Para leer este artículo en español, por favor vaya aquí. To read this article in Spanish, please go here.

The Rio Grande Valley’s artistic scene is in recovery, however precarious it may be. This comes as a communal effort, with the older generation of artists mentoring young talent, and the younger generation starting to test out their wings in local exhibitions. The experience of witnessing this rebirth is like watching a multi-generational family celebrating the first steps of a toddler — something common and precarious, but also joyous. This is an experience that transcends cultural boundaries, but simultaneously, it is something unique and defining for South Texas. The artistic environment here is not a product of capitalistic competition, but something like sibling rivalry — the kind that propels families onward and outward. This aspect of the community was described to me by an artist I had recently reviewed, Ben Muñoz: this community is familia.

All the galleries in this region are artist’s studios that have additional exhibition spaces. These are distinct among other artist-run galleries in that the spaces are divided between an individual’s work space and shared exhibition spaces. These exhibition spaces also function as community spaces where workshops, classes, performances, and artists’ markets are held. Economics factor into this model — according to the U.S. Census, the 2015-2019 median household income in Brownsville was 62.4% of that in Texas overall. Buying art in this region is a matter of community rather than status, and the art market here is not collector-driven, but artist-driven. As such, the gallery exhibitions in this region are not held primarily to sell art, but to share art within the community and beyond, as familia.

****

Border Impressions at La Chicharra Studio in Brownsville, through January 3, 2022.

La Chicharra Studio is a new gallery and community art space that opened in downtown Brownsville in July of this year, joining more established spaces like Puente Art Studio and Arte Vivo. The owner and director, Ruby E. Garza, who received her BFA from University of Texas Rio Grande Valley in 2019, is an artist who works with various media, including printmaking, painting, and pastels. She learned about operating a community arts center while working at the Carlotta K. Petrina Cultural Center, a major cultural hub for the Brownsville arts community, which unfortunately has discontinued its visual art exhibitions since the COVID-19 pandemic. Garza’s new venture is a part of an effort to revive the visual arts scene in the city after the devastating effect of the pandemic on Brownsville arts in the last two years.

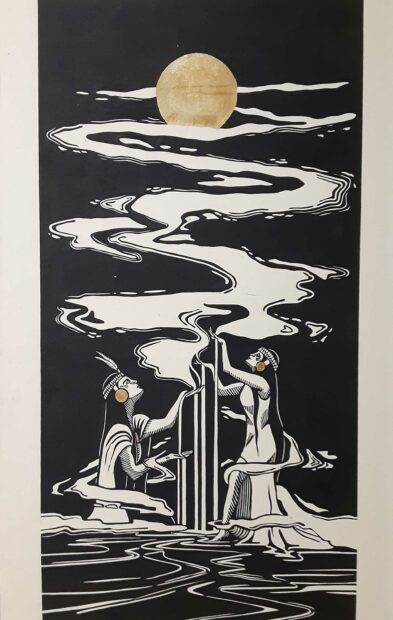

The space’s current show is an inaugural printmaking juried exhibition and is titled Border Impressions. It was juried by Sergio Sánchez Santamaría, an internationally-renown Mexican printmaker working in Mexico City and Tlayacapan, and the winner of the competition was Cristina Piecuch, who graduated from Grand Valley State University in Michigan and is participating in the Art Business Incubator South Padre Island’s (ABI SPI) Art Residency Program. She won for her undulating, dream-like print Wallpari, which means “creation” in Quechua.

Cristina Piecuch, “Wallpari,” 2021, Linocut with gold leaf, 32 x 20 in. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright Cristina Piecuch.

The exhibition is an ambitious effort to showcase both young local artists and those participating from outside of South Texas. In this show, I was personally struck by the breadth of young artistic talent in the region. For instance, many of the artists are UTRGV students and recent graduates; they studied with Reynaldo Santiago and Noel Palmenez, who have been teaching printmaking at the university. In this inaugural printmaking competition, the works of young, local artists also showcased the wide breadth of the melding influences of the U.S.-Mexico border.

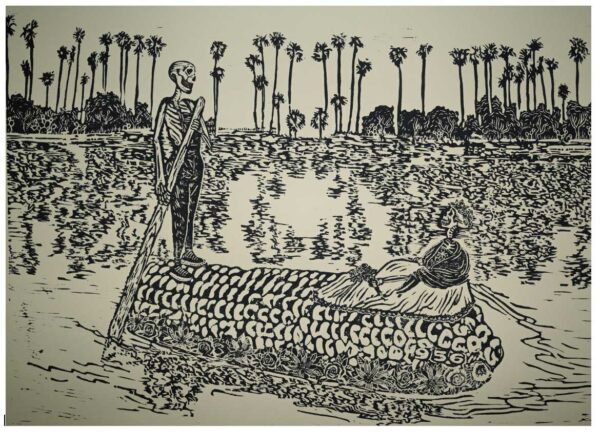

Miriam Celedon, “El Reencuentro/The Reencounter,” 2021, Linoleum print, 18 x 24 in. Courtesy La Chicharra Studio. Copyright Miriam Celedon.

The winner of the Audience Choice award was Miriam Celedon’s El Reencuentro/The Reencounter. The work is a linoleum print in the style of a history painting, depicting a pair of skeletons on the water who are lovers, as told by their undead gaze. One is in overalls and steering a cob of corn that surreally functions as their boat, and another is in a dress and shawl, holding a bouquet of flowers and wearing a band of flowers on its head. A curtain of tall palm trees provides a backdrop, and these trees are reflected in organic scribbles across the water’s surface. This is South Texan impressionism as a print.

Ana Luisa Pérez Garza, “Chepina,” 2020, Woodcut, 18 x 17.5 in. Courtesy La Chicharra Studio. Copyright Ana Luisa Pérez Garza.

Ana Luisa Pérez Garza’s woodcut demonstrates a deep admiration for Northern Renaissance printmaking. The work amasses volume from fine details of lines, contours, and hatching in the style of Albrecht Dürer’s prints, but the subject matter is contemporary: a pet dog, Chepina, is shown sitting on her owner’s lap and with a halo around her head. Garza repurposes classic Renaissance style and subject matter for today’s mundane subjects.

Michel Flores Tavizón, “Ni de aquí, ni de allá,” 2021, Woodcut, 22 x 24 in. Courtesy La Chicharra Studio. Copyright Michel Flores Tavizón.

Michel Flores Tavizón alludes to Frida Kahlo’s The Two Fridas with her own self-portrait. Like in Kahlo’s work, in one seated image Tavizón is wearing a traditional Mexican dress, but the other shows her in contemporary clothing, with a t-shirt, skinny jeans and chucks. On either side of the two images are eagles perched on a cactus, symbolizing her historical roots in Mexico. Tavizón’s composition is placed in a shallow foreground and closed in by a grid of lateral fencing that alludes to her minimalist aesthetic, which is the launch point of her surrealist self-image. The tight fencing also refers to the U.S.-Mexico border, and Tavizón’s complex negotiations with identity in this region is captured in the title, which means “Not from here, nor from there.”

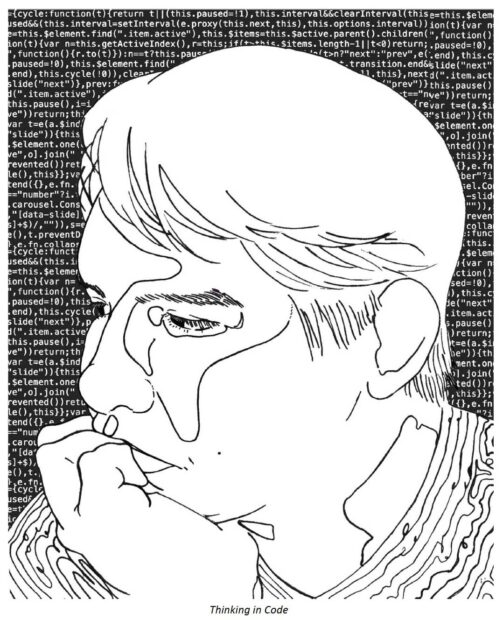

Carla Santillana, “Thinking in Code,” 2021, Screenprint, 18 x 20 in. Courtesy La Chicharra Studio. Copyright Carla Santillana.

Carla Santillena’s screenprint, Thinking in Code, has a great sense of linear control and directionality; it depicts a portrait of a young man deep in thought. He is surrounded by JavaScript code, a wall of language only fully legible to circuits and machinery. The loose directionality of his brushed-back and cut hair, the clenched hand against his lips, as well as the topographic lines on his shirt all help place his head into a gentle but intense focus.

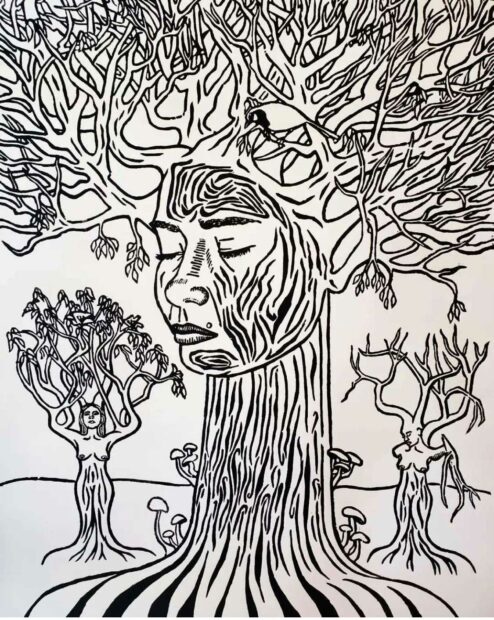

Jocelyn Torres, “Transfiguration/Transfiguración,” 2021, Print, 15 x 20 in. Courtesy La Chicharra Studio. Copyright Jocelyn Torres.

In Transfiguration, Jocelyn Torres has created a fantastical landscape of her self-portrait as a tree coming out of hibernation. This portrait’s long, extended neck blooms into her face; her eyes are closed in contemplation, and her hair is a rising series of crisscrossing branches with buddying shoots at their tips. Mushrooms peek at the base of her neck, but she’s in a state of growth, her bristling, busy branches extending upwards every which way.

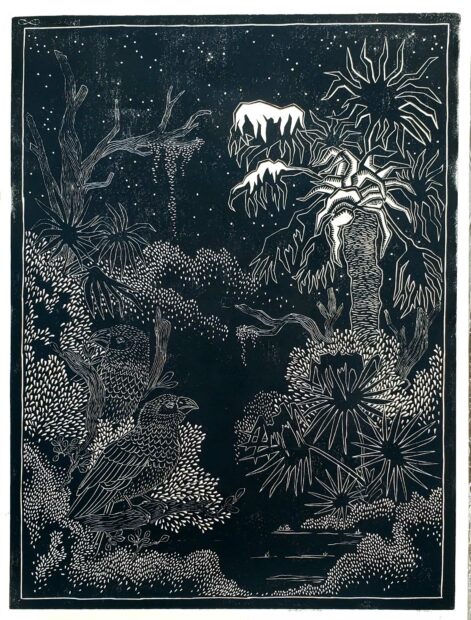

Cecilia Sierra, “El Monte,” 2021, Linocut relief print, 18 x 24 in. Courtesy La Chicharra Studio. Copyright Cecilia Sierra.

Cecilia Sierra’s El Monte encapsulates the experience of visiting Sabal Palm Sanctuary in Brownsville, a tropical South Texas nature reserve and bird sanctuary that protects one of the few remaining Sabal Palm forests. The plants in Sierra’s piece have much to say — the palms, shrubs and foliage drape, extend, spread, and condense into directional patterns that spell out a larger vista of South Texas landscape. A pair of groove-billed ani, a distinct South Texas seasonal resident, nestle themselves into the enveloping foliage, alluding to both the comforts and the power that draws South Texas natives back home to this region.

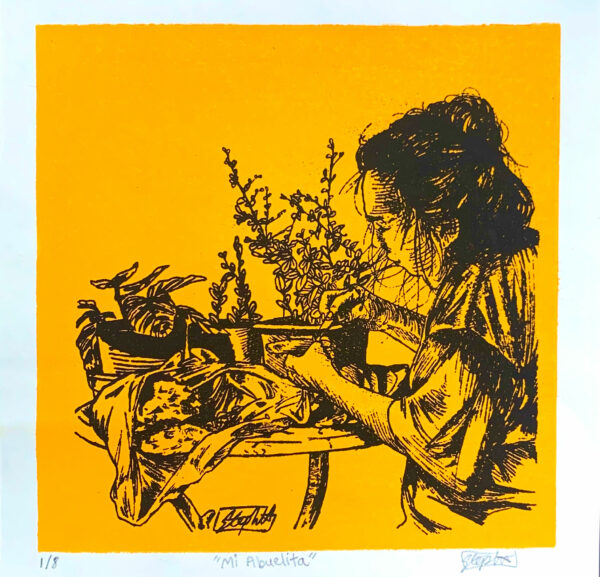

Stephanie Hauser, “Mi Abuelita,” 2021, Screenprint, 8.5 x 9 in. Courtesy La Chicharra Studio. Copyright Stephanie Hauser.

In Stephanie Hauser’s Mi Abuelita, a woman who is trimming through a plastic bag full of nopales hunches over a table that holds an arrangement of small planters with herbs. It’s a beautifully poignant portrait along the lines of Vermeer, with the woman unaware of our gaze. Her hair is strewn about her face as she hones in on her task of feeding and healing her family with the greens of South Texas’ brushlands. With the brilliant color backdrop, Hauser elevates the everyday scene into the extraordinary. As is the case for this particular work, Border Impressions as a whole is about reconfiguring historical visual language and remixing it with contemporary imagery that’s unique to the Rio Grande Valley.

****

From Life at Arte Vivo in Brownsville, through January 6, 2022.

The owner of Arte Vivo Gallery is Teodoro Estrada, an artist with deep local roots whose mid-career survey took place at the Brownsville Museum of Fine Art in 2021. He founded the gallery five years ago after his retirement from the local school district, where he supervised its art programs. He built this gallery to bring more visibility to art in downtown Brownsville, and before COVID-19, he had also organized an art walk, Brownsville Noche de Arte. Newly reopened, the space stages weekly poetry readings, hosts a local art market, and has plans for four exhibitions per year. The current exhibition, From Life, is one of the first shows Estrada has organized since the onset of the pandemic. It is a two-person show of master printmakers from South Texas, Omar González and Jessie Burciaga. Both artists are recent MFA graduates from the University of Texas at San Antonio.

Omar González is a printmaker based out of nearby Kingsville, and he is an adjunct lecturer at Texas A&M University-Kingsville (and my current department colleague). In this show, he displays his command of various printmaking methods. For González, his technique is adjusted to fit the subject matter and the appropriate feeling of each work. The pieces on display demonstrate a theme of family life, particularly focusing on the role of women in family units. His compositions range between historical and photographic.

The theme of González’s works here is women and gender. All of González’s prints on display are from the last year or so, with the exception of a piece from 2014. In this earlier piece, the figure of a woman dressed in charro is playing a violin, and at the tip of the musical instrument is a miniature figure of a dancing young woman. As in González’s other works, here his women are powerful, thinking, feeling, living subjects.

González’s smaller linocuts convey a sense of warmth, solidity, and stability that’s covered in part by their evenly-spaced and design-oriented cuts with bold lines. His larger linocuts, such as his Origin of Connection, shows off a multitude of patterns and textures, such as lace. González’s prints nest a complex set of connections between various material textures that map out the dynamics of human relationships in South Texas. Additionally, his drypoints communicate uncertainty through their delicate and intricate sensibility. In Her Path, the piece’s hatchings, swirls, curls, and sponge-like textures appear and disappear to create a sense of displaced and unsure depth.

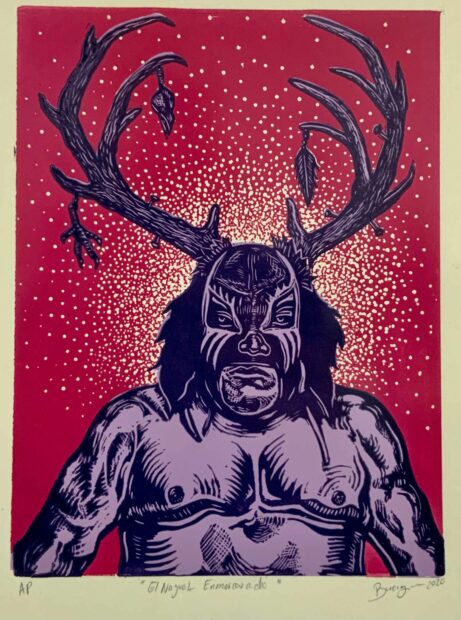

Jessie Burciaga, “El Nagual Enmascarado,” 2020, Relief print on paper, 14 x 11 in. Courtesy Artevivo Art Gallery. Copyright Jessie Burciaga.

Jessie Burciaga’s works are symbolic portraits, oftentimes combining both animal and human elements. Many of his works are fictional characters pulled from lucha libre — Mexican professional wrestling.

Jessie Burciaga, “Corazón Espinado,” 2021, Woodcut print on cloth, 54 x 39 in. Courtesy Artevivo Art Gallery. Copyright Jessie Burciaga.

El Nagual Enmascarado (2020) is a relief print on paper. The piece has a magenta background and a deep purple outline, showing the upper torso of a luchador wearing a mask decorated with jagged teeth. Deer horns rise out from either side of his head. He is a nagual, a guardian spirit taking the form of a beast, from the mythical tales of indigenous Mexico. A head, a claw, and a feather hang from the horns, warding off illness and despondency, as a spray of white forms a protective halo orb around his powerfully set body. From the depths of despair and isolation during a global pandemic, this nagual guards, calms, and cleanses the mind and the soul.

Burciaga’s largest work in the show is Corazon Espinado (2021), a woodcut print on cloth. The lined face of a heavyweight fighter stares down the viewer with his head slightly cocked, as a thorny vine snakes its way out of an open, heart surgery wound on his chest and loops into a crown around his head. A thorned Mexican sacred heart burns from his left breast, with rays of blood branching out across his skin. It’s a work that makes you freeze in your tracks the second you see it. This is a modern day allusion to Christ, and a contemporary visual rendition of the Mexican folk and Catholic roots of South Texas. It alludes to sacrifice, death, and resurrection — themes that strike a harsh but necessary chord in today’s communities, and in our acts of rebounding and rebuilding.

****

Harlingen Art Night, Downtown Harlingen, every last Friday from 7-10 PM.

Diálogo at Titan Studio in Harlingen, through January 20, 2022.

During Harlingen Art Night, most of the action is situated around tables along A Street in the city’s downtown, with vendors selling local handmade goods including candles, jewelry, knitted hats, and art. Here, you will find artists that sell their smaller works and editions to the larger community; Jessie Burciaga was tabling doing just that. Some nearby shops also participate; at a café, Girl of All Trades, I met the local watercolor artist, Nicholas Angel, who was selling their gentle and deeply personal watercolors alongside their homemade herbalist goods. A space similar to La Chicharra and Arte Vivo in Brownsville is Carla Hughes Art Gallery, which is also the artist’s studio and hosts monthly exhibitions with openings that coincide with Harlingen Art Night. There are two spaces in Harlingen run by artist couples: Titan Studio and Comminos Studios. On this evening, I had a chance to visit Titan Studio, as they had organized an exhibition as a part of the Art Night.

Titan Studio is run by Aleida García and Brian Wedgworth. García creates mixed media jewelry, and Wedgworth is a sculptor who builds metal 3D works in varying sizes. Their studio also functions as a hub where local artists come together, meet, and connect while making and exhibiting art.

Aleida García, “Talisman,” 2018, Yellow quartz, quartz crystal, sea urchin quill, circuit board, sublimation print on aluminum, copper, nu gold, stainless steel bolts, and sterling silver; 6 x 3 in. Courtesy Titan Studio. Copyright Aleida García

A number of García’s works could be seen displayed along the wall nearest to her studio. An exemplary piece is a necklace she made using the electronic circuits from her mother’s old calculator. The work is a combination of folk, cyberpunk, and art deco: her interest in native healing practices comes together with ruins of technology and family ties. The form of the piece brings together the mechanical lines of circuit boards along with delicate outlines of metal and carefully placed pendants made using quartz crystal. A warm, unevenly rounded stone with a partially-polished surface is connected to rectangular metal arms that extend out into a chain. In this composition, the colors of obsolete circuits seems bright, worn, and familiar, like an old friend. The work is a brilliant matriarchal portrait.

With the space’s exhibitions, García negotiates between her dual interests in representing local traditions and showcasing digital art. At the moment, she does so through two separate venues — García is the director of the San Benito Cultural Center Museum, where she has currently organized a group exhibition on the figure of Virgin of Guadalupe, called Castilian Roses in December. For Titan Studio’s experimental exhibition space, she is particularly interested in showing new media works (which are traditionally uncommon in this region), in order to create wider discussions about media art practice in the Valley. This is the case for the studio’s current show, Diálogo, featuring art by Dominic J Sanchez and Brian Wedgworth.

Dominic J. Sanchez, “Triptych of Movement,” 2020, Film installation, 30 min. Courtesy Titan Studio. Copyright Dominic J. Sanchez.

Dominic Sanchez’s Triptych of Movement was projected in the gallery as a part of the exhibition. In the piece, three videos have been combined into a single-channel video, stacked in a vertical orientation. The work is an interwoven series of interviews between Sanchez and five people with varying African and Afro-Caribbean diasporic roots. Channels continue switching throughout the 30-minute work between three locales: South London, Belize City, and New York City. Each interviewee shares their migratory paths over the years, their travel’s relationship to their identity, to the languages they speak, and the different ways in which they are perceived in each place they have called home. In particular, there is a focus on the idea of code switching, of changing one’s mode and manner of communication based on who they are interacting with. The film also deals with various perceptions related to Black diasporic identities as linked to levels of melanin, accents, colloquialism, and dealing with racial aggressions. The work is ultimately about unpacking the idea of belonging and unbelonging through examining the connections between diverse migratory paths of the Black diaspora. The work harkens to some of the earliest examples of video art from the 1970s by pioneers like Raindance Corporation.

Wedgworth’s sculptural works are created using scrap metal from the region’s plentiful oil and gas industries. His pieces bring into view the byproducts of fossil fuel consumption, and transform them into objects of contemplation and reflection on form. Critic Nancy Moyer, who has been writing for years in the region’s newspaper, The Monitor, has warmly reviewed the artist’s recent career survey at UTRGV’s Performing Arts Complex in Edinburg.

Brian Wedgworth, “Untitled,” 2021, LED, found objects, and steel; 8 x 3 ft. Courtesy Titan Studio. Copyright Brian Wedgworth.

Titan Studio’s show begins with Wedgworth’s work Untitled, which was shaped by his months-long chemotherapy treatment in San Antonio three years ago. During this difficult time, he created a hand-sized dome out of metal, with piston-like pieces jutting out from the top — a reflection of the biological battle that took an immense toll on his body. Today, its meaning has changed in the midst of a global viral spread, and Wedgworth made a larger work out of this piece. He floated this specimen in an industrial metal ring that’s been underfitted with eerie blue and purple LED lights and backed by an oxidized metal panel that stretches horizontally to imply the extent of the contemporary health crisis. This work greets visitors at the entrance of Titan Studio, reminding us of the precarity of social gatherings in exhibitions.

But the Rio Grande Valley is a hopeful place. Wedgworth’s monolithic new work, Oculus, has been installed in the Monroe Street Sculpture Park, diagonally across the street from Titan Studio. This piece connects the studio to the larger community. Its tall, massive frame has been welded to form a crescent-shaped crevice near the top, into which a metal ring has been fitted. The tension between the ring and the tips of the crescents that hold it in place encapsulates the relationship shared by the studio and the community: the expanding ambitions of the studio and the community that holds it up in its place.

Brian Wedgworth, “Oculus,” 2021, Steel, 12 x 3 x 2 ft. Courtesy Titan Studio. Copyright Brian Wedgworth.

In South Texas, Titan Studio raises the question of the area’s future in relation to its complex history of indigenous, Spanish, Mexican and American roots. Between the space’s attempt to merge indigenous subjects and new media and the show’s repurposing of regional industrial waste and consideration of new migratory moving images, it is an encapsulation of the issues the community is turning over as it remakes itself after almost two-years of the pandemic. With this, South Texas’ artists and artist-run spaces are projecting familia into an uncertain future.

Exhibition dates for nearby galleries and museums not mentioned in this review:

Influenced: New Work from Mara Bentley at Carla Hughes Art Gallery in Harlingen through December 30, 2021.

Manuel Miranda: El Poder de la Mirada at Puente Art Studio in Brownsville through January 22, 2022.

Castilian Roses in December at San Benito Cultural Heritage Museum through January 21, 2022.

Ray Smith: Pansy Pensamientos at Brownsville Museum of Fine Art through January 28, 2022.