Equipped with a diverse educational background and an eclectic blend of hobbies, Dallas-based artist Rusty Scruby has spent his career exploring themes of music and mathematics through visual art. Employing a variety of techniques, including, most recently, knitting, his work often teeters between the two-dimensional and three-dimensional, as well as between abstract and representational.

A National Endowment for the Arts grant recipient, Scruby has shown his work in numerous exhibitions, and he can be found in several museum collections, including the Art Museum of Southeast Texas and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

We recently discussed his educational journey, his artistic evolutions, and his forthcoming exhibition at Cris Worley Fine Arts in Dallas.

Caleb Bell (CB): You have quite an interesting educational background, including years of studying aerospace engineering. Before we start discussing your work, will you please share a little about your education and tell us why you decided to pursue a career in art?

Rusty Scruby (RS): Yes, it took me a while to figure out what I wanted to do. At the end of high school, I got appointments to Annapolis and the U.S. Air Force Academy (USAFA). I chose the USAFA because I loved the idea of flying and possibly going to space. I soon found out that since I needed glasses, I would never be a pilot. I also realized that the military wasn’t a good fit for me. So, I left the USAFA and started to study engineering at Texas A&M University (TAMU).

I thought I might want to work at NASA eventually. As a student at TAMU, I got a job at Phyto Resource Research. We designed plant-based experiments that were intended to go up in the space shuttle. I was excited that I was on a team of people that sent something into space, but as I started my fourth year at TAMU, I had to admit to myself that I didn’t really like the idea of being trapped at a desk all day. I didn’t love the idea of being an engineer.

As my friends were talking to Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and NASA about work-study programs, I started taking piano lessons. My parents weren’t happy.

I had taken about six months worth of piano lessons when I was little, and then my teacher moved away. I loved playing piano and writing little pieces, but was always told it could never support me and it should only be a hobby. My parents said the same thing about drawing. I drew and played piano my whole life, but in the background. Most of my friends would have been surprised to find out that I was creative.

At the USAFA, after months of not being able to play the piano, I finally found my chance. As we were celebrating the end of basic training, we got our first night off… our first unscheduled time. Everyone was expected to go have a beer and let loose in the designated hall. I, on the other hand, got the help of an upperclassman and snuck off to play piano. Two hours alone with a piano seemed like heaven.

Once I started taking piano lessons again, I finally gave up on the idea of being an engineer. I studied composition for two years at North Texas State University (now UNT). I began making crude videos, trying to visually understand music. Although I would now say I was creating artwork, I was still thinking of it as composing.

Within a few years, I had my first gallery show. Ever since, for about 30 years now, I have been creating artwork that explores the connections between music, math, and art. More recently, I have added knitting to the mix — another thing that I’ve done my whole life.

Rusty Scruby, “Margaret,” 1993, charcoal drawing with Polaroid photos, 29 x 36 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

CB: In that first gallery exhibition, what kind of work did you show? Your photographic reconstructions?

RS: No. In my first exhibition in 1993, I showed charcoal drawings and oil paintings. I did have one drawing, Margaret, where I used Polaroid shots of a tiled floor. I covered the background in the portrait with repeating images. Repetition felt like a way of representing depth, and I started exploring that more and more during the mid 90s with paintings and drawings. Then, I started working with paper constructions independent of images. In 2002, I finally started to combine my paper constructions with repeating images.

CB: As those works of repeating imagery have evolved, to me, they seem to have progressively transitioned from somewhat representational to more abstract. Can you speak to that evolution within the photographic reconstructions?

RS: I guess I have gravitated to more abstraction over the years.

At first, when I was painting and drawing the repeating images, it was very slow work. I enjoyed the process, but I didn’t have time to explore large-scale works with lots of repetition. I had been trying to do everything by hand. I finally decided to use a computer and photographic prints, which allowed me to create pieces with more repetition and be more ambitious. Later, Alan Josephson, a friend who designs software, wrote some custom software for me and I was able to take my ideas even further.

As I was figuring out my process and tools, I was also developing concepts of how music could fit within the world of repetition in which I was working. Searching for the visual equivalent to musical consonance and dissonance is what made my work more abstract or less abstract at different times. I was thinking, and still am thinking about how music, in spite of being so abstract, can evoke similar emotions in different people. Music is an abstract language that penetrates the real world. I wanted to see at what point understanding and recognition broke down through repetition and too much information.

Rusty Scruby, “Midnight,” 2021, wool knitting on poplar wood construction, 18 x 16 x 6 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

CB: Continuing with your influences, how does mathematics play into your work? Thematically, physically, or a little of both?

RS: Definitely some of both. My dad was a math teacher. He had done his master’s thesis on transcendental numbers. When I was a kid and found out what transcendental numbers were, they seemed like a contradiction… something specific but never-ending. It’s almost as if numbers had entered the realm of emotions. Concepts like that have always been part of my artwork, but mainly as a way of inspiring me and not as the subject of the work itself.

However, a few years ago, I was commissioned by TAMU to create a piece for their new Zachry Engineering Complex. They wanted art that dealt with math, science, and technology. They wanted art that a professor could use to help their students interact and learn. I used an image of waves that repeated and shifted over bas-relief forms along a 40 foot length of wall. In that piece, titled Infinitesimals, I was thinking about counting infinity.

I absolutely use math in designing and constructing my artwork. I use geometry in the simple shapes I choose to repeat to create my tessellated surfaces. I usually have numbers and simple calculations covering pages of scrap paper by the time I finish most pieces.

CB: You mentioned that your most recent works have incorporated knitting, something you’ve done your entire life. How did it work its way into your artistic practice? How has that element subsequently evolved?

RS: I started knitting when I was five or six. My grandfather tatted, and my sister, mom and grandmother knitted. For many years, I would just knit seasonally when it got cold outside. When I was in my early 30s, knitting techniques began to influence the paper structures I was working on for art. Some people think that I learned how to create my structures in engineering, however, knitting has been much more of a guide. I love how a long string can turn into a piece of fabric with rich textures and detail… simple to complex.

As a young artist, I created several small study pieces where I tried to incorporate knitting into my artwork. As I started exposing myself to more contemporary art, I noticed the trend to use craft as an art material. I remember going to Miami for the first time to see the art fairs. I was blown away by the amount of knitting I saw. Instead of encouraging me to work more with knitting, I steered clear of using it directly in my artwork. I didn’t want to follow trends and do what others were doing.

Then, Trump was elected President and the Women’s March happened in January 2017. As a way to show support to my female friends, I knit a lot of pussyhats. I think I knit 44 hats that all incorporated pink. Of course, as an artist, each hat had to be unique and knitting hats became its own journey. It also changed something in my thinking, and I started to wonder why I was avoiding adding an element to my artwork that I loved so much.

Finally, I went back to my early studies in art knitting and figured out how to make one of them work. I had been working with a structure I called Cube Network, which is reminiscent of fabric and tiling patterns. However, I saw it as a 3-D structure comprised of three interwoven layers. It provided a limited space to work within. Limitation is a valuable tool for expression, at least the way I see it, but that’s another topic. I had been painting and drawing images onto the surface of the structure. The structure allows me to work on both 2-D and 3-D ideas. Sometimes I superimpose an image across the surface to push things more in a 2-D direction. Other times I explore the 3-D structure and emphasize different aspects of the repeating structure. Knitting creates a countable, repeatable grid, allowing me to plan and map out my works before I make them. Then I’m following my plan for months as I execute it.

The meaning that yarn and knitting have in my artwork has evolved over the past few years – the lockdown years. When we first went into lockdown, being an introvert, I loved it! I’m a bit of a hermit anyway. As most of us were wearing masks and washing our hands constantly, me and my husband, Hampton, noticed that there was a new yarn store opening in Dallas. We drove by and saw that only two employees were inside the whole store. So, for the first time in months, we went into a store! Soon, we started a YouTube channel called The Artful Stitch. Hampton would drive us around the North Texas area as I made videos and showed different local yarn shops, yarn, and prices. People often commented that they felt like they were shopping vicariously through us. We even interviewed a couple of fiber artists, but it was mostly for fun and not very serious. Over that period, yarn shops were one of the first things that connected me back to “normal” life, and yarn still reminds me of that comfort.

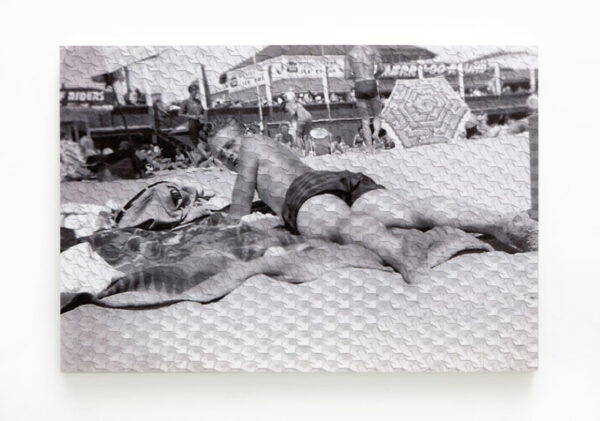

Rusty Scruby, “He Sells Seashells,” 2013, archival photographic reconstruction, 36 x 53 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

CB: Your statement “limitation is a valuable tool for expression” is intriguing. Can you share your thoughts behind it?

RS: If you look at Western music as an example, there are 12 notes that we use. Of course, there are more notes on the piano because those 12 notes recur at different octaves. With those 12 notes, we have decided to limit our musical possibilities. Why not use an infinite number of pitches?

If a piece of music is in C Major, it is written with seven notes. It is heptatonic. In Indian classical music, there are five notes in the pentatonic scale. I believe that these limitations are what give music its clarity and character. The limitation becomes the lens through which the musical ideas are expressed. If you look at the black and white notes and the intervals between, I think of the scale as a landscape that the composition follows.

Years ago, as I was changing from music composition to visual arts, I read the book A New Kind of Science by Stephen Wolfram. It visually explores infinities and the least number of elements that are needed to create an infinity complex enough to contain life.

CB: I know you have an upcoming exhibition at Cris Worley Fine Arts in Dallas. Can you share a few details about it?

RS: Sure, my next show is called Clouds, and I wanted to focus on imagery that is somewhat elusive and changing – like clouds. I have been knitting pixelated images and am interested in how little visual information can be retained while still being representative of the original image.

A few years ago, I watched my mom struggle with memory loss at the end of her life and was struck by how she was able to hold onto her personality. She forgot so much, including who I was, but in many ways she was the same kind and loving woman who raised me. I felt like I was seeing who she was at her core. For this show, I am mostly using images that I have used before. Since I am thinking about loss and limitation, I wanted to have even more familiarity with the images.

As I mentioned earlier, during the lockdown, me and my husband visited local yarn shops all around North Texas. I ended up with a lot of yarn and much of it is from indie yarn dyers. For three of the knit pieces in the show, the yarn comes from Trudy Fedorko of Ewe2Yarn. She is an emergency room doctor who moonlights as a yarn dyer. She was able to create custom colors for me for my two largest pieces. Trudy uses highland wool that is untreated by chemicals and is perfect for colorwork. For other knitters who might visit my show, I use the intarsia technique with fingering weight yarn.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Clouds will be on view at Cris Worley Fine Arts from February 18 through March 25, 2023.

1 comment

Great piece! I enjoyed learning more about Scruby’s background and process.