Over the course of a career spanning 30 years, James Drake has worked on and off the wall in mediums as diverse as welded steel, video and photography, always relying on drawing as his artistic backbone.

While he has often expressed himself using forms and images associated with masculinity and the implicit violence of his bordertown upbringing in El Paso (engines, guns, hunting trophies, wild animals), Towards the Pandemonium of The Sun tacks in an opposite direction. The pungency of his current imagery, which is conveyed entirely by charcoal drawings, is the result of the cross-pollination of fluent observation, a hand comfortable with an Old Master drawing style, and inventive mélanges of personal memories and historical associations that suggest a restless, panoramic landscape in search of a narrative.

The exhibition alternates between massively scaled drawings, replete with social commentary, and smaller, often highly personal sketches and collages that seem more preoccupied with piecing together the fragmentary nature of existence. Drake loads City of Tells (Barca de Oro) with characters from the apex of historical painting, and then proceeds to demolish the sense of spatial and historical continuity that they evoke. One of the shipwrecked sailors from Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa floats on his back in the watery foreground. Behind him, a lost soul from Delacroix’s The Barque of Dante gnashes his teeth. Rising from the water, sandwiched between these two historical artifacts, a young boy (the artist) presents a gift to an older man (his grandfather). Surmounting them in the sky, an enormous inverted head after Michelangelo’s “Fury” drawing hangs suspended from the top of Drake’s 12-foot high paper sheet. Ripped gashes in the paper course from top to bottom; exposing the paper’s silvery canvas backing, they evoke the jumbled, incandescent atmospheres of memories or dreams.

War in Heaven, on the other hand, is crisp, graphic and aggressively naturalistic. Drake’s precise use of stencils keeps the distinctions between the paper’s white and his vivid tonalities as iconic and theatrical as the distinctions in City of Tells (Barca de Oro) are congested and indeterminate. Drake’s content here also projects a different cadence. A hawk and a scorpion are depicted fighting over the corpse of a small bird. Dramatically grounded in one corner of the composition, this bit of food creates a powerful pivot for the tableaux. While the main players tussle, the many bit players in the food chain — bugs, spiders, flies and mosquitoes — clamor for a piece of the action. Drake suggests that his symbolic naturalism, which paraphrases folk legends about a trickster scorpion using guile to destroy a much larger adversary, be seen as a statement against war in general. War in Heaven also reads as a concise analogy for the territorial chaos of our current Iraq farrago.

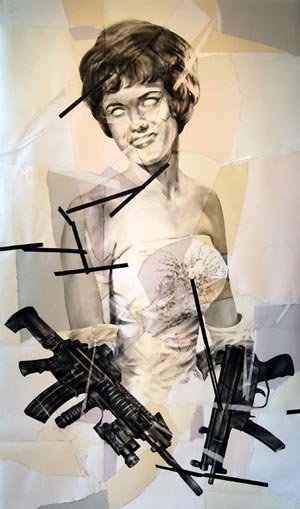

James Drake... Lock and Load the Golden Apple... 2005...Charcoal, tape, gold leaf on paper mounted on canvas... 120 x 72 inches...

Smaller in scale and more personal in nature, the suite of 13 drawings bearing the exhibition’s title channels the sardonic worldview of Goya using an expressive description reminiscent of Da Vinci, Carracci and Michelangelo. Working in a loose, sketchy manner, Drake clearly knows how to have fun with a piece of charcoal. Countering the suite’s voluptuousness is a fatalistic viewpoint every bit as acerbic as (if less frontal than) Leon Golub’s paintings of mercenaries. Each sheet is composed of one or more ripped pieces of paper that have been drawn on before their isolation within a larger sheet. This process highlights the extremis displayed by the character studies that fill these pages. While the man wearing glasses who looks up from the bottom of Between the Hammer and the Wood may or may not be an oblique self-portrait, this work certainly projects the intimate atmosphere of life experience. Drake describes his suite as “one of the most personal statements I have made to date, but loaded with social commentary because of the state of the world today.” Like characters from a novel by Drake’s friend Cormac McCarthy, the grotesques that populate Towards the Pandemonium of the Sun seem contaminated by life. Drake concentrates on nakedness, bookending his suite with an obese man seen in profile in Crossing Acheron and a similar figure viewed from the rear in Wading in Self-Pity . A naked man writhes in To and Fro; a scrawny bird exposes itself in The Naked Chicken . In Little Trumpet Fingers and The Lizard’s Vanity, the purity of the paper itself is eroded, splattered, ripped or otherwise degraded.

Drake’s approach has always ranged between the descriptive and narrative, and laconic, even minimal observations. But while he has flirted with abstraction, he has always come down on the side of the figurative. His newest work is catalyzed by an explosive combination of lyric naturalism and caustic, even mordant, wit. As in the work of William Kentridge, another contemporary artist long given to charcoal soliloquies, personal confessions and social critiques lurk throughout these assembled images. This is not the epic lineage presented in his monolithic drawing City of Tells, which was shown at Moody Gallery in 2004. There is a savagery to this new work that is expressed through a procession of torn, abraded, ripped and retaped, or otherwise intentionally fragmented pieces of paper; it is as if the artist, working in a fury or a rage, were intent on destruction as much as on creation. Or as if he has tried, in Drake’s words, “to incorporate destruction and healing in the same drawing.”

Images courtesy Moody Gallery.

Christopher French is an artist and writer currently living in Houston. He is also a contributing editor of Glasstire.