In this conversation, Renata Cassiano Alvarez and I discuss how language forms the foundation of her artistic practice, shaping not only communication but her perception, identity, and material choices. Influenced by her Mexican and Italian heritage, her work explores themes of archaeology, abstraction, architecture, and materiality, often using forms like arches and circles to signify passage and cyclical time. Throughout the conversation, we explore the power of uncertainty in art-making and meaning-making. We discuss the possibility and potential of resisting the desire to over-explain the process while encouraging viewers to discover their own interpretations in relationship to the object, preferring for the work to remain “mysterious and important.”

Carris Adams (CA): I created a Venn diagram of three overlapping elements of your practice: architecture, community, and material. I understood language to be a part of the community, but very quickly, I realized that language is the foundation of your practice.

Renata Cassiano Alvarez (RCA): Yes, I think language is at the base of it all. There are several entry points and layers to work through ideas and questions about language. Ten years ago, while I was in grad school and living in Massachusetts, I started realizing how much English was percolating into a lot of aspects of my life. We have always spoken two languages at home growing up. My father is Italian, and my mother, Mexican. I learned English in school. My parents were very into languages, and after English school, they sent me to French school. I am grateful for that because it taught me the power of the word.

I started using English professionally here in the US, and I started understanding how much language really determines many aspects of our lives. It determines our outlooks. It determines how we perceive things. Language even affects our physicality. Here is an example: when I think of my sculptures, I think of them as females. Because in Spanish, it’s la escultura, a female word. That’s how my brain functions. And with English, it was such a different way of thinking.

CA: Do you remember a time when language, your practice, and physicality overlapped?

RCA: Yes. When I first came to the U.S., I started lifting more weights, so my body started changing. I started thinking about how I could translate this change with material. I was in grad school at the time, making work about abstraction, history, and archaeology, which are the things that I am interested in.

How could you change the language of a material without being overly narrative? I don’t want to give people a narrative. I don’t want people to be like, “This is where it starts, and this is where it ends.” To me, everything is circular, and it’s more visual, and it’s more abstract and more visceral.

It was then that I started working with glaze as a casting material. This came from an infatuation with casting a lot of concrete. Just like concrete, I started adding aggregate to the glaze just to see what happened. This is how this mode of working came to be. It’s not only trying to understand the language of material but also pushing back on the conventions of the discipline.

When you’re brought up in ceramics, there are a lot of rules to follow. I didn’t start in ceramics — I started as a painter. In painting, there are rules, but they feel more flexible. So I kept wondering: why can’t ceramics be more flexible, too?

People always have issues with things that break and get put back together, with pieces being too heavy, with varying thicknesses, or even the length of a form — these details matter to them. But I wanted to push back against that.

For me, my process is about embracing language as an agent of change. Pushing back against convention isn’t just about rejecting it — it’s about embracing those conventions and pushing them to their limits. My work is heavy. It’s broken, and I put it back together. I use glue and epoxy — all these materials that are usually seen as cheapening the work because it’s not whole. But the work is whole.

In fact, the cracks, the cuts — all of that — tell more of a story than something pristine ever could. Pristine work is technically impressive, and yes, it’s beautiful. But for me, the work itself has to speak. I don’t want to paint every character for you — I want the presence of the work, its physicality, to tell you what you need to know.

Renata Cassiano Alvarez standing with her work in “Cuarto Verde,” on view at Conduit Gallery. Photo courtesy of the artist

CA: In this diagram, I also drew arrows that describe the circulation of the overlapping elements of your practice. The idea being that your objects rotate their emphasis. Some emphasize architecture at one moment, while others highlight material. What is your relationship to spontaneity and chance? With this work with Okay.

RCA: We work hand in hand. When I was 17, I saw a documentary about Robert Rauschenberg. When he talked about the collaboration with materials, it was eye-opening. Like many art students entering school, I tried to “master” it. I saw him not only using paint in a way that I hadn’t seen before, I heard him talk about material. He saw material as a collaborator and not something that you dominate.

That opened up the world to me. Since then, I have kept that at the forefront. To me, the material is a collaborator. And even though we don’t communicate verbally, we communicate physically through touch and sight, but we also communicate in the final result because chance, happenstance, and intuition — that’s really how I work.

I have a general sense of what’s going to happen, but there has to be an element of surprise. That’s where the challenge is for me. Working with something I don’t fully understand—that’s where it’s at.

Whenever a piece isn’t flowing, when I don’t immediately know what to do, that’s when I dig in deeper. And those, to me, are the best pieces. I wouldn’t call it a struggle, exactly — it’s more like moving forward without knowing where you’re going, like feeling your way through in the dark. And those are the moments when I know: this is it. This is where the best results come from — because it’s completely new, even to me. There are times when I need a specific outcome, but most of the time, it’s about uncertainty. I don’t always know if something will work, what will happen in the kiln, or if a piece will break entirely and need to be rebuilt.

In Cuarto Verde, there are two pieces that were completely destroyed when I cut them from the mold. At first, I thought, “I don’t have time for this — I just need to get the work done.” But then I realized: I have the materials, the glue, the epoxy — I can put them back together. Maybe not as they were originally, but in a way that creates something even more interesting.

That’s how I arrived at these pieces — massive forms, heavy on top, precariously held up by delicate tubes that feel like they could collapse at any moment.

Renata Cassiano Alvarez, “Serpiente en Negro,” 2024, ceramics, gold, and epoxy, 14 x 4.5 x 4.5 inches. Photo: Kes Efstathiou + Forrest Frederick

CA: In Serpiente en Negro, a frozen drip or ooze is happening in the middle of the object that looks like it could snap at any moment. This creates a certain kind of tension in the work and makes me think about your process and failure. How do failure and risk factor into these works?

RCA: I mean, failure is a possibility, but it’s also an opportunity to let go and transform. I see these moments as clues to inform the next moment. My parents are archaeologists and therefore that part of my brain turns on. As the viewer, you start putting all of these clues together, you can understand exactly what happened and how this came about. And I like that. I like that it is a little game that, if you had heard me talk about it enough, you’ll understand.

CA: I often see the archaeological influence in the work. These objects span time to me. They look like objects that have been newly unearthed, fragmented, and polished for our viewing. Sometimes, they look like miniature monoliths, portals, cathedrals, duomos — not to mention how you utilize color to point to your multicultural upbringing. These formal decisions are also their own language with each object having its own language. How or when do you decide to utilize arches, gold, or circular elements?

RCA: I am the product of these two things: Mexico and Italy, both places with a long history. I believe in the power of spaces. In my work, you could say that the arches come from Italy, and the circles come from Mexico. The circle is a very common symbol in pre-Hispanic cultures. And this circle signifies the time that never ends. It’s all cyclical. Everything comes back. I like to use those two symbols often — the arch as a gateway, as a passage through, and the circle as the signifier that everything comes back. So we keep going in circles into these passages constantly.

Funny enough, in grad school, I was told that my work ‘didn’t look Mexican enough.’ What does that mean? It means that they wanted a certain kind of performance from the work when, really, I was more interested in the things that I’m making now, and eventually, they got the point. Later on, when I was teaching, I tried to encourage my students to make work about what interests them, not about what others tell them. My intention was for the students to feel comfortable to make whatever they wanted.

Renata Cassiano Alvarez, “Minute Memory,” 2024, ceramics, 4 x 5 x 5 inches. Photo: Kes Efstathiou + Forrest Frederick

CA: Same same. I wanted to encourage students to develop a never-ending question that they wanted to answer through their medium. What question are you leading with right now?

RCA: The question of what something means — it’s always there. Right now, I find myself gravitating toward the knife. I don’t know exactly what it means to me yet, but I keep circling around it. I see the creative process visually, almost like a spiral, with the question at the center. When you start working with an idea, you’re at the outer edge, moving closer and closer until you reach the center — until you finally understand.

There’s a brief moment when you can hold both things at once: you’re still asking the question, but you almost know the answer. That window closes quickly, though. The more you talk about it, the more you understand, until suddenly — aha! — it’s clear.

Right now, beyond the question of what the knife means, I’m thinking about how to create objects that speak of time itself — the way an archaeological artifact does. I think that the beauty of being an artist is to be able to flow in between these things — to flow in the margins.

I’m also thinking about reflection and what it means to polish the surface to be so reflective that the viewer sees themself in the work and along the surface. You see yourself or a shadow of yourself in many ways.

Renata Cassiano Alvarez, “Mirar el Río hecho de Tiempo,” 2024, ceramics and gold leaf, 15 x 4 x 4 inches. Photo: Kes Efstathiou + Forrest Frederick

CA: There is a lot of romance in the idea of finding the hidden meaning, or finding the artifact. I think we all grew up on movies about an archaeological dig where someone discovers a dinosaur bone and begins brushing away dirt to reveal its true shape. Your objects have shapes that are emerging and abstract, and it’s the viewer who is doing the “digging” sometimes. You also created tiled platforms, tables, and shelves that not only connect to Mexican tile work, but also place the work on display as if recently discovered. Has there ever been an instance where the work emphasizes this discovery and is more hidden than revealed to us?

RCA: That’s how the work started! That was the original idea when these sculptures were much bigger. In the beginning, they were blocks and things were more hidden. They were little monoliths that contained things that you couldn’t see. But the logistics of being an artist got in the way such as storage, workspace, and the weight of lifting them. But don’t get me wrong, like our many cycles, monoliths will come back for me when the time is right.

CA: So this brings up the process and how these things are made. They have a mystery which I feel is hard to achieve in the artworld these days. We want to know too much, too fast, all the damn time. But I’d rather not discuss your process any more than it already exists in the world. Is it important to you that the viewer understands the process and labor?

RCA: Have you ever seen that Severance meme? It recently came out of that scene in Severance where one of the characters is explaining the work, and he says, “The work is mysterious and important.” I see the work as mysterious and important, and I don’t need the viewer to know how it’s made but to experience it as it exists in front of you, in this moment. And I understand it because we are living with such uncertainty, especially right now, that it’s hard to handle another uncertain thing. But uncertainty is always part of our lives, and so to embrace it is important to me — to embrace that uncertainty, not only in the process but in the understanding of the work for myself, too. I don’t want the work to have all the answers for me. I want the viewer and the object to collaborate and develop their own answers and language.

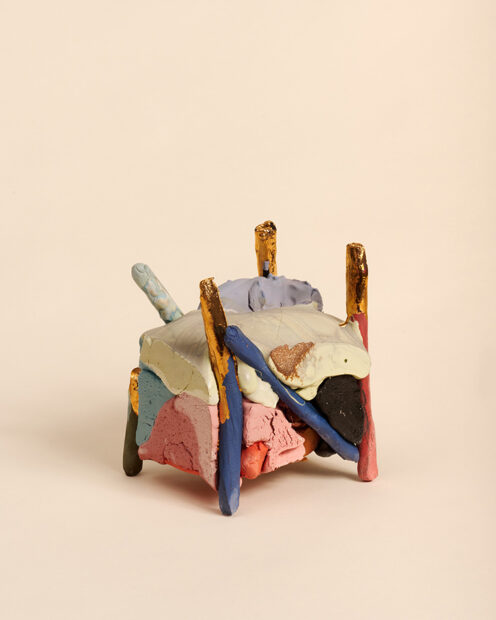

Renata Cassiano Alvarez, “Alvorada,” 2024, ceramics and gold, 8 x 8 x 8 inches. Photo: Kes Efstathiou + Forrest Frederick

Cuarto Verde is on view in Dallas at Conduit Gallery through April 19.