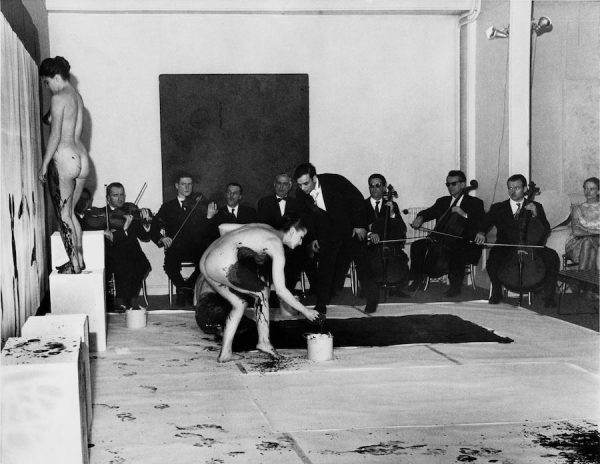

Yves Klein, Anthropometries of the blue period (1960)

Please go here to read Liss LaFleur and Colette Copeland’s recent conversation about the current exhibition ‘Cosmic to Corporeal: Contemporary Queer Performance Practices’, which LaFleur curated.

First, the myths:

- Performance Art is an excuse to get naked and roll around in paint.

- Performance Art is a poor substitute for REAL art.

- Performance artists are lazy, untalented artists who couldn’t cut it in painting or sculpture.

- Performance Art is boring, and should take a cue from a reality TV show like Botched, S*X Sent Me To The ER, or Dual Survivor.

- Performance Art tactics of self-mutilation and harm, crying, screaming, or yelling are selfish gestures used only for the purpose of making the audience as squeamish as possible.

- Marina Abramović is the only famous performance artist.

- Performance Art has to have an audience to count.

- It’s not Performance Art if you use technology.

- Performance Art is a way to torture/embarrass your parents.

- If you know when to applaud, you’re doing it wrong.

Debunking the Myths:

Colette Copeland: (1) Yves Klein may be singularly responsible for perpetuating this myth with his Anthropometry works, where he used women as human paint brushes, directing them to roll around on canvas and paper while covered in his signature Klein blue paint.

Janine Antoni, Loving Care, 1993

But using the body as a tool or medium to create work is about artists having agency and control over their bodies. Janine Antoni’s 1993 Loving Care performance (and more recently Kendall Jenner’s humorous video in W Magazine) challenges the notion of a woman’s body as object.

CC: (2) I can hear my students’ voices in my head, loud and clear, on this myth. When speaking about the American performance movement of 1960s, I remind my students that context is key to understanding the artists’ intentions. Artists were protesting the Vietnam War. The Civil Rights and Women’s Rights Movements were underway. Performance artists were challenging an art establishment that primarily exhibited and recognized white male artists who made painting and sculpture. Performance directly defied the traditions of what constitutes “art.” Performance art impacted social practice and created a foundation and legacy for artists working today.

CC: (3) See #2. Performance artists are innovators in using the body as a medium. Many start out in more traditional media such as painting or drawing, but evolve into performance as a strategy for addressing salient issues in a more direct and personal way.

ORLAN

CC: (4) The purpose of performance art (unlike reality TV) is not to entertain. Some works are meant to provoke the viewers as well as the artist in terms of testing the limits and endurance of the body. For example: in the 1990s the French artist ORLAN underwent multiple plastic surgeries to confront beauty standards, and this work predates reality TV shows like The Swan (2004) and Botched (2014-2017) by one to two decades.

Liss LaFleur: (5) In performance art, the body is the sculptural mass. Artists are continually exploring both the internal and external — and the virtual and physical — and limitations of what that means. Contemporary artists like Cassils, Ron Athey, and Doreen Garner create provocative work that trains and challenges the body and our expectations around identity, sexuality, and trauma. These gestures should not be seen as selfish, but reflective of larger shared experiences.

LL: (6) Often, when I mention performance art to anyone, in or outside of the art world, this is the first person they mention to me. Marina Abramović, known for her semi-recent MOMA retrospective and durational artwork The Artist is Present, is undeniably a force within performance art practices. However: she should by no means be the singular representation of performance art as a medium. A purist in many ways, her work extends into endurance art, feminist art, and the gaze, and continues to inspire a new generation of artists.

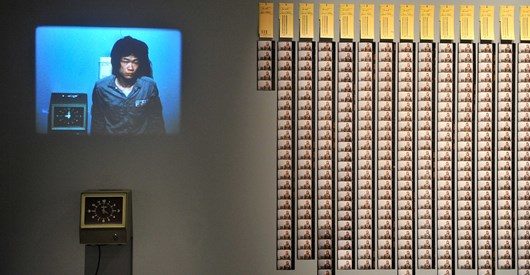

Tehching Hsieh, Time Clock Piece (One Year Performance 1980–1981) 1980–1981

CC: (7) For some performance artists, the audience is a key component for activating the work, and for others, performance is a solitary act. Tehching Hsieh’s one-year-long performances examined issues of work, time, struggle and confinement. In his Time Clock Piece (One Year Performance 1980–1981), he punched a time clock hourly for a year, documenting each punch with a photograph. This was performed as a solitary act of defiance without an audience present. The resulting documentation has been shown in gallery and museum exhibitions.

LL: (8) One major myth related to performance art is that it is not performance art if the artist uses technology to enhance, engage, or interpret their actions. This insinuates that amplification or technology cheapens or “fakes” the audience in some way — and that the work should not be deemed durational or performative. Speaking broadly, beyond just technology used to document a live event or happening, artists often engage in live audio/visual interactions, or perform directly (and solely) for the lens of the camera, and envision speculative spaces where bodies can live and perform. Signe Pierce, Pipilotti Rist, and Ragnar Kjartansson are three contemporary examples. One of my favorite artists merging physical and virtual performance practices is Jacolby Satterwhite. Check out his recent work Room for Living at the Fabric Workshop for more.

Patty Chang’s In Love (2001)

CC: (9) This myth makes me think of Patty Chang’s videos, especially In Love (2001), where she eats an onion in an intimate, kissing embrace with her parents; they pass the onion back and forth as tears stream down their faces. It had to be an uncomfortable experience for all involved, but it evokes a tender moment that speaks to her parents’ support of her work, while exploring the boundaries around love and family.

Nina Jan Beier and Marie Jan Lund

Clap in Time (All the People at Tate Modern) 2007

Performed as part of UBS Openings: Saturday Live – Actions and Interruptions, Tate Modern, 10 March 2007

Photo © Tate

LL: (10) This myth is tied to ideas of performance art as entertainment, and the idea of applause following the conclusion of a theatrical, operatic, or musical performance with a definitive beginning, middle and end. Performance art often times removes the “fourth wall,” making room for spectators to feel a direct response — whether it be clapping, crying, or laughter. Furthermore, there are a number of performance artists who use prompts to encourage the audience to clap, hum, or meditate. One of my favorite works that responds directly to this myth is the work Clap in Time (All the People at Tate Modern) made in 2007 by Nina Jan Beier and Marie Lund. For this work, Beier and Lund initiated a simple, large-scale participatory performance in which they asked everyone at Tate Modern to clap their hands in time beginning and ending at a specific time.