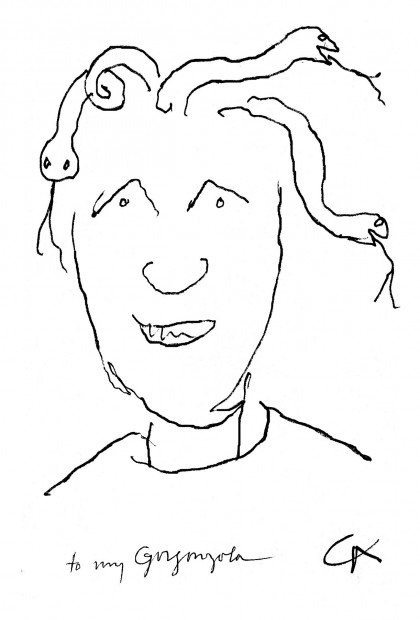

Alexander Calder

Sketch caricature of Dominique de Menil, 1964 (c) 2012 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Menil Archives, Manuscript Collection

In celebration of the Menil Collection’s twenty-fifth anniversary, the museum has mined its archives to produce Dear John and Dominique. Curator Michelle White and archivist Geraldine Aramanda have gathered a thoughtful collection of letters written to John and Dominique de Menil accompanied by ephemera, photographs and art objects. With low lighting, available seating and a wealth of interesting material, the exhibition space functions as a quiet, inviting reading room.

The correspondence on view—exchanges between the couple and the artists, architects and activists whose work they supported—evidences the de Menils’ role as facilitators. Installed over four cases, and thus divided into four groupings (roughly: activism, exhibitions, art, architecture), the divisions are anything but distinct. Instead the porous categories and thematic slippage speak to the de Menils’ concentrated vision and their belief in the power of visual culture to elicit both spiritual and real change.

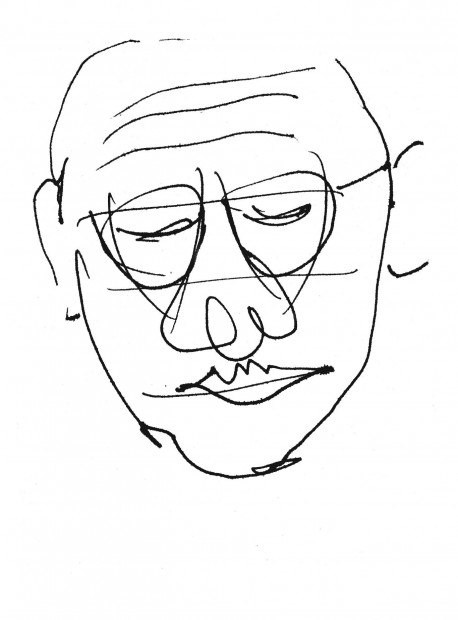

Alexander Calder

Sketch caricature of John de Menil, 1959 (c) 2012 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Menil Archives, Manuscript Collection

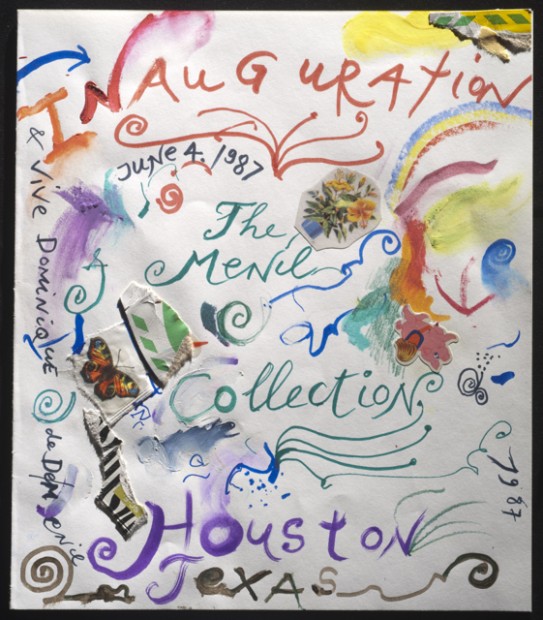

The architectural case traces the de Menils’ collecting activity in built form. It ranges from the commission of multiple satellite galleries to the 1987 inauguration of The Menil Collection (the handmade gallery maquettes are a playful highlight). Not only does the case feature some of the most prominent figures of modern architecture—Philip Johnson, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Louis Kahn—it testifies to the de Menils’ role as active patrons. In particular, a 1962 reply from Johnson offers one side of a critical dialogue between John and the architect. Here, we read Johnson’s response to several comments regarding his past building projects. One wonders the full content of John’s original critique (the exhibition only features letters written to one or both of the de Menils).

The vitrine also presents the wide-ranging reverberations of the de Menils’ architectural projects, from James Johnson Sweeney’s profile of the Johnson-designed de Menil house in a 1966 “Vogue” to a 1997 letter from the archbishop of Cyprus regarding the Turkish occupation. A 1989 dispatch from Dominique to her son/architect Francois, in which she recounts her struggles concerning the proper housing for the Cypriot frescos, presents a refreshing sense of humility:

The plans we have developed have been justly criticized: without being an exact replica of the Lysi chapel they are reminiscent of it, and it has been argued that it would smack of “Disneyland.”

It was my intention to reconstruct in Houston a chapel similar to the one from which the frescoes had been ripped off. I thought this would be the best way to do justice to the frescoes. Obviously it is not the best way to look at them.

It also illuminates her curatorial philosophy. She shows disdain for a traditional museological display “[which] leaves out an intangible element, different to weigh and express, yet very real. It leaves out their spiritual importance, and betrays their original significance.” And she connects this consideration of the artifact as both an art object and a religious relic to the Rothko Chapel. Yet curiously, she dismisses the need to display “the original significance” of the African artifacts because they “Belong to a culture that does not exist in America.” Dominique’s curatorial perspective, it seems, stems not from pedagogy or aesthetics but from a desire for a personal and idiosyncratic spiritual communion.

James Lee Byars: Letter to Mrs. de Menil, 1990,12 banana leaves and gold ink, Copyright the Estate of James Lee Byars, The Menil Collection, Houston, Photo: Paul Hester

The enactment and impact of this curatorial philosophy is taken up in the exhibition’s central two cases, one devoted to display of artists’ letters, the other relating more specifically to exhibition practices. Ranging from the humorous to the intricately illustrated, the artists’ letters give waste to the notion of the post as obsolete or passé. James Lee Byars’ contribution is perhaps the sexiest: 12 large banana leaves inscribed in gold ink, the script ornamented with stars and nearly illegible in its florid detail. A favorite on view is Jim Love’s (long) note of encouragement to Dominique:

In certain isolated and quite rare cases, people whose own lives and intellectual curiosities are of sufficient substance as to be worth legitimate inquiry, and thus do themselves provoke the intellectual curiosity of others, have somehow added some remote and haunting something to the art that they have acquired.

I sometimes feel that a work of art which is made of good honest stuff and thus is worth its salt, sort of has a right to feelings. This is in a sense like a person who has a home—where it is the best place to hide, the easiest place in which to collect his thoughts, and where it is most comfortable to go to the bathroom.

Certain owners add a bit of poetry to the groups of things they have rounded up.

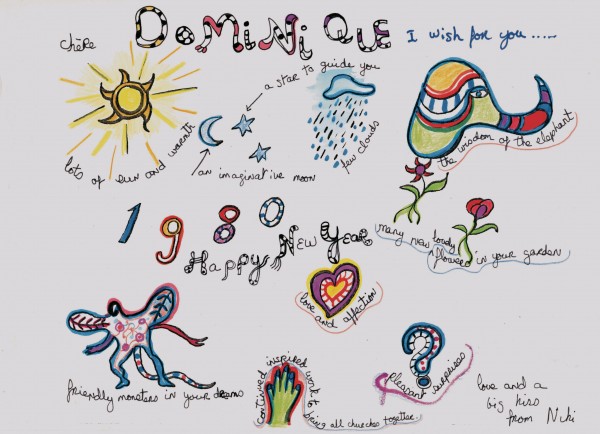

As a corollary to the vitrine, a selection of artists’ letters is also displayed on the walls, including a lovely suite of collages by Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely. Roberto Matta fantastically reimagines the de Menils’ New York townhouse as a confluence of interior and courtyard views. Specific works from the de Menils’ collection are visible—a Mondrian grid, a Picasso portrait, what looks like Max Ernst’s Moonmad—alongside his characteristic amorphous figures. The cross section drawing recalls the illustrations accompanying his 1938 “Minotaur” article “Mathématique Sensible—Architecture du Temps,” a Surrealist rejection of Le Corbusier’s mathématique raisonnable; while Matta’s earlier essay was an attack on modernist rationalism, here a tradition-bound Upper East Side townhouse undergoes a playful architectural transformation. The de Menils’ sense of humor is also on view in the two Calder caricatures; one featuring Dominique as a snake-haired Gorgon and inscribed “to my Gorgonzola.”

Victor Brauner, New Year’s greeting from artist Victor Brauner, 1957 (c) 2012, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris Menil Archives, Manuscript Collection

In contrast to the exuberance of the artists’ letters, the exhibition and display missives are more business-oriented. The case begins with a number of items relating to Andy Warhol and his 1968 visit to the University of St. Thomas, including two small portraits by the artist, one of Dominique, the other of Mao Tse Tung. It also features the two figures most responsible for shaping the de Menil’s collecting and curatorial practices: the Dominican friar Marie-Allen Couturier and the curator Jermayne MacAgy. The correspondence between MacAgy and Dominique center on exhibition planning; this theme continues after MacAgy’s death with Dominique’s organization of the memorial exhibition and publication Jermayne MacAgy: A Life Illustrated by an Exhibition (November 1968 – January 1969) at the University of St. Thomas.

Perhaps the most surprising case contains the letters relating to the de Menils’ community involvement, revealing John’s work with the SHAPE (Self Help for African People through Education) centers and his support of Mickey Leland’s political career. The invitation to the de Menils’ house to celebrate Leland’s congressional run in 1978 must have sent shock waves through the neighborhood when little over a decade earlier, the city was still enforcing Jim Crow laws. It also contains the most stunning item in the entire exhibition: artist Larry Rivers’ musings to John, written in April of 1970, regarding his upcoming installation Some American History.

Niki de Saint Phalle, New Year’s Greeting, 1979, (c) 2012 Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All rights reserved / ARS, NY / ADAGP, Paris The Menil Collection, Houston, gift of the artist

Photo: Janet Woodard, Houston

Commissioned by the de Menils and presented at Rice University’s Institute for the Arts, Some American History was a collaborative installation under (white) artist Rivers’ direction in consultation with (black) artists Ellsworth Ausby, Peter Bradley, Frank Bowling, Daniel LaRue Johnson, Joe Overstreet and William T. Williams (February 4 – April 25, 1971). Rivers’ letter relates his desire to lend the project authenticity, and his resulting struggle to convince local black artists to join the project, complete with an unfortunate mimicry of a plantation dialect. The exhibition was meant to be a visual documentation of black history in America, from slavery to the present, the centerpiece of which was the life-size construction of a lynching, Caucasian Woman Sprawled on a Bed and Eight Figures of Hanged Men on Four Rectangular Boxes. This was a story Rivers felt particularly apt to tell:

You know when I went to Africa in ’67 to make a film. I felt the same eagerness to become involved in a work about Black People. Now as then I thought I was especially equipped for the task. Why…. Some as yet unfigured out notion that my life and my sense of a Black person life in these United States its peculiar tragedies its exhilarating specialties & ironies put me in a position to see hear & feel more than most white people & that there resides in me some essential talent to be able to act upon it all….

Unfortunately, this sentiment was not shared. The exhibition elicited national criticism as well as dissatisfaction from the participating artists. Indeed, Rivers’ understatement to John is applicable to the project as a whole: “You and I began all this in innocence.”

Victor Brauner, New Year’s greeting from artist Victor Brauner, 1957 (c) 2012, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris Menil Archives, Manuscript Collection

In response to the backlash Some American History generated, the de Menils proposed a radical exhibition partnership with the Black Panthers, which resulted in one of the first racially integrated exhibitions in the country. Held at the De Luxe Theater in Houston’s impoverished fifth ward, the De Luxe Show (August 22 – September 29, 1971) brought to town exhibiting artists such as Peter Bradley, Sam Gilliam, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski and William T. Williams as well as the most prominent critic of the period, Clement Greenberg. Smartly, White and Aramanda do not lay this material out chronologically; the cause and effect between the two exhibitions is not obvious but the dots are there to be connected.

As a whole, Dear John and Dominique provides evidentiary support for much of what we already know of the de Menils—but what interesting evidence it is! The variety of correspondence, from the casual to the considered, from the playful to the practical, demonstrates the depth of their working relationships and their seriousness as patrons. This studied collection of archival material offers a unique glimpse into the heady environment the de Menils cultivated in Houston.

Dear John & Dominique: Letters and Drawings from the Menil Archives

The Menil Collection

August 10, 2012 – January 6, 2013

______________

Elliott Zooey Martin is an art advisor in Houston..