Galerie Frank Elbaz opened in Dallas in the fall of 2016, just in time for one of the city’s two hefty art months. (In Dallas, these months are April, due mostly to the Dallas Art Fair, and October, due mostly to the annual Dallas Museum of Art-Rachofsky gala). The design district space is an outpost of the gallery of the same name based in Paris since 2007. When it opened here, word on the street was that it was meant to be a temporary experiment by its namesake owner, who on trips to Dallas had identified a city that may be ready to embrace the program’s quiet, intellectual, blue-chip disposition.

Two years on and it’s still mounting surprising shows that follow a much more international (and mega-gallery) trend of showing museum-quality work that, while technically for sale, doesn’t seem to need to be sold. And while the gallery has occasionally dipped into the Texas scene, showing recognizable names like Mark Flood and Andy Coolquitt, the gallery is mostly associated with showing older or dead international post-World War II artists who deal in abstraction and come with a certain pedigree: Sheila Hicks, Julije Knifer, Martin Barré. Right now in the art world, there’s a lot of reassessment going on of the work of artists who were appreciated in their working prime, especially by their peers, but who didn’t sustain much traction afterward, despite the work being quite good to very good. Elbaz traffics in some of this trend, albeit on a modest scale. The solo and group shows at Elbaz’s Dallas outpost have often been curated by Paul Galvez, an art historian and research fellow at the University of Texas at Dallas.

The show that’s up now (and closes after this weekend) is work by Jay DeFeo, a San Francisco-based artist who was associated with the Beat Generation and died in 1989. It’s a terrific show, and feels like a private walk-through of the artist’s own sketchbook. The Whitney held a retrospective of DeFeo’s work in 2013, and there was a fair amount of press about it, and especially about the piece she’s most famous for, which is an enormous painting titled The Rose that weighs more than a ton and took the artist eight years to complete. (The Whitney owns it.) But the show at Frank Elbaz, organized with the cooperation of DeFeo’s estate, is titled Object Lessons, and it’s works on paper from the 1970s.

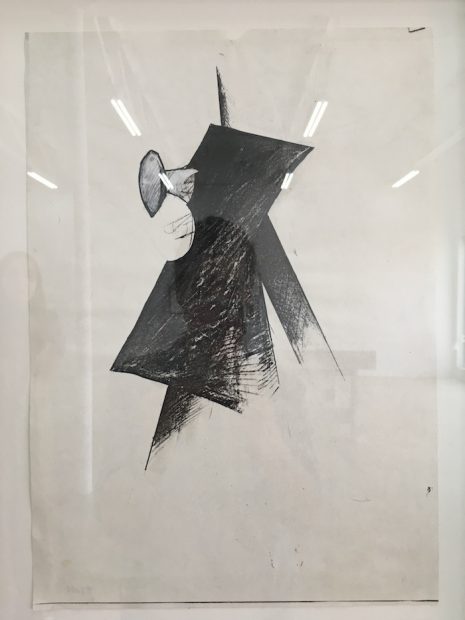

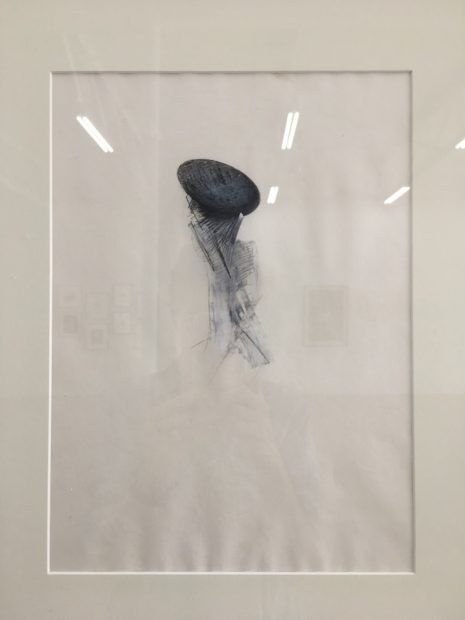

I have to admit that there’s a real comfort in confronting work for the first time that so clearly belongs to a recognizable and distinguished era, or scene, or movement, with a set of reference points that are already seared into your brain. It takes a couple of decades of looking at art to get into this consistent groove, but while I missed DeFeo’s Whitney show, the works on paper at Frank Elbaz were as familiar to me as, say, a Kinks album I had somehow missed the first time around. I liked the show immediately. The drawings are bursting with quiet authority and charisma, and backed up by a clear and obsessive deliberateness: during this time, DeFeo was determined to capture and recapture certain objects in her studio — a compass, a tripod — in all their banal-yet-oddly anthropomorphic objecthood.

For me, the most obvious corollary with this work is the muscular drawings of Lee Lozano, and the repetitive studies of objects by Jasper Johns, though this is oversimplifying matters: DeFeo is her own animal, making forays into surrealism and multi-point perspective with a deftness that makes me rethink the wonders of graphite. She has an incredible way with composition and movement and texture (Picabia and Duchamp are the obvious touchpoints here), and these works come off like careful portraits drawn by an artist who fixates on her subject while remaining distant and coolly objective about it. Most of the drawings are really good, and few of them are downright great. DeFeo was beloved by the other artists in her West Coast scene, and in these drawings you can see why: there’s nothing flip, easy, or lazy in the work, even when it comes off as fast and gestural. These works show an artist at the top of her game.

Jay DeFeo, Untitled (Tripod series), 1976. Graphite and acrylic on photocopy, cut to the outline of the figure and laid down on paper

And while Lee Lozano’s bonkers (and cathartic) aggression isn’t in this work, a thorough reckoning is: in the end you get the sense that no one on earth knows the DNA of a wooden tripod better than DeFeo. If this sounds silly to you, I’d suggest that you’ve maybe missed the whole boat on what artists are about or how or why they make the work they do. For DeFeo, the tripod itself is beside the point, because the point is the deep dive and total ownership of a subject, which in this case happens to be an object, a tripod — one that offered up exactly what DeFeo needed at the time to work through her aesthetic concerns. From now on (and though DeFeo avoided straight figuration) I’ll never use a tripod without thinking, affectionally, of DeFeo.

Galvez, as curator of the show, presumably had a lot of work to choose from considering DeFeo’s ultra-prolific output, and the selection and groupings of drawings here are well-calibrated: there’s plenty to get your head around but not so much as to overwhelm. Most of the works are graphite or graphite-based — elegant and finespun — though DeFeo was certainly of her era in switching up modes and mediums: there are images of tripods and compasses here that are photographed and Xeroxed, collaged, and painted. There’s a display table too, with photos and ephemera from DeFeo’s studio, but that almost feels like an explanation or apology for anyone coming in off the street who can’t suss the premise of the show (or the gallery itself). It’s lost and flat amongst the actual drawings. This doesn’t matter to anyone who just wants to see the show, but in a way, it’s also telling. It’s difficult to know what the fate of a space like this has in a place like Dallas. While the wealthiest galleries, in New York and London especially, have increasingly taken on the role of museums in organizing ultra-authoritative shows by some of the great celebrated and under-sung artists of the last century (some of the most memorable ‘museum’ shows I’ve ever seen — of de Kooning, of Manzoni, of Albers— have been in commercial spaces like Gagosian and Zwirner), Galerie Frank Elbaz has brought some of that trend to Dallas, at what we can only assume is great expense. Keep an eye on it while it’s here.

‘Object Lessons: Jay DeFeo Works on Paper from the 1970s’ is at Galerie Frank Elbaz in Dallas through July 14, 2018.

2 comments

Well said!

Thank you, Christina. Wonderful and so very true review of that show. I went the opening and loved those works on paper. SMART comes to my mind, and also RESTRAINED. Your words are better.

I hope they stay in Dallas. They bring much needed variety here. And artists that we likely would never see…

At least I wouldn’t.

Dan