Artist Kristen Cochran talks with artist Magali Reus on the occasion of Reus’ exhibition at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas.

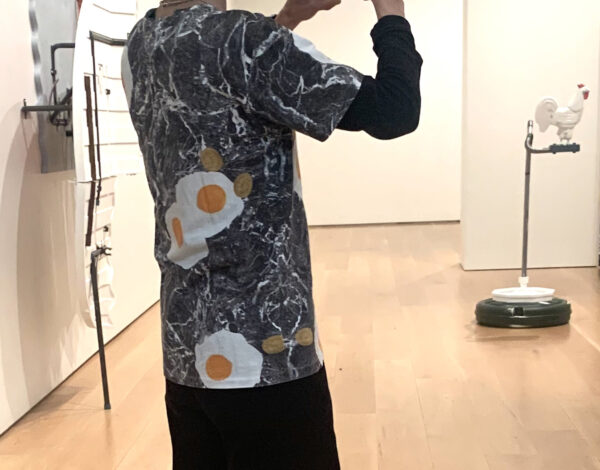

Kristen Cochran (KC): Magali, you were wearing a fried egg t-shirt when we met. It was graphically delicious and perfectly pedestrian. It reminded me of Reagan-era, prophylactic ads in which a freshly cracked egg hits hot cast iron, becoming a tough and rubbery version of itself (this is your brain on drugs)…I’m not a drug user (minus a serious caffeine addiction and the occasional Adderall), but not because of those ads.

Now, after a fallow pandemic, amidst cultural malaise, psychological disorientation and what seems to be a collective need for growth, I’ve discovered mushrooms as a means of regenerating thirsty neural pathways and re-visioning the future. These specimens are also complex sculptural forms with painterly surfaces and feathery armatures.

My interest in your work far precedes content related to mushrooms and soil, though. I’ve been excited about it for many years for its poetic qualities, material complexity, and clever remix of commonplace forms. And with that, I’d like to discuss the title of your exhibition at the Nasher Sculpture Center. Could you talk about the title — how you arrived at it and how it relates to the sculptures and photographs on view?

Magali Reus (MR): Titles tend to sit and simmer for a while. I had lived with this particular one for some time. A Sentence in Soil speaks to an aspect of my thinking about the works in the show: the idea of a sentence, or a writing of sorts, as an act of communication, whether graphic or metaphorical.

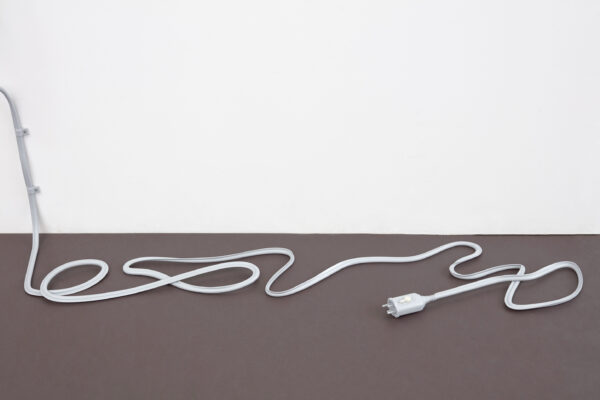

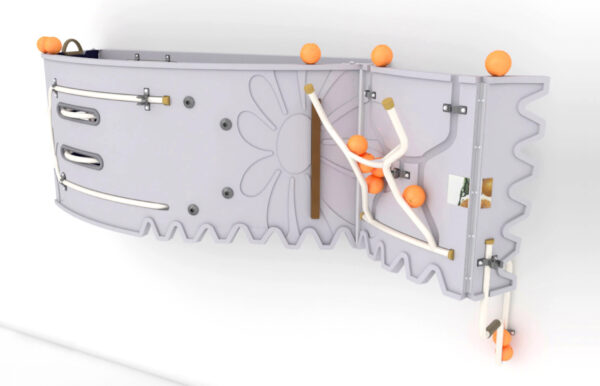

This idea has an important presence in all of the works on display at the Nasher. In the work Clay (Wolf), for example, the graphic language of the soil bag is enlarged and transposed onto the architectural feature of a door using a powder coating process. Transformed, near-abstract script is present in Beetle, where the hanging 3D-printed cord might read ‘EXIT.’ At the cusp of legibility, the cord flickers between semantic meaning and pure form.

Writing and communication is perhaps more abstract in the Knaves series of mushroom portraits. Mushrooms are but the fruit of the fungi, an index of a vast mycelium organism network that remains invisible beneath the ground. Of course I’m interested in the mushrooms and their subtleties of appearance, but underground, in the soil, they communicate via this mysterious threaded structure. As a script, they write sentences in the soil. Soil itself is an enormously complex composite substance of organic and inorganic matter — of which so much still remains a mystery — which produces nutrients to promote growth. Simply, it is the stuff upon which all life on earth depends.

Soil enables a conversation about circulatory processes. I am interested in how this relates to the way we experience architecture: in everyday life our physical bodies enter and exit grounded structures. If we view our bodies as another type of space (which we often don’t), then here, too, is another circulatory experience of consumption. Soil as a circulatory space allows us to process, grow, consume, expel, and compost our foods.

KC: That shifts my perspective higher (bird’s eye) and deeper (worm’s eye) as I imagine hidden networks of script circulating nutritious sentences underground. Meanwhile, architectural orifices and urban arteries conduct human movement above, EXIT signs included.

Let’s dig deeper into soil and clay as they relate to Earthgro, the all-natural mulch. I assumed the main ingredient in Earthgro was manure, and my mind went to metaphors about soil and shit being necessary grounds for cycles of life and death. But after a little research, I’m not sure Earthgro is about (or full of) shit. What is your interest in this particular product and how does it relate to The Clays?

Magali Reus, “A Sentence in Soil,” installation view with “(Mushrooms)” and “Hammock,” 2020-21. Photo: Kevin Todora

MR: Initially, I was drawn to its packaging, and the simplicity and directness of its communication. There is no mystification in the contents, no dressing up or fancifying as a commodity. “Chicken Manure,” “Fill Dirt,” “Steer Manure Blend” — none of these are particularly glamorous or appealing. I was also fascinated by the thought of using chicken manure to grow vegetables for consumption. Do we think about the soil — the manure — in which our vegetables are grown? Imagine for a moment a bell pepper grown in chicken manure! The bluntness of its graphic communication is acceptable as a back door (again, here is the door that the bag’s graphic is transposed onto) to a messy, largely unrevealed or known space to the consumer — namely the agricultural space where the things we eat are being produced.

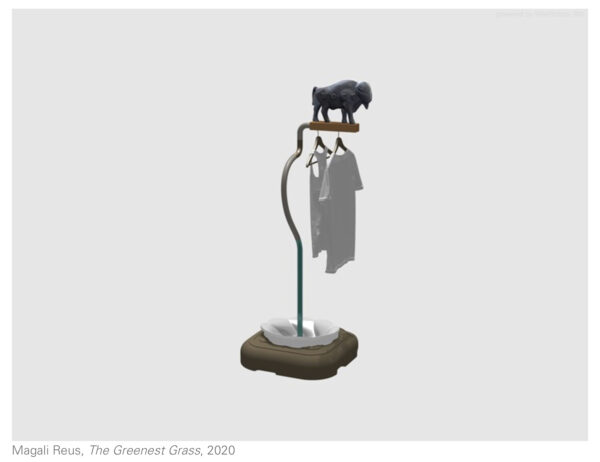

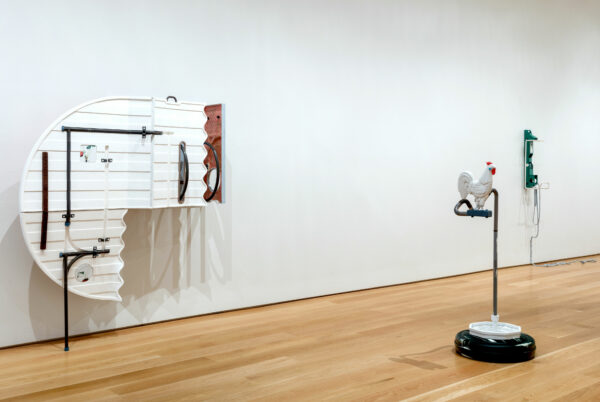

KC: Like many city dwellers, I’m largely removed from the physical realities of plowing, planting, cultivating and harvesting. The closeness and permeability of animal-touching-vegetable-touching-animal (chicken manure – pepper – human), is compelling and strangely fluid. Tell me about the rooster perched on top of Grain of Wind and Apricots? It seems like a different sort of punctuation in these sculptures that sprout upwards.

Magali Reus, “A Sentence in Soil,” installation view with “Knaves” and “Grain of Wind,” 2020. Photo: Kevin Todora

MR: These animals, like the rooster, are taken from a book on windmill weights I came across in a secondhand bookstore. I was drawn in by the simplicity of their rendering. I was looking at the shape of the parasol, as well as the weathervane: both tools constructed for protecting us (from sun, rain) or directing us (warning us of the direction of wind) in nature. It’s an architecture that dictates or scripts how and when we should engage with the outdoors. I wanted to explore this idea of the script, and use these floor-based sculptures to direct the viewer around the space. Therefore they needed to be rendered like friendly companions of sorts, like miniaturized, stilled versions of their animal selves. There’s a tragic-comic nature to these sculptures; bent out of shape, they have a veneer and posture that speaks of the endurance of the unabashed forces of nature.

KC: That’s endearing and relatable, the idea of postures and attitudes bent out of shape. These sculptures also map space (they mark and point) and seem to have been touched by time in the delicious patinas you’ve forged onto their surfaces.

I think of clay as malleable and generative, relating to both figure (body) and ground (time/space). Your sculptural uprights, or The Clays, are rigid; the body of the Earthgro bag has become wall or sign-like, confronting viewers like a billboard or block, but these sculptures are also permeable! Constructed with openings (port holes, peep holes, air vents?) to the outside or the other side. What is the genesis of your interest in Earthgro? Is it a metaphorical device in this sentence? Are The Clays, obstacles? Openings? Both?

MR: Yes, they are rigid, but really their abundance of door accessories — hinges, locks, doormat, door window — speaks more about wanting, about wanting to be opened and closed. The many apertures — peepholes and windows — suggest permeability and circulation.

Magali Reus, “Bonelight (Autumn Glory)” detail seen through “Porthole” in “Clay (Fiber and Leaf),” 2020-21. Photo: Kevin Todora

Magali Reus, “A Sentence in Soil,” installation view with “Knaves” and “Grain of Wind,” 2020. Photo: Kevin Todora

A door is a physical threshold for an architectural experience, allowing (or denying) the circulatory movement of bodies. A door takes its scale in relation to a body, a body which, again, has its entries and exits for the circulatory processing of food. Clay is a soil material that is very much part of another circular system where nutritional substances allow things to grow. So yes, soil is a somewhat metaphorical reference, one that is very much sprinkled onto, or into, all of the ideas I was interested in unpacking in the exhibition works.

KC: The Clays include playful accouterments: a paper plate, a dog dish… How do these sculptural fragments function in the “sentence”?

MR: For the work Clay (Wolf), which contains a welded dog bowl in a recessed space, I wanted to introduce another body and another circulation into the equation — that of a non-human animal body. Of course, the graphic of the Earthgro bag’s content (Chicken Manure) on this work already suggests this, but I felt it needed its own physical space, or the addition of a non-graphic reference to make this idea of the inclusion of a multiplicity of bodies within the system more explicit.

KC: I like the way this recessed space draws me low and close to the work, and how you invite viewers not only to look at (and read) surfaces, but to move around and discover the full form behind, under, and through these wall situated sculptures. Frontally they function something like a strange schematic. In full, they have a sense of totality.

This is also the case in the Bonelight and Beetles works. Sculptural appendages and planar “bodies” are integrated with graphic impressions and legible text. The images of fruit strike me as talismans implying full color fruitfulness. Tell me about your interest in fruit, fruit bowls and the still life.

“Bonelight (Midsweet)” (animation still), 2020. View the video here.

MR: Yes, I was interested in the fruit bowl as a metaphor for thinking about the works for the Nasher in general. I am deeply interested in the fruit bowl because of its multiplicity of reference: aesthetic, art historical, social, geographic, political. I’ve just finished another series of works titled Landings, which I’ll soon show in Los Angeles at Francois Ghebaly Gallery, that continues my exploration.

A fruit bowl is a microcosmic gesture of arranging objects in a vessel. It sets out a space that allows us to feel comfortable with the natural world, which otherwise feels sublime and abstract to us. The fruit and vegetables we buy from the supermarket are made friendly enough so that we’re not threatened by their existence (by their multiplicity, by their profusion, by their ability to grow in nature). Once they arrive back into our domestic spheres, we want to again turn something that was once rampant, wild, and natural into something wholly un-humanly, genetically manipulated; we also want to frame and enclose it into a “still life” setting.

Fruit is both seductive and beautiful; there’s something flirtatious and playfully performative about fruit arranged in a vessel. Laying out the most cosmically perfect purple grape next to a bright yellow banana whose particular shade of yellow offsets the purple-ness is only one examaple.

White plastic tables (with the practicality of their flat-pack construction that allows us to take them outside of the domestic), window awnings (the flirtatious stripes on the skin of the Bonelight series you’re referring to use this as a reference), and fruit bowls have something in common: they speak of us carefully relocating ourselves outside of the domestic sphere, into nature. For a picnic, there’s a posturing involved. We want to consume our food outdoors, to revert back to our ancestors who hunted and gathered and consumed their foods exposed, in nature. While we feel the desire to step outside, we continue to feel the urge to frame it. We set a space onto the tables, ritualistically laying out cloth, plates, cutlery, and other accouterments. We set a scene, one that is again more about its orchestrated aesthetic presentation, a staging of the idea of the natural, than about the real, “true experience.”

KC: I opened this dialogue with a note about your fried egg t-shirt. I thought it might be appropriate to close our conversation in the same manner. In A Sentence in Soil, there’s a newer series of photographic works, the Knaves. Could you talk about how Texas t-shirts made their way into this work, and, if you’d like, about mushrooms as “disobedient” forms?

MR: Yes, and these t-shirts have become part of yet another cyclical journey. The exhibition was supposed to open in 2019, but was delayed due to the pandemic. After my first site visit to the Nasher, I went on a small car journey down south to San Antonio, passing through lots of towns along the way. In Dallas, I went to a big thrift store and ended up purchasing a light pink t-shirt with green graphics celebrating the corn harvest season. This t-shirt can be seen in the background of the work Knaves (Cassino), currently showing at the Nasher.

During lockdown, as a way of anchoring my location to Dallas, I decided to use this t-shirt as a backdrop for the portraits of the fly agaric mushrooms I stumbled upon during my pandemic time in Holland.

Later, back in London, as winter approached, we found ourselves in yet another lockdown. I wanted to continue the series, and these Texan t-shirts celebrating agriculture or nature in one way or another ended up continuing to be a part of the images’ backdrops. Purchasing a range of them on eBay and other websites, I ended up with quite an impressive library of shirts. Packing for my latest trip to Dallas, for the opening of my exhibition, I actually decided to bring that light pink corn harvest t-shirt along as a good omen. Like the other works, it felt appropriate to make it part of a kind of ritualistic transformation. From one physical body, to a store, as part of a recycling process, to another body, another continent, finally extended into the flattened space of photography as seen in Knaves (Cassino). Something about traveling in this new guise to its place of origin alongside its physical referent (which I bought in my packed suitcase) seemed a perfect resolve of a long, frustrating, but equally inspiring two-year journey.

Magali Reus: A Sentence in Soil is on view through October 9, 2022 at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas.