The most important task the drawing instructor must undertake for his fundamentals student, if that student is to be successful, is convince him that he lives in a three-dimensional world. Although the student continues to breathe air, his consciousness of the world—which in earlier times was formed by physical labor like planting a seed or writing with a pen—has begun to inhabit a two-dimensional world: first of the television, and now the computer screen.

A computer in itself is a three-dimensional object and while the information seized through it is infinitely dimensional, the screen upon which the user gazes is a surface with length and breadth but no depth. The drawing instructor’s students have entered into this surface in a profound way. If the printing press stole the story from the storyteller’s mouth and hid it between the pages of a book, the drawing student has been seduced out of his hand by the siren song of the virtual.

Mermaids are about humanity’s primal wish to escape its earthly existence and the danger inherent in that longing. Every age has its siren song promising to bring the student one mile closer to his ultimate home: immortality. Fire, the wheeled wagon, the pages of the book, and the wings of the airplane have allowed him to build his tower from the bottom of the sea to the surface of Mars. Each of these steps on this ladder to immortality is one more step away from what defines him: a deep consciousness of inevitable death. The physical process of drawing by hand from a three-dimensional model resurrects this awareness of death.

Disconnected from his physical existence, the drawing student is anxious and afraid to look closely at the still life arranged on the pedestal, seeing in it the objective world he lives in but ignores more and more as his understanding of reality becomes reliant upon the phantoms of the mind embodied in binary code. His ancient antipathy toward the limitations of his own body has allowed him to see the screen as a trap door out of it.

Each digital innovation makes the student’s physical interaction with his surroundings more obsolete. Boarding passes no longer need to be produced, bent, wrinkled and stained with beer and grease at the airline gate. The scanable code on the screen of the phone erases the objective evidence, imprinted on a ticket, of a young couple’s last night in a strange city. Where will these travelers’ memories, wrapped in the Rorschach of those stains, now reside? Will they find new homes in the cloud, or will they float away?

The rapid loss of a thousand years of collectively acquired manual dexterity—now of so little use in the transformation of millions of small muscle movements into the monotonous pounding of the mouse—causes the drawing student to experience existential panic when he picks up a piece of charred wood and stands before a skeleton and a sheet of paper.

The greatest danger for the drawing fundamentals student lies in his inability to look at the object he is drawing. He looks away for a moment, forgets the object exists, and still moving his pencil but forgetting to breathe, slips comfortably down into the warm water of the imaginary. If he can resist the call to the bottom and turn his eyes toward dry land and take a breath, he can draw. The ability is still there, in the folds of his brain, encoded in a 16,000 year-old human memory borne in the drawings of the first draughtsmen at Lascaux.

The tragedy for the drawing student who cannot reach that other shore is his inability to see. Blind, he cannot translate vision into form. He is the student for whom the instructor has the greatest resentment and deepest empathy. His sighs and nervous shifting at the easel remind the instructor that for most, fear is stronger than the will to create. The student’s fear of failure is too great as he puts his tools away in a box and leaves the studio, convinced that images are not his to create. To the drawing instructor, his evacuation feels like a death, like one more casualty.

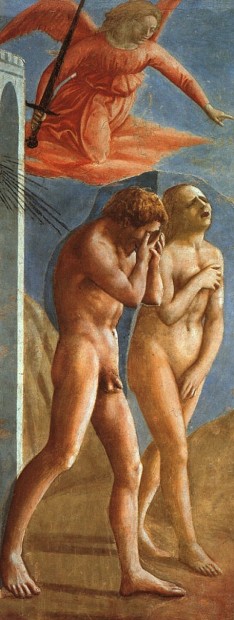

There are few things strong enough to bring the living into communication with the dead: illness, pain, the death of a parent. When the drawing student binds his eyes and hands together to reproduce a piece of the world, he creates an object that has the potential to survive after he is dead. Because of this he develops the unconscious awareness that he will die. This implicit awareness is made explicit in the drawing fundamentals syllabus. The semester begins with mark making, developing vocabulary and the potential to communicate. These marks are first used to describe themselves; a line is straight or curves into itself to become a circle. The symbols are then used to describe the inanimate objects in a still life, a skeleton, and finally, a living naked human being.

When the human model is at last facing the student, the introduction to the fundamentals of the objective world and its inevitable decay is complete. In the model the student confronts himself in the form of another human being: his living reflection. Closely observing each curve, wrinkle and hair of the model as he traces them with his pencil, the drawing student is confronted with himself; that thing he tries to avoid each time he looks away from it in the mirror. One day he looks into the mirror and sees an old face where yesterday a young one looked out not because time flies, but because he cannot bear to watch himself grow old.

The drawing student who looks closely and creates an image of himself in the form of the living model—using nothing but his eyes, his hand, and a pencil—stares back at the physical world that demands his death and recreates it through the power of his will. He resists the voices from the creatures on the rocks promising immortality, and thus overcomes his mortality, not in a dark escape through the net to the floor of the ocean, but in the acceptance that his life is short. Seeing just a few years drifting on the water between his boat and the horizon, he steers away from the reef and toward the home abandoned long ago by the family of man.

7 comments

Word! Looking without seeing. Most watch the world like a sitcom. Artists must SEE the world as an active and intimate process— not a passive one.

I enjoyed reading this! Charcoal is also frightening to students of today. Maybe the dead trees trigger subconscious links to the past.

I always love it when a student tells me, “I see everything different now, all the time!” It’s like they’re waking up.

This is beautifully written. Thank you.

This was such a beautifully written article, and speaks truth!

A universe of male pupils also filled the Academy under LeBrun’s guidance. Embracing with energy, relevance and perception tools at our disposal might provide a means to make creative and reflective works of art. I recall pointless fears about mirrors, cameras, photocopy machines, video cameras and more. Bise continues his appeals (generously laced with 19th century prose) to artistic and theoretical conservatism, perhaps appropriately so in this “red” state of Texas.

what’s Glasstire doing posting such eloquence? I thought they only did top 5 fashion moments du jour anymore.