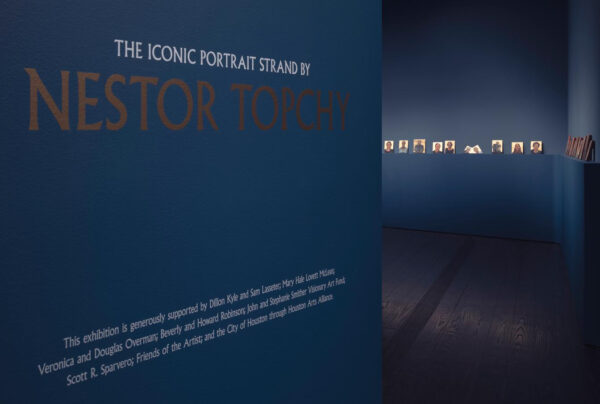

Installation view of “The Iconic Portrait Strand By Nestor Topchy.” Photo: Paul Hester/Menil Collection

I met Nestor Topchy about ten years ago, during meeting at a Thai restaurant that was meant to garner interest in his HIVE project, an artist community concept Topchy has championed over the years. My impression of him was that of wonder. I knew little of his art, but was strongly impressed by his persona — his intensity seemed to match the grand scope of his pitch. I doubt he remembers that brief meeting, but over the years, I did. I was thrilled to learn of his now-current and soon-to-close exhibition at the Menil. Seeing the work on display confirmed my admiration for Topchy. The following interview is meant to give a glimpse into this visionary’s mindset, concerning not only his art, but more significantly, his ideas around and passion for life.

Garland Fielder (GF): Concerning the portraits at the Menil, I was really impressed with the longevity of your idea. There seems to be a hard-won freedom there. I had heard about your portraits, but didn’t realize you had been working on them for so long, and then when I heard you explain that building personal relationships is sort of the king fish of your whole approach, I was really interested in that. It struck me that these are coming from someone mature in their understanding of how they relate to their art practice.

Nestor Topchy (NT): It’s kind of like the combination of these parts makes the totality over time.

GF: That leads to a sort of freedom?

NT: There is something about freedom, as it’s explained in different traditions… you’re not moved by these expectations, disappointments. You’re balanced and ready for these situations that come that would otherwise be disappointing. Some other situation could come that would be cause for great excitement. But to have this peace means not to be swayed… To have this peace regardless. That’s a really envious place to be, you know?

GF: It is. Whatever one’s chosen vocation, or if you’re a creator, when you can actually start to focus on letting go, I think the work infinitely improves. And you have to be completely committed so that no matter what you think of it, or you think other people think of it, you understand that this is today, and tomorrow is something different. What will remain is showing up on time and carrying through the process of the making.

NT: I think that you have to have skill and that takes time to develop, and that’s when you’re free. A lot of hootenanny can happen, and that’s okay. It’s a very different attitude when you have the skills to then ask, “Where shall I go? I can go here, and here, and here, and be informed.” I think a lot of artwork that is visual got literalized, got made into literature… for ideas, for systemic kind of uniformity.

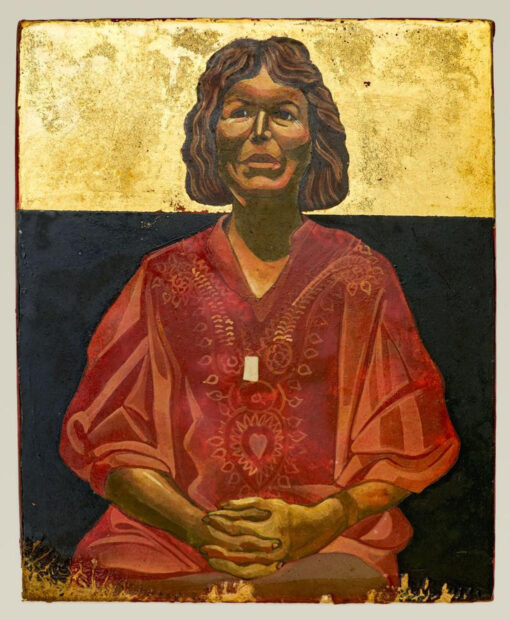

Nestor Topchy, “Iconic Portrait Strand (Terrell James), 2008-23, egg tempera and gold leaf on gesso over cloth on plywood. Courtesy of the artist, © Nestor Topchy. Photo: Caroline Philippone

So in the exhibition there is a portrait of Andrei Tarkovsky [the Russian director and screenwriter], and I have an egg on his shoulder. Now, I’m not so sure he would have liked that, but hey, he was dead by the time I wanted to do his portrait. And we had a friend in common. At the time I was asking sitters to include someone in the portrait who was a mentor, or someone who meant a lot to them… so there is a connectivity, and I could do a diptych. Some people were choosing to be with their partners in life, and others had somebody who meant something, and so I would include them. For instance, Derek Boshier chose Samual Beckett, and I was delighted to be able to, by extension, put Beckett into the portrait. I’m sure if I had met him I would have loved him, you know? And Edward Albee chose Elizabeth McBride, whom he referred to as “My Elizabeth.”

GF: These portraits bring you closer to another person, and also bring those people closer to each other; it’s a very inclusive thing to allow shared references to be part of the series. I assume every choice is a conscious one…

NT: I don’t do anything arbitrary, really. So there is a normal scale in the paintings that comes from the tradition of icon writing. Most of the work is small, because it’s made on boards, wood, and it’s heavy… it’s much more portable the smaller it is. But then if there is a really large portrait piece, it takes quite a resource — it takes a tree and you have to put the staves in and it’s heavy and it’s a major thing. And I wasn’t looking for that. So the work is naturally small.

GF: Of course, it lends itself to an intimacy. We’re talking about six inches by eight inches or so? I couldn’t help but feel my own presence when looking at the exhibition, at the little paintings leaning against the wall resting upon the surrounding shelf.

NT: Being a sculptor, that kinesthetic quality is something I always look for. It’s also a modern concept as well. The idea that the viewer is completely responsible for the content. So with minimalism, take Robert Ryman… how do you approach that? For someone who is not versed in that type of modernism, it can be a real challenge — they don’t know what to do. And to some degree that can be the point — you have to be comfortable in yourself and project or understand that there is something going on between you and the work, and to be open to what that is.

GF: I think that’s really difficult for people who aren’t artists to understand…

NT: …and yet, it’s possible to forget that what we are looking at here is painting. And that a painting, any kind of painting, has more in common with itself than it does with a living thing. We’re still looking at art. That’s probably the reason why forgeries done by that guy who created “Vermeers” back in the 1930s or 40s got busted. Nowadays we look at those paintings and we think “how could they make that mistake?” So we are, sort of, of our time.

GF: Because we’ve seen so many facsimiles of Vermeer’s paintings?

NT: Good luck fooling somebody now! Not only that, but we now have radio spectrometers, etc. We have all this stuff.

One thing that I sometimes talk about with the work is the uncanny valley. Because the work rhymes with that. Because we have a situation where proto renaissance painting, iconic works, by, say, Duccio, have this naturalism that is only slight, and then this quality that some people associate with type. I don’t think of it as type, I think of it as abstraction of sorts, or an ideal of some kind of noetic way that isn’t quite here — it’s aspiring towards something that we don’t understand, and then honoring that mystery.

I try to keep it simple as much as I can, because irony is really cheap, and it’s going to show up everywhere anyway, and you can’t control that, so don’t worry about that. Ken Wilber said, “A pox on irony!!” So, often what I do is submit to each portrait more and more, so as it develops, I’m sensitive and aware and open to where it wants to go. Some of them go haywire, and that’s okay, some of them don’t, and that’s okay. It’s like, well, I never promised anybody anything but authenticity and honesty in what I’m doing. So, in other words, the moments that may not have occurred to me, which if I’m aware of, I take advantage of…

Nestor Topchy, “Iconic Portrait Strand (Mary Ellen Carroll),” 2008-23, egg tempera and gold leaf on gesso over cloth on plywood. Courtesy of the artist, © Nestor Topchy. Photo: Caroline Philippone

GF: The little moments in the process? Or moments you discover with the sitter?

NT: I sketch really quickly, then I fix the drawing so it’s right. Then when I’m doing the painting things are occurring as they develop that have something that’s separate, some formal quality or balance or something I think will be…

GF: … discovered more than intended?

NT: Well, I mean, to say that I intend everything is to be disingenuous. I think that as part of what we do as artists is we have a system that we use, a set of protocols and materials and all that, and then once we become used to what happens when we work long enough, we are really outside of planning something for being surprised or anything like that at all. I don’t think there’s any thought in that. But there is creation that’s steered through… like, you can see where it’s going, and you go with that, and you let it slowly develop that way.

GF: And you have an internal trust system built up because you know exactly what you’re doing?

NT: Absolutely, completely trust it.

GF: Somehow, exactly knowing what you’re doing doesn’t wind up boring. It’s quite the opposite. It opens up a panoply.

NT: It’s almost like you know exactly, but you’re not quite certain. You know that things are going to have plenty of freedom and surprises. Or you make a decision unexpectedly… I love that.

It’s that sweet spot, and that spot rhymes with the Goldilocks equation. I mean, our planet has this thin onion skin, everything is exactly the right distance from the sun, the right chemicals and materials, the right everything, and all this stuff just happens.

GF: I love that connection. I heard this definition of humanity the other day that really affected me. I think it was Sagan, but it goes that “humans are the universe’s desire to observe itself.”

NT: That’s right…

GF: I never really heard it put that way. Somehow it put so much faith in me, when I heard that phrase, because the universe is so immensely vast and old and the numbers are so mind-boggling, but to somehow discover a purpose at the end of it, and that purpose is you…

NT: Think about what had to happen for you to get here.

GF: …in terms of stardust gathering and solidifying…

NT: Everything, every single thing, every bit of it. So yeah, the universe is expressing itself through this person at that moment, and another person at another moment.

GF: I’m usually pretty deflated after a solo opening. I feel, not depressed, but pretty flat… spent. Do you feel any of that with this show?

NT: No, I don’t. The real work is done on this plateau, always, and then there’s this peak experience which is the earned part. That boom, and you earned that plateau. And then there’s another plateau and that’s when a lot of work is getting done. Seen in that way, it’s easy to understand emotions this way or that way as not being entirely relevant to what is going on. That there are these parallels that are going on. And observing ourselves gives us distance to appreciate ourselves. And so that means that planning things is much easier, too. You could say these ideas, where are they coming from and where are they going and what are they about and should I be infatuated with this idea? Why? So it helps strategize a lot, it helps save a lot of time. It’s like there’s this big buffet table out and there are so many things that I can do, and I often overreach. I try to keep it reigned in.

Installation view of “The Iconic Portrait Strand By Nestor Topchy.” Photo: Paul Hester/Menil Collection

GF: Parameters can be good.

NT: Well, Buddhists starved and starved as an aesthetic and it was like, too harsh, and the other way was to be indulgent… they arrive at a middle approach, balance, everything-in-the-right-amount kind of idea… that sounds kind of namby-pamby, but it’s not. If what you’re doing is letting an idea drive a phenomenon, that can take it someplace absurd, and it’s no longer visual or a tactile art. And I’m speaking from the point of my goal, which is to make artwork. I want to make artwork that doesn’t sell you an idea; I want to make artwork that’s a phenomenon, that embodies a lot of what life is, that is profound in different ways, depending on how you looked at it. It would be a living… sort of like a station in how we imbue inanimate objects with our own animus… We bring them to life, we anthropomorphize things.

I’m not mechanistic, or a materialist, or a Dawkins fan, per se. I think there’s a sort of a priori arising of consciousness that came all the way through and all the way up naturally, that grew. Whereas what we’re doing is assembling when we come up with AI. The physicist Max Tegmark has been calling for a moratorium on the practice of AI. He’s looking at people just racing each other to get the coin, and it’s dangerous. There’s no guarantee that this so-called intelligence is going to care about us. He’s saying it’s like there’s a road crew and an ant hill: the crew isn’t out to kill the ant hill, but the hill is just in the way. So there’s a whole lot of things that can go wrong, even if it’s intelligent or not. This could be the biggest problem for humanity ever, at this moment. So it’s prudent, even if this is a remote possibility, why wouldn’t we say “hold on, slow down.” It’s in the best interest of our species to take a break here.

A lot of people kvetch about how things are now, but when you think about it, in terms of data, there’s never been as good a time to be alive for a person.

GF: Yes, there are lots of reasons to be hopeful.

NT: And I am thinking about myself and my justification of how the work comes from a tradition of icon writing in terms of its formal arrangement and materials and what not, which I think are profound. I’m still careful to say that the pieces come from a place of perspective, passion, and emotion. What comes from that expression through the icon… My paintings are not icons. For me, there are things in there that would disqualify them out and out as icons. I hope others can see that too.

GF: You prefer “iconic” or “iconographic”?

NT: Yeah. I don’t want them to think this is some kind of reimagination. I don’t think a lot of people would, but some might.

GF: Some of the work I’ve been making in the past years includes paintings, drawings, sculpture and installation. I think of them as relics from an unknown religion… physical attributes of a faith clouded in time, or memory or whatever…

NT: It triggers some otherness that maybe informs it, but is larger than that.

GF: It’s also reverent of that. It’s far away from irony. Like you, I’m weary of irony in my work.

NT: Well, it’s cheap. It’s easy. There are traps like that. Many artists are better off avoiding it… or not necessarily avoiding it, just flying over it…

That’s what exacerbates a certain modus operandi in politics, in the way that they lead or they create things, that of short-term use and a longer-term consequence. We are sort of wired to do that, to be super efficient. Our whole being is geared around that… When we see, our eyes only see a certain window, right in front of us that’s not blurry, and everything else is blurry, but we stitch it all together in our mind, because if our eye had to be the thing that did all that work, it would have to be much more designed and we’d have to have a brain that was huge and we’d need a lot more blood. We wouldn’t be like people at all.

Nestor Topchy, “Iconic Portrait Strand (Andrea Grover),” 2008-23, egg tempera and gold leaf on gesso over cloth on plywood. Courtesy of the artist, © Nestor Topchy. Photo: Caroline Philippone

GF: So the brain says, “filter”?

NT: The brain has to filter, or the breakers trip, right? The breakers trip and you become unconscious, because it can’t do that. It’s like pushing a race car downhill faster than it could ever go. So we have momentary lapses where certain states of mind, hallucinogens, whatever, can trigger a much more full realization through the senses than is normal in everyday experience… sort of kick the door open for a few minutes and then it’s like, wow, okay. I just got something or that just rewired me in a certain way. If you were like that all the time it would be very costly, you couldn’t maintain the status quo of function because your body can’t handle that.

Buddha held up a flower, sits down and boom! You have an epiphany, like a lightning bolt. So there is the ability for that kind of thing to happen… lever moments when something is switched.

GF: When my wife and I had our child, I had this distinct feeling that the cosmos had used me. I had fulfilled what I’m here for, DNA transference, right? But that’s just one level. I had no idea that it would be so transformational. You just can’t really compare it to anything.

NT: It’s a pivotal moment. Clear as day. Having a child made me change my practice, too. I looked around and I saw dead wood, and where I saw dead wood, it had to go. It was like, there was no question. There were things I stopped doing, there were people I stopped associating with. There were people that I picked up… all this stuff happened, and there was no longer this luxurious fooling around that we have as a right, sort of, in our twenties. I had a big space that went away; I had to work differently. It was necessary for (my wife) Mariana to get her sleep. So I had the morning shift, which meant teaching was an absurd thing to do because I would have to bring my daughter with me and put her in childcare at the school. I realized the amount of money you could make as an adjunct professor was not livable, at all. And that’s a tragedy in our educational system, amongst other tragedies. It needs to change.

GF: I couldn’t agree with you more.

NT: So, I would be there, present, working in my studio, being home with my daughter, and weekends we would go work on some Chinese painting. I found a Chinese scholar in Bellaire, and my daughter would come with me and do calligraphy and painting with me and we could do that until afternoon. Then we would come home and Mariana would get up (you know, she’s up till 4 in the morning keeping Avant Garden, her business, running). That way we could cover our bases, right? She made a lot more money than I could ever make as an adjunct professor, so what I decided to really do was concentrate on my art. And this gave me a way to have certain timeframes… and this also meant that the work I did had to be kind of sculptural and methodical, where I could work a few hours and quit and come back and work on it some more. It was not like the romantic ideal of an abstract expressionist smoking a cigarette and contemplating and losing the thread like Jackson Pollock and asking “Where am I now?” You know, being so self absorbed… I mean, that’s not the kind of parent you want to have.

GF: I’m not so sure that type of paradigm pays dividends for the artist either… But a lot of people think that’s what it means to be an artist.

NT: Right, that’s when you have the luxury of fooling around — nobody depending on you so much. There’s a certain kind of work that comes from that, but that wasn’t what I was going to be able to do or what I wanted to do. So I got to dig in and refocus and reconnect with familiar modes of working and familiar structures that were in my life in the beginning. I could see that there was a starting place where people already had respect, and I could expand upon that, so that was better to do in some ways than pretending that wasn’t there. You know, like calm abiding, where it’s like okay, this thing is presenting itself right in front of you, pick that fruit and don’t worry about it, because there are so many other things you can do and why not do one that’s going to be immediately conducive toward progress. A lot of people think since they’re great baseball players they can play basketball, or a great doctor can fly a Cessna, we know how that goes… it always crashes!

The Iconic Portrait Strand By Nestor Topchy is on view at the Menil Collection through January 21, 2024. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

2 comments

His show is transcendent. And this was fun to hear him talk about life and his process of creating. Thanks.

So wonderful to hear the serious spirit nature of art once again being discussed by you two respected gentlemen. The Houston Menil Legacy is back via critique and polite conversation. Wanting more. It’s phenomenal!