While the British artist Tacita Dean is much better known for her films, the exhibition of her work currently on view at the Menil Collection is comprised almost entirely of drawings. Given that this is the first major exhibition of her work in the U.S., it would be reasonable to ask why the decision was made to focus on the drawings. This question is easily answered by Dean herself, who claims that “[D]rawing is the thread that connects everything” (1). The show, titled Blind Folly, includes a selection of drawings dating from 1991 to 2024, and the way in which these works are connected, not only to each other but to the films (four of which are being screened sequentially), provides a clue as to how we might understand the work they might be said to be doing.

Because of — not despite — the show’s focus on drawing, I want to start with an observation Dean made about FILM, her 2011 film installation in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern. She begins by quoting the late filmmaker Harun Farocki on the difficulties he encountered when he first started editing digitally. “[T]here was,” Farocki said, “hardly any material resistance against the ideas”(2). Glossing Farocki’s comment, Dean reflects on her own process of editing analog film, writing, “The time it takes to implement an idea: to cut something in or take something out and then spool backwards to the beginning to watch how it has worked, is the time of film and the time of film edited, as well as the time of deep thought, concentration, and consideration. I need that material resistance to my ideas” (3). Dean needs this material resistance in her drawings as well (4). Moreover, this resistance extends to the support of each drawing, which is not “neutral” but is as integral to the work as its medium; indeed, the medium of these works could be said to include the support, which is often some kind of found material. This material interdependence can be found in the relationship between the chalk and the support in blackboard drawings like The Wreck of Hope (2022); in the preexisting incident in the drawings that utilize found painted slate like Blind Folly (2024) and Blind and Dusty (2024); and in Dean’s engagement with the postcard images in the Found Postcard Compliment (2019) drawings.

Dean’s preoccupation with material resistance is equaled by her preoccupation with time (as is evident from her comment above), which, paradoxically, is as relevant to her drawings as it is to her films. This is illustrated most explicitly in a 1998 drawing, Magnetic (Aviary): Crows, Raptors, Fowl, Game, Water Birds, Ornamental, Vulture, Garden, Seabirds (1996). In this Magnetic series work, Dean recorded the calls of various birds on magnetic tape. She then framed all the lengths of tape in each category — crows, raptors, fowl, etc. — noting the name of each bird on the corresponding length of tape. With the length of the tape corresponding to the duration of the call, Dean renders the temporal spatial (and visual). Another way in which Dean has incorporated temporality into her drawings is through the use of writing. For instance, many of the blackboard drawings include notations, and some of these notations have to do with time or reference dates (more on which below).

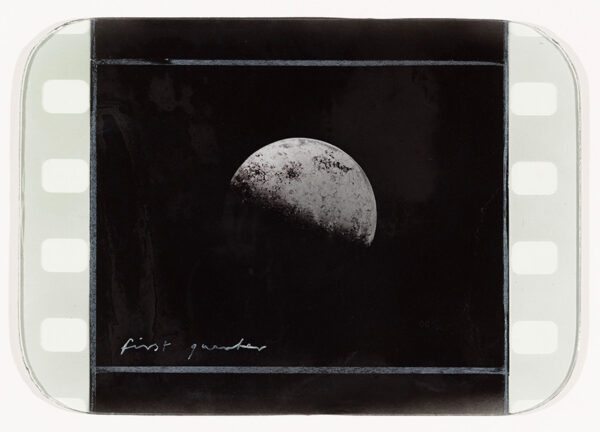

Tacita Dean, “The Sublunaries: First Quarter,” 2024, enamel and mirror lacquer on found

steam train windows, 12 1/8 × 17 3/16 × 3/16 inches. Courtesy of the artist; Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris/Los Angeles; and Frith Street Gallery, London. © Tacita Dean. Photo:

Studio Tacita Dean/Simon Hanzer

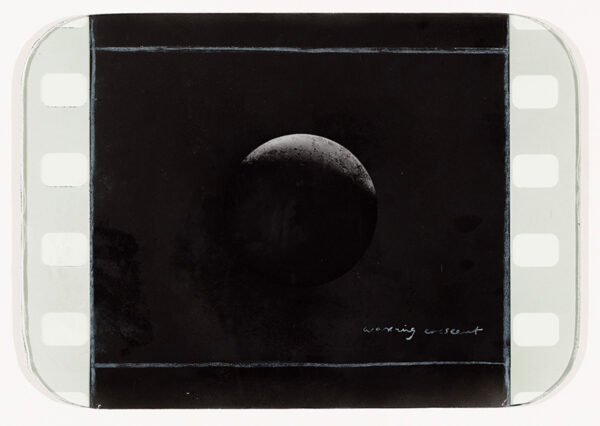

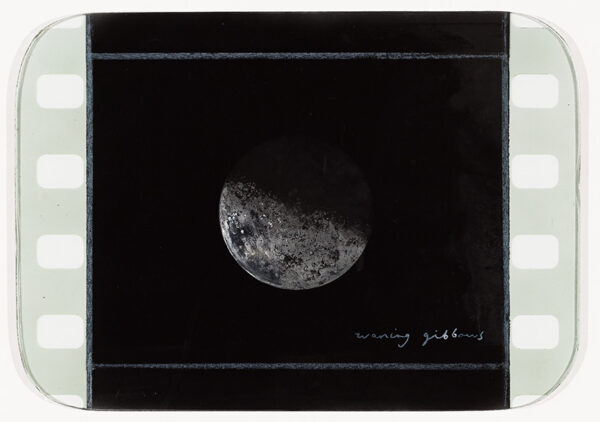

Some of the newest works in Dean’s oeuvre include the drawings she has recently made using found steam train windows. In the exhibition, these drawings line two perpendicular walls of one gallery, the walls forming an “L” shape. Each of the windows is lined on the bottom and top edges with translucent sprocket-like “holes,” making the two series of windows look like segments of film strips. On the short end of the “L” are eight drawings of the phases of the moon on black grounds, starting with an all but invisible (because it’s rendered in black) new moon. Like the new moon, each of the successive phases is labeled in white script underneath: waxing crescent, first quarter, waxing gibbous, full, waning gibbous, last quarter, waning crescent. Moving from one drawing to the next, the viewer effectively moves through both real space/time and cosmic space/time since movement through the gallery in real time is connected to the virtual time of film and, therefore, to the moon’s progression from one phase to the next.

On the long end of the “L” are four groups of drawings, each loosely connected by a particular focus or scheme. The first group pairs two images, one titled Fixed Foot and the other One Foot on Super 8. The second group picks up the foot reference, and the third and fourth introduce images of mountains, a tree, lightning, and the “hand of god.” The final image is of an eclipse. So, we proceed from the blindness of the not-quite-discernible new moon to the blindness of the eclipse: as Michelle White, the curator of the exhibition, notes in the book that accompanies the exhibition, “[F]or Dean, an eclipse represents the ultimate blindness, ‘the blindness of nature’” (5). In her essay, White focuses on blindness, which is central to Dean’s process, and references to it can be found throughout the show (6). As White explains, Dean’s reliance on blindness has to do with her lack of premeditation and interest in coincidences and chance encounters; it’s also related to the limitations of her mediums (7).

Tacita Dean, “The Sublunaries: Waxing Crescent,” 2024, enamel and mirror lacquer on found steam train windows, 12 1/8 × 17 3/16 × 3/16 inches. Courtesy of the artist; Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris/Los Angeles; and Frith Street Gallery, London. © Tacita Dean. Photo: Studio Tacita Dean/Simon Hanzer

In the steam train windows, Dean provides a corollary to the blindness of the new moon and the eclipse in her parenthetical references (in the titles of two works) to the “hypnagogic” and the “hypnopompic” — the transitional states of consciousness that are experienced while falling asleep and while waking up. Hallucinations associated with these states are brief, often vivid perceptual illusions. Dean has frequently spoken about the artist’s ability to work just below consciousness or below the “deliberate mind” (she has emphasized the importance of this in her writings on Cy Twombly), and, while they are fleeting visual images, hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations might be the closest we, as viewers, will ever get to this artist’s process (8).

Fixed Foot, the first steam train drawing on the long end of the “L,” depicts a mirrored image of a compass superimposed by a red grid (9). Here, the foot referred to is the anchored “foot” of the compass, a tool that delineates space or a space (a circle), its stasis reinforced by the grid. The foot is set in motion, at least virtually, in the next “frame,” titled One Foot on Super 8, which is a drawing of a human foot standing on a mirrored strip of Super 8 film (10). The four frames that make up the next set of images depict feet of various kinds — human feet, the cloven foot of the god Pan, the feet and ankles of an ancient sculpture of a charioteer that Dean is enamored of — standing on different gauges of film: Super 8, 16mm, 35mm, and 70mm. Placed as though they are standing on the film, the feet are “mobilized” as they walk along — or are seen to be conveyed by — the film. As a result of the mirroring of the figures in these images, the film strips in particular, these drawings include the reflection of the viewer, which has the effect of implicating us. I would argue that this strategy implies that we are responsible for the stewardship of this technology, that is analog film.

Tacita Dean, “The Sublunaries: Waning Gibbous,” 2024, enamel and mirror lacquer on found steam train windows, 12 1/8 × 17 3/16 × 3/16 inches. Courtesy of the artist; Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris/Los Angeles; and Frith Street Gallery, London. © Tacita Dean. Photo: Studio Tacita Dean/Simon Hanzer

This is not a Luddite’s nostalgic desire for a prelapsarian past; it is not a desire to go backward. Rather, the mirrored surfaces situate us firmly not only in the “here” but also in the “now”: the present is the only time apprehended by the mirror. Although Dean’s focus on obsolescence and loss and anachronism has contributed to the reputation she has garnered as an artist who is preoccupied with the past, she would beg to differ. “For me,” she said in an interview, “my work is always about the present” (11). Like many of the other drawings in the show, the locomotive drawings both assume and appeal to an embodied viewer, whose presence in the gallery is, of course, both “here” and “now.” Or as Maurice Merleau-Ponty put it, “Just as it is necessarily ‘here,’ the body necessarily exists ‘now’; it can never become ‘past.’” Dean’s crusade — I think it can be called that — to preserve analog film is not about the past; it’s about the future. It’s about the loss that would be sustained if celluloid were allowed to be superseded entirely by digital film. “[T]he point of this book,” Dean writes in the publication that accompanied FILM, is “to understand and preserve [film] as the independent and irreplaceable medium it is, and has been, and to make clear the incalculable loss to our cultural and social world if we let it… just disappear” (13). Of course, the choices we make in the present will determine whether analog film has a future.

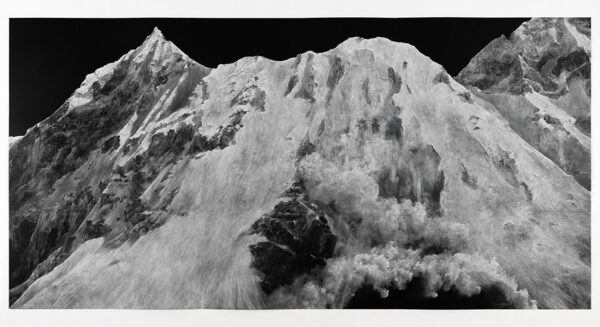

The phenomenological nature of the experience of the steam train drawings is reinforced in three large-scaled blackboard drawings titled The Wreck of Hope (2022), The Montafon Letter (2017) — both 24 feet across — and Sunset (2015), which is a little smaller (14). They are landscape images engaged with the sublime: The Wreck of Hope depicts a huge iceberg; The Montafon Letter, an avalanche; and Sunset, an immense cloud that seems to be glowing from within. Because Dean refuses to apply any fixative to the chalk, the insubstantiality of the drawings is evident not in spite of their monumental scale but because of it. And their material fragility is echoed in the ephemeral quality of the images’ subject matter.

Tacita Dean, “The Wreck of Hope,” 2022, chalk on blackboard, 144 1/8 × 288 3/16 inches. Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris/Los Angeles. Image courtesy of the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris/Los Angeles. © Tacita Dean. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio

There are stories behind these images — The Wreck of Hope alludes to a Caspar David Friedrich painting of a shipwreck, The Montafon Letter is related to some 17th-century correspondence about an avalanche, and Sunset references a giant cloud that Dean saw while she was driving down Sunset Boulevard — but it’s the monolithic nature of the objects they depict that we respond to. Initially, the drawings push us back toward the center of the room in order to view the totality of their broad expanses, but they also include tiny, human-scaled script, prompting us to draw closer to their surfaces in an effort to read the messages left us by the artist. The words and phrases, some of which are decipherable and some of which are not, do a couple of things. First, they introduce a textual (and temporal) element into a typically visual medium. And second, they amount to commentary, not on the work per se but on the artist’s process.

The timelessness typically ascribed to the artwork is undermined both by the chalk’s lack of fixative and by these “notes,” which, not coincidentally, often relate to time. In The Wreck of Hope, for instance, there is a note that says, “Sidney Felsen is 98 tomorrow.” There’s no knowing when that “tomorrow” was, only that it’s now in the past (although the present tense of the verb links that past to this present). There are also dates, “Sept. 3,” “12 August,” “2 Sept.,” and at the top, above the iceberg, the title of the work and the year “2022” (15). There are many other notations, many of them either rubbed out or illegible.

In some cases, their illegibility is the result of our inability to make out what the letters spell; it can also relate to the fact that the note is written not on the (black) ground of the drawing but on its (white) figure, i.e. the iceberg. In the latter case, since the notes are written in the same chalk used to render the iceberg, there’s not enough contrast between the figure (here, the writing) and the ground to decipher them. That the drawn words appear on both the iceberg and the negative space that surrounds it calls attention to the interdependence of the drawing’s figure(s) and ground(s), and to the material resistance of both. It also calls attention to the relationship between drawing and writing. Whether the artist considers the words to be drawn or written is not clear, but writing is what we usually encounter on a blackboard. Yet this writing is also drawing — or appears in a drawing. The punctuality of these notes, their connection not only to the time when the work was made but to the time of making, is also crucial. Like the locomotive drawings, these artworks seem to want to transgress their timelessness in favor of a connection to both real time — that is, the present — and to the virtual time of the drawing.

Tacita Dean, “The Montafon Letter,” 2017, chalk on blackboard, 144 × 288 inches. Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland. Image courtesy of the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris/Los Angeles. © Tacita Dean. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

So, what’s at stake in this work? I would argue that the stakes, for Dean, have to do with resistance — material resistance, in fact. As I’ve noted, Dean’s insistence on preserving and continuing to make work with photochemical film is connected to the material resistance that’s also crucial to her drawings. And the drawings instantiate this resistance for the viewer. In other words, resistance is elicited from or posed as a question to the viewer in various ways — phenomenologically, formally, temporally, materially (or in terms of medium), structurally, conceptually. Most crucially, it’s posed as a question about the cost involved in relinquishing analog processes altogether.

Becoming digital subjects doesn’t, or doesn’t only, involve a change from one format or technology to another; it means we are recruited — interpellated — by the digital (16). In an interview, Zadie Smith refers to digital technology as a “behavior modification system” (17). It’s not just that social media posts instruct us on what to be interested in; in other words, it’s not just the content of the post that matters. It’s that the structure of these digital technologies structures the way we think about thought: “That an argument is this long, that there are two sides to every debate, that they must be in fierce contest with each other” (18). While Smith acknowledges that we are modified by all mediums (books, TV, radio, etc.), digital mediums have changed our thinking and our way of thinking about thinking in deleterious ways. Dean, too, is wary: “We need to tread carefully into our digital future,” she writes (19). Her issue is not with our reliance on the internet or digital technologies per se — I think she would agree that they have distinct advantages. Instead, her issue is with the “bodyless, human-less world” that they portend if we don’t “tread carefully” (20).

In a 2011 show at the Whitney Museum titled Pro Tools, Cory Arcangel included Real Talk, a piece in which he had the museum enhance its Wi-Fi in the galleries by using temporarily installed signal repeaters (21). Arcangel was thrilled about the idea that viewers pausing in the galleries to look at their phones would “get the best reception they’ve had all day long” (22). That the artist not only anticipated the distractibility of his audience but actively encouraged it signals a kind of acknowledgment of — and capitulation to — viewers’ capture by digital media.

Tacita Dean, “Sunset,” 2015, chalk on blackboard, 96 × 192 inches. Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland. Image courtesy of the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris/Los Angeles. © Tacita Dean. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

By contrast, what Dean asks of us is that we attend to her drawings and films and that we do so in a particular way. The strategies I’ve outlined above prompt us to pay attention not just to what the images represent but to what they make manifest — materially, formally, temporally — and, self-reflexively, to the ways in which we engage with them. In their Twelve Theses on Attention, The Friends of Attention write, “An attentional path is the trace left by a free mind. To submit to the attentional path of another, to retrace it, is a form of attention” (23). In my view, this has something to do with Dean’s project. The eclecticism of her drawings (and I’ve mentioned only a few examples) means that there are not only numerous “attentional paths” for the viewer to retrace but numerous kinds of “attentional path.” Retracing is a kind of drawing (one that Dean herself has employed), and more to the point, it’s an analog process. Submitting to this process is, of course, a choice — one that Dean doesn’t coerce us to make but invites us to choose just as she would like to continue to be able to choose to make analog rather than digital films in her practice.

Dean’s focus on material resistance in this work and on the temporality of artmaking and art-viewing is an attempt to slow things down, to coax us into paying attention to the (analog) processes of the artist, to the passage of time, and to the opportunities that are afforded by submitting to both. In The Friar’s Doodle (2009), one of the four films that are being screened in the exhibition, the camera ranges across the surface of a photocopy of a drawing given to Dean by a young friar in the 1970s. Ostensibly, there isn’t much to this 13-minute film: the camera (re)traces the lines that make up the drawing without ever pulling back so that the viewer can see it in its entirety. The effect produced by this “all-overness” is not sameness because of the differences in the mark-making, and yet, because nothing “happens” in the film — there’s no narrative arc much less any kind of denouement or resolution — it might be seen as boring or redundant.

Presumably, the reason for the film’s duration is that it took thirteen minutes for the camera to record every inch of the drawing. The film is “addressed” to the viewer, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say it is addressed to a viewer, since there is a single, somewhat formal armchair on offer in the screening room (the kind of chair that one imagines might be occupied by a friar). This sets up a one-on-one encounter with the drawing, just as a single individual supposedly produced it. Although we never get to see the whole drawing, with some patience — and perhaps a few viewings — we might gain a more or less comprehensive sense of it. But I don’t think this is entirely the point. The point is that in our submission to the film’s retracing of this drawing we have spent time attending to the work and to the analog process that brought it into being. And this small act of resistance against our complete surrender to the digital is perhaps all that’s required.

1) Tacita Dean et al., Analogue: Drawings 1991-2006, 1st ed (Göttingen: Steidl, 2006)

2, 3, 13, 19, 20) Tacita Dean, Tacita Dean: Writing and Filmography, Reprint edition (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2018)

4) “I am an artist and I need the physical resistance of the material I am working with… Sometimes I use chalk on a blackboard or paint on a photograph.” Dean, 274.

5, 7) Michelle White, Blind Folly or How Tacita Dean Draws (MACK BOOKS, 2024), 24.

6) In addition to being the title of the exhibition, the phrase “blind folly” is the title of one of Dean’s most recent drawings and is cited in the drawing T&I (2006).

8) For Dean’s writing on Twombly’s ability to “work beneath his conscious level,” see Dean, Tacita Dean, 84; 249–50.

9) Most of the titles of the drawings in this series, including Fixed Foot, are lines from John Donne’s 1611 or 1612 poem “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning.” The central metaphor of the poem compares the speaker and his lover to two legs of a compass, which are always joined together.

10) Dean is clearly playing on the words “foot” and “footage” in numerous ways in this work.

11) Rina Carvajal and Tacita Dean, “Film is a Medium of Time: A Conversation with Tacita Dean,” in Briony Fer et al. Tacita Dean: Film Works (Milano: Charta/Miami Art Central, 2008), 61.

12) Also, “I am not in space and time, nor do I conceive space and time; I belong to them, my body combines with them and includes them.” Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Colin Smith (London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., 1962), 140.

14) There is a fourth blackboard drawing, The Delfern Tondo (2024), but there are differences between this drawing and the other three: it’s smaller in scale and it lacks writing.

15) Underneath the date “August 12,” Dean includes the name “Salman Rushdie.” This is the date, in 2022, when Rushdie was violently attacked in Chautauqua, New York. Thanks to Karen Schiff for reminding me of this date.

16) See Louis Althusser, “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses,” in Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, trans. Ben Brewster (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1971), 173ff.

17, 18) Ezra Klein, “Opinion | Zadie Smith on Populists, Frauds and Flip Phones,” The New York Times, September 17, 2024

21) Pro Tools is a brand of audio-editing software.

22) Andrea Scott, “Futurism,” The New Yorker, May 30, 2011, 34.

23) The Friends of Attention, Twelve Theses on Attention, ed. D. Graham Burnett and Stevie Knauss (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2022), n.p. Emphasis in the original. From the website of the Friends of Attention: “The Friends of Attention are a loose, informal network of creative collaborators, colleagues, and actual friends who share an interest in “ATTENTION” — the puzzles and problems of the focused mind and the directed senses. We are committed to ATTENTION ACTIVISM.”

Blind Folly is on view through April 19 at The Menil Collection.