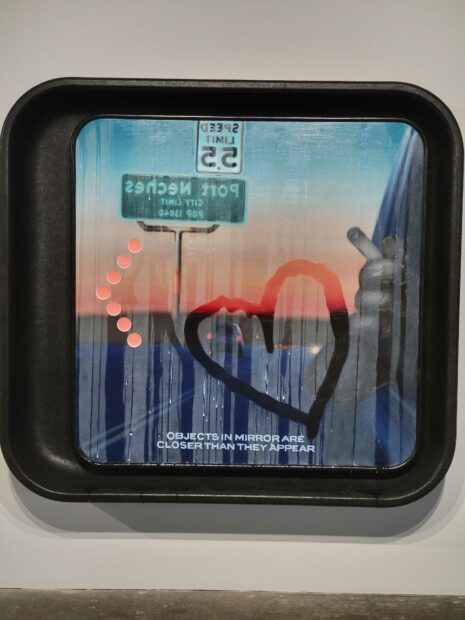

Chloe Chiasson, “Keep Left at the Fork,” 2023, acrylic, oil, LEDs, Plexiglass, resin on shaped panel, 72 1/4 x 78 x 12 inches

Hometowns have a complex allure. While many of us dreamt of escaping our hometowns, there is a long-storied pull back to the sites of youth. They truly are fraught places, filled with significant moments that inform our identities but also leave us grappling with labels that are imposed upon us. This rich duality — nostalgia and tension — is explored in Chloe Chiasson: Keep Left at the Fork at Dallas Contemporary, through a tour around a fictitious, small town in the south. I interviewed Chole Chiasson to dive deeper into the exhibition’s immersive narrative, which blends her own experiences growing up in Port Neches, Texas with imagined characters to forge new ways of viewing rural life through a queer lens.

Chloe Chiasson, “Crossroad Blues,” 2023, oil, acrylic, wood, foam, resin, Plexiglass, bolts, earring, canvas on shaped panel, 51 x 76 x 16 3/4 inches

Megan Wilson Krznarich (MWK): The exploration of Americana and small-town nostalgia is a theme you’re continuing in the works in this show. I would love to hear more about how your interest in this theme came about. How do you hope your works add a new layer to ideas of Americana?

Chloe Chiasson (CC): Growing up queer in a small southern town like those often revered in Americana, I wanted to present an honest, unflinching perspective of being queer within this distinct cultural context. At its core, Americana is this sort of need to preserve the look of the past, but the look of the past can be so different for those that never fit into the typical idealization of these places. In this way, working within this Americana genre and its associated imagery allows me to both celebrate and criticize these spaces; I’m using it as a vehicle to reshape the traditional domains of Americana and push viewers to expand the definition to include this multidimensional landscape — one that is unapologetically queer.

Chloe Chiasson, “A River Runs Through It,” 2021, oil, acrylic, resin, aluminum, fishing line, fishing hooks, wood, nails, cigarette butts, graphite, glass flakes, lipstick, hinge, ink on shaped canvas, 110 x 121 x 28 inches

MWK: The characters at the center of your works embody youth in different ways. In some ways, a hopeful tone, and in others a rebellious independence. I’d love to hear more about the role youth plays in your works and why you’ve focused on that stage of life for this exhibition.

CC: I think I fell into my focus on this coming-of-age narrative and youth as a sort of coping mechanism, or as a way to sift through this period of my life that I — like many other queer people — don’t feel as though I was able to fully experience. Certain applauded and harmless experiences would have instead come with repercussions for me, unlike other kids, like a first kiss or a first love. In many ways, I feel as though I missed out on the full youth or teenage experience. And, in many ways I feel as though I had one of the fullest.

It’s a really interesting contradiction for me, both a pensiveness for what could have been and a great appreciation for what was. Likewise, I have an interest in and appreciation for history and how it informs the present, and how this period of life is so important in our becoming. So, for the moment and for this exhibition, this period of life feels like the perfect muse to explore the what-ifs within a transformed, southern, queer space, to continue to lean into my memories of rebelling and growing, of learning what you can get away with, of seeking out spaces within these places.

That is paired with the always-present religious tone, that is to say: someone is always watching you. Is this good or bad? Perhaps one or the other, perhaps both, perhaps neither. There are times, periods of life, that spaces can be a home that offer comfort. And, there are times that that same space can become one that restricts and excludes. The present is constantly changing, made up of our emotions, thoughts, memories, and whatever we are seeing. The past, on the other hand, is fixed, tangible, concrete. So, figuring out how to work with and play with nostalgia, to play with the past, and open it up into something more present in a way that is universal and tangible, is a really interesting place for me. So, for now, I am enjoying reflecting on my upbringing, this sort of coming-of-age story, in a way that is reimagined and free.

Chloe Chiasson, “Highway to Hell,” 2022, mixed media installation with foam, wood, Plexiglass, acrylic, oil, felt, chain, wool, nylon, rubber, tablet with digital photo, height variable x 72 x 33 inches

MWK: I was caught by surprise by the mirrored nature of Highway to Hell, being thrust into the work unexpectedly. How do you want viewers to engage with the works? Are you wanting them to feel immersive? For visitors to feel part of the scenes?

CC: For me, a show is a time and a place where objects and images can perform together like characters and scenes in a film. For this show, I was thinking about the museum as a place embedded with memories of home, and I set about making pieces and arranging them so that it told a story and set a stage for the viewer to walk into, to become a part of. I want viewers to engage with the works in a way that feels immersive, that brings them into the scenes and into the world. Highway to Hell gives viewers permission to reflect upon themselves, to take the driver’s seat and perhaps be a judge of their own. For this particular work, but also the show in its entirety, I want to make the audience feel as though they are entering into the world of these characters, or perhaps interrupting, depending on who said audience is, which I think is interesting to think about and play on.

MWK: I love this idea. In addition to the mirrored element, the three-dimensional quality of these works, similarly to theater sets, enhances the feeling of the artworks entering the visitor’s space and visitors intruding upon the scenes. It’s a fun, engaging dynamic.

Chloe Chiasson, “Down on Saba Ln.,” 2023, oil, acrylic, aluminum, steel, foam, resin, bubble gum, canvas on shaped panel, 65 x 104 x 12 inches

I truly didn’t know exactly how to process my own encounter with these scenes. It forced me into the role of an outsider, in a way that I think fosters greater empathy for others that also feel outside of the standard narrative of the small-town ideal. At one moment, I felt myself seeking to relate, drawing upon my own experiences as a teenager. However, I am now a mother of teenage daughters and could feel a sense of being an unwanted authority figure, those ever-watching eyes ready to disrupt the moment. This is an election year and as noted in the show’s introductory panel, Texas is an epicenter for anti-LGBTQ+ legislation. Did this impact your feelings on exhibiting this work in Texas at this time?

CC: I wouldn’t say this impacted the work I made for the show, but I was pretty excited about the timing of when the show’s curator, Emily Edwards, offered this platform in my home state of Texas. I do not like to inundate my work with the political, nor do I like to respond directly to specific political events. But, I do see my work as engaged in politics, despite not using what you might call an overtly political language. It is there for those who can see it, and for those who can’t. Nonetheless, I very much enjoy the thought of my work taking up the space of a Texas museum during such a specific and important political moment.

Chloe Chiasson, “Red Rover, Red Rover,” 2022, oil, acrylic, wood, foam, resin, aluminum, nails, mason jar, cigarette butts, matches, coins, plastic, fishing wire, fishing hook, canvas on shaped panel, 71 1/2 x 266 x 14 1/2 inches

MWK: What do you hope visitors take away from this exhibition?

CC: I hope the show offers moments of reflection, memory, and relativity — that it brings people back to similar moments they may have experienced and how it shaped them. For queer people who maybe had similar struggles or are still having said struggles, I hope it is something of a comfort. Maybe a little “southern comfort.”

Chloe Chiasson: Keep Left at the Fork is on view at Dallas Contemporary through March 17, 2024.