Stupid Painting with your lack of ideas

I won’t say “Conceptual Art.” It’s a lie, and not the good you-kinda-look-like-Idris-Elba lie, but more like the wretched no-such-thing-as-a-stupid-question kind of lie. To call one tradition “conceptual” is perhaps a diss to all others, implying they are void of intellect. Or maybe “conceptual” is simply a descriptor for art where the ideas matter above all else. That sounds awful too. Ideas are cheap, plentiful, and inconsequential in a way. The Idea is the starting point of any human endeavor, but there’s a reason no one builds monuments to spermatozoa. A lot of horrible art comes from the unfortunate belief that art can be made of ideas.

The Radiance of Mythic Beings

Here’s the thing, the tradition has led to too much great art to ignore. Where would we be without Adrian Piper or Alighiero e Boetti? Where would I be without Gabriel Orozco or Ed Ruscha? I am happy to say “Conceptual Tradition” because its all-star roster is too fabulous to ignore, and it’d be foolish not to learn from their innovations. Right now, there are two examples of conceptual art in Houston that manage to clarify what is great about the tradition by being simultaneously powerful and transparent: Prince Varughese Thomas’ Body Count which is part of the Station Museum’s HX8 and Kendell Geers’ Cardiac Arrest which, for me, is the star of the Menil’s Progress of Love.

We all try.

I don’t think that Geers or Thomas would necessarily describe themselves as conceptual artists; they both cast too wide a net in their multidisciplinary approaches to settle into easy labels. However, the pieces in question are undoubtedly “conceptual.” Neither is dependent on the artists’ skills at crafting things. Both have a certain sculptural presence, but they don’t really engage with the history of sculpture. Were we to apply the traditional language of formal analysis, these pieces would give us little to say. It’s not that formal considerations are absent, they have just been displaced.

The White City.

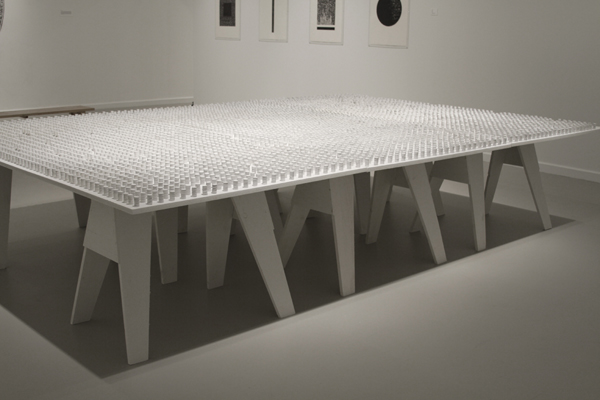

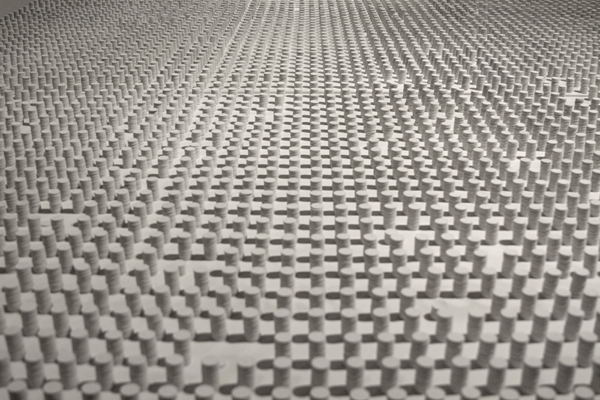

In Body Count, each civilian casualty from the war in Iraq is represented by a penny. There are over a thousand American Dollars in the installation, but each individual life is an insignificant amount. The concept has the potential to move and to infuriate, but it is the specific configuration of the objects that manages to affect us. The stacks of pennies could have been anywhere: on the floor, on the wall, on a platform, but they are lined up on modest white tables. The tables turn the rows and rows of pennies into a scale model. It is an economical way to suggest monumentality without the budget or the pomposity. There are gaps between the rows, one to indicate each month, two for each year. That variation and its visual randomness create a certain topography, along with the implication of scale, the white coat of paint on each penny, and the long shadows cast by the individual towers (no longer stacks) we are not looking at pennies anymore. The viewer becomes the sole presence in a vast necropolis, trapped in a Twilight Zone ending. It is a painful experience, but fascinating enough in its prestidigitation to cause us to linger. Body Count’s success is formal, its power comes not from the ideas themselves, but from the way those ideas interlock and amplify a certain awareness. Its construction is closer to storytelling than to sculpture

Konami Code.

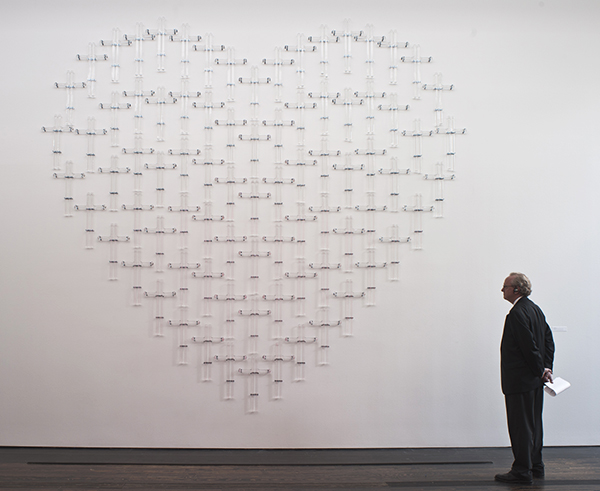

Kendell Geers, or at least the Menil, offers no key for the components of Cardiac Arrest. It isn’t needed; its symbols are significantly less idiosyncratic than Body Count’s. In fact, they are clichés. What Cardiac Arrest offers up is a single wall piece that morphs from cliché to cliché as the viewer gets closer. The viewer’s simple actions, look, walk, are enough to activate this incredible bit of machinery. At first one sees a heart on the wall: that near-universal symbol for the heart rather than the lumpy muscle. Get closer and notice that this heart is made of crosses. Closer still, the crosses now appear to be made of glass. Closer still -real close now- they’re not crosses, they’re batons. Within a few seconds we’ve gone through an incredible array of callbacks: cheap chocolate, cheap sentiment, Blondie, Hot Topic, The Crow, five-o, race riots, schmaltz, fragility, pain, injustice. The symbols have harnessed platitudes to create speed and accumulation. The thoughts multiply, the pulse quickens, Cardiac Arrest is literally exhilarating. I can’t remember the last time I’ve witnessed sequencing this witty.

Theoretical snowflake.

We can make the trips that Thomas and Geers propose because their structures are sound, because they’ve given us everything necessary for the voyage: ships, not just the idea of ships.

HX8 [Houston Times 8] at The Station Museum closes Feb 17

The Progress of Love at The Menil Collection closes March 17

3 comments

The white coat of paint on the pennies prompts me to wonder about the paint’s function. A reference to whitewashing or to white grave markers? Or a desire to seek a more aesthetically cohesive installation? Certainly the whole thing would have had a very different feel if the pennies had been left alone. To an extent, I resent the abstracting effect of the paint. Leaving the pennies unpainted would have given the work a metonymic depth commensurate with its metaphoric presence.

No white paint=no White City. The abstraction opens doors for me.

In Iraq, it is common practice to wrap the deceased in white fabric for burial.