Figurative oil painting, especially the allegorical kind, usually gets a bad rap as conservative and traditionalist — the pictorial language of official culture. That’s why I was pleasantly surprised to encounter four figurative oil painters in Pablo Cardoza Gallery’s latest exhibition, Circadian Visions, who reject these stereotypes with confident criticality. Yannina Taboada, John Duro, Sean Terrell, and Jenaro Goode challenge conventions with an avant-garde flair, often by utilizing confrontational pictorial tactics or perspectival acrobatics in their respective works.

In Yannina Taboada’s La Curiosidad (2023) a young, barefoot, brown-skinned girl calmly plays with two rattlesnakes in a desert landscape while a third can be seen making its way toward her from behind. The rhythmic tension of the painting — between the girl’s innocent smile and the danger intuited from the venomous animals — is made more alluring by the verdant green hills and placid blue lake in the background. With the lilac and gold of the girl’s dress and the ruby red sunset behind her, the painting vibrantly pulses with color. The iconography subtly alludes to Coatlicue, the Mesoamerican earth goddess and mother of creation and destruction who is typically represented with a serpent skirt, but it appears as though Taboada has rendered her as an ordinary and relatable young girl.

This type of realism occurs again in Taboada’s El Primer Nivel a Mictlán, la guia del Perro (2022), in which a young girl who sits barefoot in a courtyard hypnotically stares beyond the moonlit picture plane while three dogs guard her, one growling at the viewer. Here, Taboada’s title alludes to the first level of Mictlán, the Aztec underworld, but the painting represents it as part of this world, suggesting that this liminal zone between life and eternal rest could be a familiar place one might inhabit. Taboada’s delicious mixture of colors makes me want to come closer, but the snarling dog makes me hesitate. Paradoxically evoking a paralytic desire, Taboada’s paintings call to mind the words of the poet and scholar Gloria Anzaldúa, who described her own brush with death as a call to action: “…Why do I cast no shadow? / Are there lights from all sides shining on me? / Ahead, ahead. / curled up inside the serpent’s coils, / the damp breath of death on my face. / I knew at that instant: something must change / or I’d die. / Algo tenía que cambiar.”(1). One of Taboada’s strengths is her ability to depict themes of social significance on an approachably human scale.

John Duro also seems interested in belief systems and social constructs, but especially ones that bring to consciousness moments of dysfunction or exclusion. Duro’s Downtown Overdose (2024) is hung so that a lone figure’s contorted face — an inscrutable mixture of agony and ecstasy — confronted me as soon as I entered the gallery. Although the figure sits awkwardly on a bench alongside a duffle bag and Narcan nasal spray, Duro has otherwise isolated this man, rendering him floating in an enveloping sea of black paint, like a twenty-first century typological specimen of misery. The overdose, which Duro has rendered sketchily, recalls Édouard Manet’s nineteenth-century portraits of social outcasts like The Ragpicker (c. 1865-1870), which Manet similarly situated in an abstracted monochromatic space. Although Duro’s painting is unsettling, the scale is small enough that the figure has a diminutive appearance which conceptually distanced me from the subject and elicited, predictably, condescending feelings of pity and shame. Perhaps, had the artist rendered the figure life-sized, I might have been led to negotiate his presence in a more complex way.

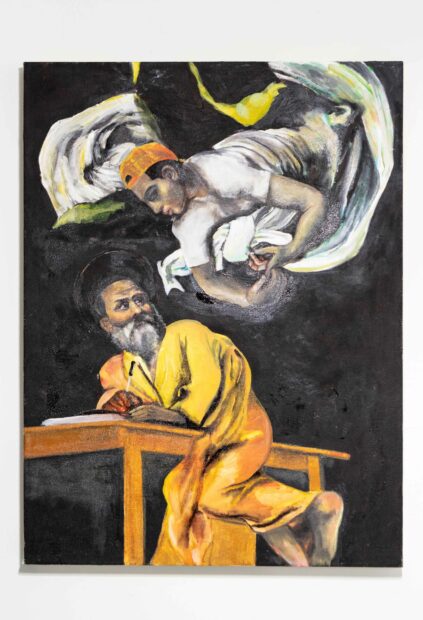

Another painting by Duro, The Inspiration of Zoe God (2023-24), reproduces Caravaggio’s The Inspiration of Saint Matthew (1602), but renders Matthew and the angel with a darker complexion and the angel with a white T-shirt and backward orange cap. Duro’s transformation of Caravaggio’s idealized figures into relatable modern ones recalls the history of Caravaggio’s own first attempt (rejected by his patrons Francesco Contarelli and the priests of S. Luigi) to render Matthew as an ordinary mortal, “inviting the viewer,” according to art historian Troy Thomas, “to identify with, sympathize with, and perhaps even be amused by Matthew rather than venerate him” (2). Duro’s transformative action not only tips the hat to the older artist’s original intention, but levels the field with a playful sense of irony.

John Duro, “The Inspiration of Zoe God,” 2023-24, oil on canvas, 40 x 30 inches. Photo: Emily Peacock.

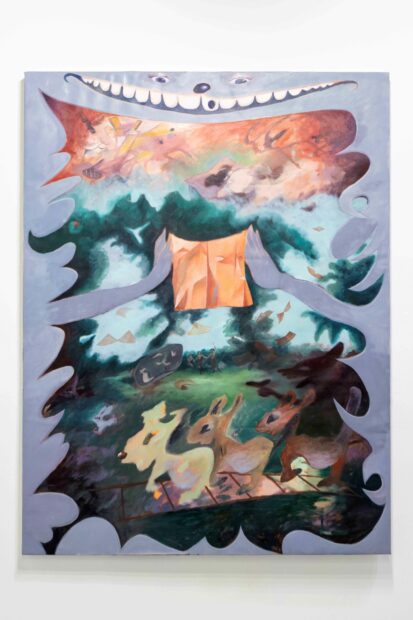

If Taboada and Duro show an interest in recreating familiar allegories in provocative new ways, then Sean Terrell’s allegorical inclinations in Viewing II, The Holder (2023) result in thought-provoking incoherence. Terrell’s lone contribution to the exhibition is comprised of a heady dreamscape where a Cheshire cat frames a hazy and complex tripartite scene replete with historical symbols whose meanings have all but evaporated into an ether of painterly abstraction. In the painting’s upper register, a cloudy cartoonish brawl with unidentifiable assailants takes place while documents and paper bills carelessly rain down throughout the second register like unnecessary legislation. In the second register, upon a grassy field, three figures in loincloths (one holds a spear) dance triumphantly while smoke seems to billow from the pale blue background. In the foreground, ominous and shadowy cartoon creatures hop along the squares of a game board while one shadow points and laughs menacingly. The cat who frames it all holds — with outstretched arms in the center of the painting — a flesh-toned cloth whose creases and colors are reminiscent of the bodies and drapery in Picasso’s African and Iberian-inspired brothel scene, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Terrell’s juxtaposition of historically dislodged motifs — from a floating rune to a three-eyed cartoon — had the effect of warping my sense of time, as if the painting’s representations exist in a pre- (or post-) historical dystopia. At a time when legislators in the U.S. are passing laws that redefine how history can be taught in schools and the culture wars of the 1990s seem to have returned with new disturbing mutations, Terrell’s painting reads like a bellwether of societal dysfunction to come.

Installation view of “Circadian Visions” at Pablo Cardoza Gallery, January 12-March 10, 2024. Photo: Emily Peacock.

The genre paintings by Jenaro Goode are less anxious than Terrell’s work, yet similarly disorienting. They take, as their subject, familiar scenes of everyday life, but ones made uncanny by way of the artist’s perspectival ingenuities. In Oak (dominoes) (2021), we do not so much look in on a scene of domino players than we are invited to be a domino player as we inhabit someone else’s body and perspective as a participant in the game. Before us, our hands hold seven dominoes in an anatomically implausible position as we contemplate our next move. With Goode’s skillful technique, the paint both glitters and glistens on the surface and provides his subjects with sculptural density, which creates a hallucinatory hinge between the painting as representation and the haptic materiality of the paint itself. In this way the domino players radiate presence and suggest Goode’s approach to picture making is a phenomenological one steeped in empathy.

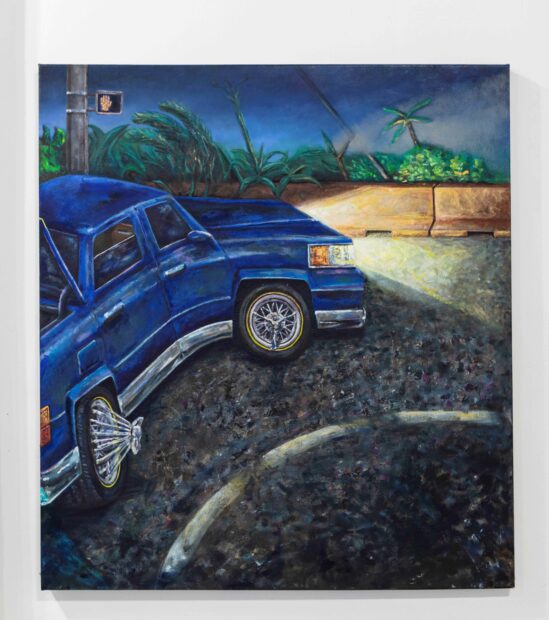

Take BLOCKBENDING (2022), for instance, Goode’s depiction of a tricked-out slab with elbows out that imaginatively bends down its middle as it turns a corner. Rather than rely on the classical idealism of Renaissance perspective, Goode seems more interested in working from an embodied perspective that makes visible the presence emanating from the car itself. While this perceptual trick of bending the car at first seems like a whimsical gesture, Goode’s attention to his subject conveys the more poetic intimation that this slab is bending in rhythmic harmony with the curve in the street upon which it glides, as if its sole purpose is to be, as the rapper E.S.G. might say, “sailin’ da south.”

These four painters approach social themes — some of religious significance — with personal perspectives that bring attention to what’s at stake in storytelling. Their drive to reconceive origin stories and question existing forms of representation conveys to me a desire to choose creative intervention over unconscious repetition. Time will tell whether the rest of us catch on.

Circadian Visions is on view at Pablo Cardoza Gallery in Houston through March 10, 2024.

1. Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute, 1987), 56-57.

2. Troy Thomas, “Expressive Aspects of Caravaggio’s First Inspiration of Saint Matthew,” The Art Bulletin 67, no. 4 (December 1985): 643.