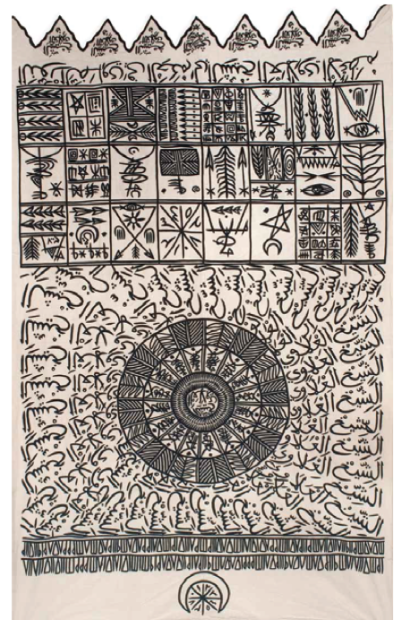

Rachid Koraichi, Les Maitres Invisibles (The Invisible Masters), 2008

Algerian-born Rashid Koraïchi created Les Maîtres Invisibles, a series of large black and white banners, using an appliqué technique with its origins in Pharaonic Egypt, and their markings appear just as mysterious and ancient. Five of his ninety-nine banners, covered with indecipherable script and arcane designs, are a focal point of The Jameel Prize: Art Inspired by Islamic Tradition, now on view at the San Antonio Museum of Art.

The £25,000 Jameel Prize, which Koraïchi won in 2011, is awarded every two years to a contemporary artist or designer inspired by Islamic art traditions. The current exhibition features the ten finalists from the 2011 competition: Noor Ali Chagani, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Bita Ghezelayagh, Babak Golkar, Hayv Kahraman, Aisha Khalid, Rachid Koraïchi, Hazem El Mestikawy, Hadieh Shafie and Soody Sharifi. The international biennial exhibit is organized by The Abdul Latif Jameel Community Initiatives (ALJCI) in partnership with the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London, which has the world’s largest collection of items from the Islamic Middle East.

Most banners function in a celebratory or ritualistic setting, but Koraïchi’s purpose is hard to determine. There’s no clue to the type of occasion, happy or sad, where these banners might be used. According to Tim Stanley, senior curator of the Asia Department at the V&A, they purposefully do not have any literal, translatable meaning. Their obscurity acts as a protective shield; to shut the viewer out of its meaning is to keep one from having power over it, creating a literal embodiment of knowledge as power. The banners’ willfully indecipherable script teases the viewer; any attempt to decipher their meaning is shunted aside by their size and intricacy.

In a gallery talk, Stanley explained the banners’ relation to Sufism and white magic. White magic, as opposed to black magic, offers protection and attempts to manipulate God and his love for the power of good. Stanley recognized that some of the banners’ imagery came from the tradition of antique Middle Eastern locks, which are themselves designed with complicated, nonsensical symbols that open when aligned correctly.

These banners and the white magic they enact stand as metaphors for the entire exhibition and its goals. For example, the illegibility and complexity of Koraïchi’s symbols suggest the western perception of Islam today: without education and awareness, we are locked out of understanding. Knowledge is a very different kind of power than the brute force of violence or the offense of torture, which are the power exchanges we normally hear about. The power of insight offered by the art in this exhibit is quiet but deeply effective.

Internationally renowned architect Zaha Hadid is performing a kind of white magic with her patronage of this prize, which aims “to explore the relationship between Islamic traditions of art, craft, design and contemporary work as part of a wider debate about Islamic culture and its role today.” The ten finalists for the Jameel Prize are international contemporary artists who use the power of visual art to transcend nationalities and politics. These alternative worldviews show Islamic culture not as one behemoth, homogenized set of ideas, but as various individual relationships with the artist’s spirituality and origins.

Bita Ghezelayagh, Felt Memories III, 2008/2009

The most impactful art involves intense artistic labor. Felt Memories III (2008-9) are talismanic wool felt shirts by Bita Ghezelayagh. They stand as symbols of her memories from the Iran-Iraq war. She adorns them with a thousand and one metal keys, tulips and crowns. The image of war hero Hossein Kharrazi is printed on multiple charms sewn all over some of the shirts, which become emblematic of resistance, protection, and martyrdom.

What appears to be a traditional black shawl with gold paisley patterns becomes an astonishing symbol of pain in Aisha Khalid’s Kashmiri Shawl (2011). From the front, the shawl appears to be an alluring, beautiful textile but upon closer examination, the gold dots are not tiny stitches but instead pins, their sharp lengths revealed on the back of the textile. Khalid uses this as a metaphor to explain how the Kashmiri people’s suffering goes unseen.

Noor Ali Chagani, Life Line, 2009

Other pieces involve intense repetition. Noor Ali Chagani, from Pakistan, uses miniature bricks in his work, which can be seen as an architectural relic of man, a timeless symbol for shelter, and as one part of a whole. In Life Line (2009), Chagani cast and molded mini terracotta fired bricks, each with two holes inside that he uses to string them together. The mini bricks are connected horizontally and vertically so they could look like a brick wall if they were laid flat, but because they are strung together, they are a flexible, textile-like expanse that Chagani drapes on the ground.

Hadieh Shafie, 22500 Pages, 2011

At first, the wall pieces by Hadieh Shafie appear to be an elaborate range of colorful paper circles assembled to create a formally beautiful piece. But 22,500 Pages is actually scroll upon scroll of printed and handwritten Farsi text bearing the message of love in a mystical, Sufi context. The very act of producing these scrolls, writing, rolling and ordering them into the art is a spiritual practice that she believes brings her closer to God.

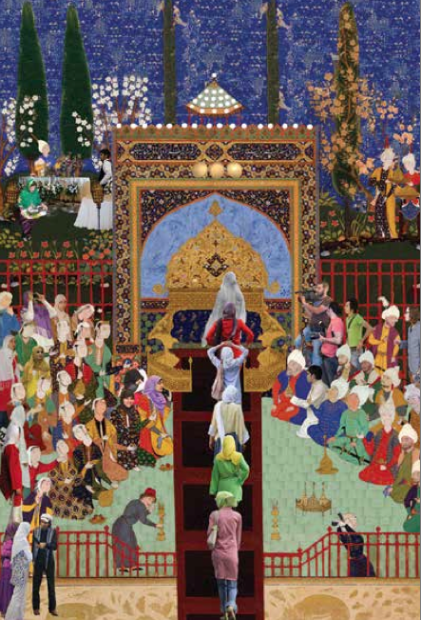

Soody Sharifi, Fashion Week, 2010

While none of the art appears subversive, all of it challenges stereotypical notions of Islamic culture. Though Houston artist Soody Sharifi’s photo collages deal with the role of women and Islam, she does so in a humorous manner. She blows up Persian miniature paintings to a large scale and inserts contemporary photographic representations into these historic scenes. The result is a seamless, but surprising juxtaposition of past and present. Fashion Week transforms a traditional palatial scene into a runway as six women in colored hijabs saunter proudly up the catwalk with their purses. We can only see their backs, but they don’t appear humbled or oppressed. They stand as reminders that their relationship with their religion is negotiable, an idea that gets overshadowed by the fundamentalist rhetoric we hear so much about.

Babak Golkar’s Negotiating the Space for Possible Coexistences No. 5 (2011) deals with the Islamic tradition of geometric designs and architecture. Golkar looks through hundreds of carpets to discover geometric designs that he then builds into three-dimensional models. These white shapes come up out of the carpets like high-rise buildings, creating a futuristic element that bears an uncanny resemblance to the Dubai skyscape, a prescient hint of the future of Islam in a global world.

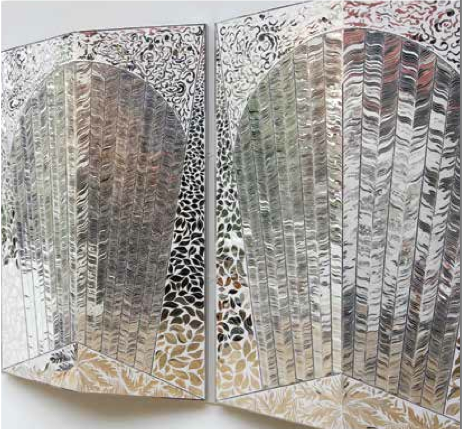

Monir Farmanfarmaian, Birds of Paradise, 2008

The most poignant piece in the show is by Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, who is 88 years old and lives in Iran. As a young woman, she left to study art in America, where she was friends and contemporaries with Andy Warhol and many Abstract Expressionist painters including Frank Stella, Jackson Pollock and Barnett Newman.

Birds of Paradise (2008) consists of two large panels made with mirror mosaic, a traditional architectural technique found in Iranian mosques. Cut mirror pieces are set into plaster and arranged into intricate patterns. These delicately cut parts are too small to reflect whole images; they instead reflect light and color in an abstract way, breaking it down into small pieces. The patterns, inspired by feathers left by sparrows on the artist’s balcony in Tehran, combine a personally poetic detail with a style of decorative arts that looks regal and palatial.

There is a vast difference between Farmanfarmaian’s magical-looking, architecturally inspired sculpture and Khalid’s equally detailed shawl, yet each manages to pair the personal with the collective, a strong theme in this show. In these thoughtful, studied considerations of the collective versus the individual, the role of a person as individual is not automatically assumed. There is a strong sense of interconnectivity seen in how each brick connects to a whole, how each golden pin is part of a larger pattern, how each scrolled prayer is nestled within another. These characteristics shed a different light on Islamic faith, which is the second largest in the world and one of the fastest growing.

Unless we have a specialized background in history or Islamic studies, what most of us hear and know about Islamic culture is limited by stereotypes. The real, personalized experiences shown in the Jameel Prize offer points for reflection about Islam’s role in our global future, and how we can see into our cultural differences rather than be deflected by ignorance.

3 comments

As a Spaniard I am very familiar with Arabic culture from the times of Abd al-Rahman I to the present. I also lived in Iran and I am well acquainted with the amazing arts and crafts of this country. This show presents some very interesting aspects of how this artists use their traditional crafts to convey new meanings and offer a different view of this very misunderstood culture/religion.

Thanks for this review. I’d be interested in clarification re- the statement that Koraichi’s works” do not have any literal, translatable meaning.” Was it your impression that Koraichi has the knowledge of Arabic to write intelligibly in the language if he wanted to? If so, is the writing total gibberish, or is it gibberish like Finnegan’s Wake?

Hi Carolyn, I emailed Tim Stanley about your question and he replied that yes, Rachid “is capable of writing texts in Arabic that make sense.” Also, he corrected my misunderstanding about the text on the banners being nonsensical. Instead, he explained that “the writing on the banners is not gibberish at all, but the texts are not meant to be read as a page in a book would be read. Lots of them are

incomplete, for example. The textual excerpts are visual references to

the works of the mystics, but you are supposed to look at them, not read

them.” I don’t read Arabic and misunderstood his description during his gallery talk. Thanks for asking for this clarification.