Ray Smith’s exhibition at the Brownsville Museum of Fine Art is a letter home to South Texas. The show revisits Smith’s 2006 retrospective, Painting as a Territory, which took place at the same location as the institution’s inaugural exhibition, both of which were curated by Omar-Pascual Castillo. The earlier show established Smith’s bonafides in multiple areas: as an inheritor to the Spanish classical tradition of painting in the vein of Diego Velázquez; as a vehicle of the work of Mexican muralists David Siquieros and José Clemente Orozco; and as a Postmodernist figurative painter of the 1980s, alongside Julian Schnabel and Francisco Clemente. This new exhibition recontextualizes Smith’s older works in the Spanish-Mexican colonial tradition of ranching, and grapples with notions of gender in his work, as relating to the artist’s roots in South Texas.

The title of the exhibition, Pansy Pensamientos, is an ode to Smith’s mother, to whom this show is dedicated. She is the nexus of the two themes in the exhibition: open ranching and gender. Pansy is the great granddaughter of Francisco Yturria, who in the early 19th century married in to the Treviño family, which was one of the original colonizing families of South Texas. Through this marriage, he came to own a portion of the 18th century Spanish land grants given to the family. Today, the Yturrias are the only family of Mexican descent to retain their ownership of large Texan ranches dating back to the 19th century. The Yturrias were one of the architects of the South Texas as it stands today, a fact that becomes obvious as you navigate through Smith’s exhibition and the Brownsville Museum’s space. The show turns the question of territory inward to “here,” to Smith’s origins in Brownsville.

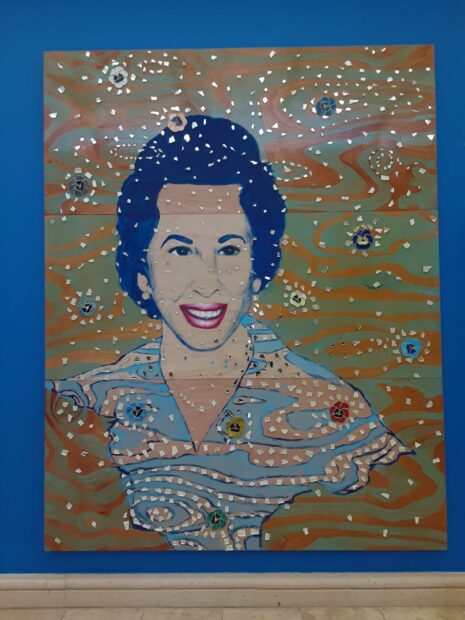

Pansy Pensamientos (2021), oil and glass on wood, 106 x 84 in. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright Ray Smith.

The show begins with a work placed in the center of the main hall of the museum — a portrait of the artist’s mother, Pansy Yturria Smith — flanked on either side by folding screens painted with pansies. In this piece, her image is painted onto three large conjoined wooden panels that are primed only with clear varnish, a stylistic touch Smith is known for, considering his interest in the materiality of art objects and tools themselves. The color of the wood serves as the warm skin tone of the figure, a photographic reproduction outlined with cool blue tones. A number of dainty stained-glass pansies and small broken mirror pieces surround the figure, and the overall effect is that the Pansy’s portrait pops and sparkles — it is a joyous painting that celebrates a keystone in Smith’s life.

Pansies (2021), enamel on mirror mounted on steel frame, 9 panels, 85 x 37 in. per panel. Courtesy Ray Smith Studios.

Pansies (2021), enamel on mirror mounted on steel frame, 9 panels, 85 x 37 in. per panel. Courtesy Ray Smith Studios.

The mirror screens on either side of the portrait have four and five vertical panels respectively, mounted on plywood and encased in metal frames. Smith painted a pair of pansies in varying colors on each of the panels on the left-hand screen, while the right piece has only one pair of dark purple pansies that are surrounded by panels painted in a pattern to suggest shattered glass. Showing two sides of a subject is a consistent theme within Smith’s work, and as a spectator in front of these mirrors, one can see Pansy Yturria Smith as either colorful and bright, or as dark and broken. It is a call to the community to reflect on her legacy, and the role of women in South Texas.

Surrounding this set of works in the main hall are three large-format paintings Smith made in the early 2000s, each depicting a bedroom. As previous writers on Smith’s work have noted, there is an obvious Oedipal theme in this arrangement — they allude to the artist’s childhood; a filial pair of dogs occupy one painting, a series of interstitial, dimensional portals fill another, and a pair of explosive mushroom clouds rise in the last. The wide range of South Texas mother-son relationships may be encapsulated in these juxtapositions.

The museum’s North Atrium Gallery is dedicated to the memories of Sandra and Fausto Yturria Jr. Here, Smith’s work harks back to the tradition of open ranching that began in 1766 with the arrival of Capitán Blas María de la Garza Falcón, the first Spanish colonizer and ranchero in South Texas, who came under the order of José de Escandón, the first governor of the state of Nuevo Santander. Falcón’s establishment of the Santa Petronila Ranch near the Nueces River was the beginning of ranching in North America. This was years before the arrival of Anglo settlers with Stephen F. Austin in 1825, and also years before the beginning of what we now think of as cowboys, who learned their ranching skills from Spanish-Mexican vaqueros.

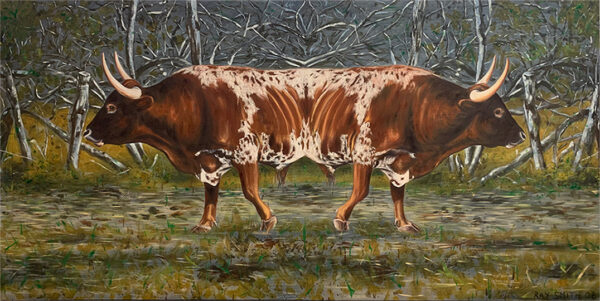

The gallery begins with a venture out into the thicket of the atrium. The first work is hidden behind an enclosed wall partition that is easily missed. Wandering into the small nook, you find a life-sized painting of a startled bull. The installation recalls how one might imagine the experience of stumbling upon a wild animal in the brush.

Upon a second look, this painting is a mirror image of a front half of a bull, bilaterally divided, with each of the figure’s two heads setting off into opposite directions. It emerges out of the brush at a brisk pace, its hooves treading through thick, muddy pasture. The close backdrop of the thicket pushes the bull forward toward the viewer, again giving us the experience of a surprise encounter. The animal’s quick rhythm and energy is captured in the choppy details of the brushwork and the piece’s complementary colors, both of which give off a sense of unease.

This isn’t the bull found in Francisco de Goya and Picasso’s works; this bull is uniquely South Texas. The Criollo bull of Spanish stock, which was relocated to and bred in the open ranchos of the New World, was quick, adaptable, and hearty. This original Criollo cattle evolved into Texas longhorns, and it is this tradition and history that Smith’s work seeks to communicate. The story of this listless, wandering bull sets the tone for the rest of the gallery, and pushes the viewer back out into the space.

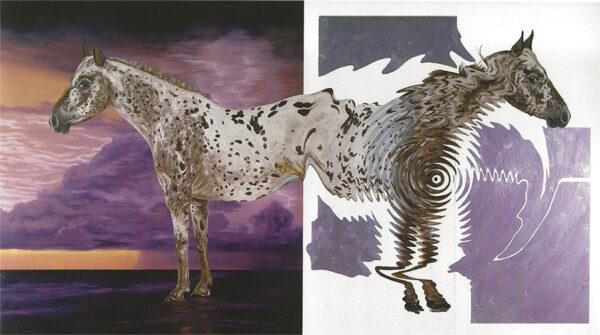

On the immediate, opposite side of the false wall is a painting on four unprimed wooden panels of an Appaloosa horse. While the animal is mirrored in a way very similar to Smith’s bull, the right side of the horse’s reflection is distorted, and the painting’s scene is not naturalistic.

The horse on the left is wary, and it looks on guard at the viewer. It is a horse of the New World, born in the open landscapes of South Texas. It stands against the backdrop of an incoming storm, which is complete with lavender purple clouds, curtains of rainfall, and sketches of lightning. The mirror image on the right side looks to be rung through an early 1990s ripple effect — a sonic boom across the picture’s space-time. In this work, this horse exists between representation, fiction, and history, ringing outward into the rest of the gallery space.

Caballo y Lágrima Celadon, (2020), raku ceramic, 34 x 26 x 26 in. , 31 x 31 x 31in. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright Ray Smith.

Pulling the viewer further into the exhibition are swimming sea horses that arise out the depths of the gallery’s concrete floor. These ceramic creatures, each covered with a different glaze, straddle the line between abstraction and figuration. They are material evidence of the displacement and reconfiguration that occurs in borderlands between the United States and Mexico, and show wide-ranging influences, including East Asian celadon and indigenous micaceous pottery. They swim in and out of the gallery floor alongside the steps of the visitors, like motions across a Gulf Coast dreamscape.

Caballo y Lágrima Plata, (2020), raku ceramic, 34 x 26 x 26 in. , 31 x 31 x 31in. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright Ray Smith.

Upon following these seahorses, viewers reach the largest painting in the gallery, Concepción (2003). The work is an unencumbered vista of Texas’ open range ranch lands, painted on 12 wooden panels. Each panel is painted in a monotonal color palette, representing a different hue within the state’s expansive, rolling landscape. Smith’s work recalls the wide-open stretches of Texas’ vast brushland, before their disappearance behind fences and their sullying by the oil and gas industries.

Other pieces in the room include paintings of dogs appearing as skeletal or distorted forms, and another folding screen mirror painted with pansies, which connect the gallery’s memories of the South Texas landscape and environment to the main hall, and to Pansy Yturria Smith.

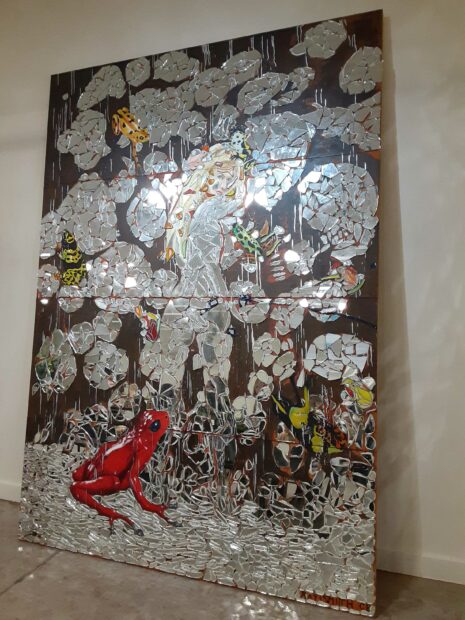

On opposite corners of the last gallery in the exhibition, there are two additional symbols of South Texas: a mirror image of a naval aircraft carrier on the move in Regatta (2003), and a mirror images of a gun cabinet in Ghosts (2003). Corpus Christi is one of the major naval stations in the Gulf of Mexico, and because of the popularity of hunting in this rural region, gun cabinets are a familiar feature in many homes. Between these two works, however, there are myriad paintings with broken mirror pieces covering the surfaces, some of which come together to form figures of nude women in ecstasy or deflection. If the filial dogs in one of Smith’s bedroom paintings refer to the historic dream-like ranch lands of the “good” son, this room is the opposite, representing another’s nuclear explosions.

Smith’s series of paintings with broken mirror pieces dates back to 2009, and unlike the delicate portrait of Smith’s mother, these works are violent, hungry, and listless. The disorientation of these works represents shattered dreams, histories, bodies, and realities. They are fantasy and artifice — the end point of the ranching culture as memorialized by Smith’s other body of works.

The last painting in the gallery indicates a possible redemption of the onslaught of changes in South Texas. It references the SpaceX launch site, which is located in Boca Chica, 20 miles from Brownsville. The initiative, a project of tech entrepreneur Elon Musk, is beginning to expand and brings with it high economic expectations for many of the area’s residents. Smith’s painting is hopeful, with long, bright trails of burning rocket fuel headed up into the skies, which are filled with stained glass stars and billowing swirls of mirror shards.

Ray Smith’s work is important for South Texas, as it represents the foundations of the region. It also represents our contemporary dichotomy — just as the romance of the open vistas and brushland of early Spanish-Mexican ranches have gone by the wayside today, so too has the notion of the “good” ranch woman and its biological determinism. Rather than being portrayed as saints or objects of desire, women now paint a more complex picture of life in South Texas.

Clarissa Martinez, Lazos de mi Ciudad (2021), painting on wood panels. 5 x 5 x 5 ft. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright Clarissa Martinez.

Miriam Celedon, Lazos de mi Ciudad (2021), painting on wood panels. 5 x 5 x 5 ft. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright Miriam Celedon.

In the walkway extending from the adjacent Linear Park to the museum, a number of painted wooden palette boxes have been commissioned in partnership with the museum for an outdoor exhibit called Lazos de mi ciudad, installed in March of this year to celebrate Charro Days, an annual Brownsville Lenten celebration in collaboration with the city of Matamoros, Mexico. The works are portable murals that describe the experience of living at the border. Participating artists include Eduardo Del Angel, Josie Del Castillo, Miriam Celedon, Ruby E. Garza, Jonathan Hernandez, Monica Lugo, Clarissa Martinez, Sam Rawls, and Alejandra Zertuche. Each artist pictured life in South Texas, showing everything from women dancing to conjunto music in Martinez’s work, to the confluence of burgers and tacos across Matamoros and Brownsville in Celedon’s, to a couple on a boat fishing trip out in the Gulf as imagined by Zertuche.

Alejandra Zertuche, Lazos de mi Ciudad (2021), painting on wood panels. 5 x 5 x 5 ft. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright Alejandra Zertuche.

Rube E. Garza, Lazos de mi Ciudad (2021), painting on wood panels. 5 x 5 x 5 ft. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright Rube E. Garza.

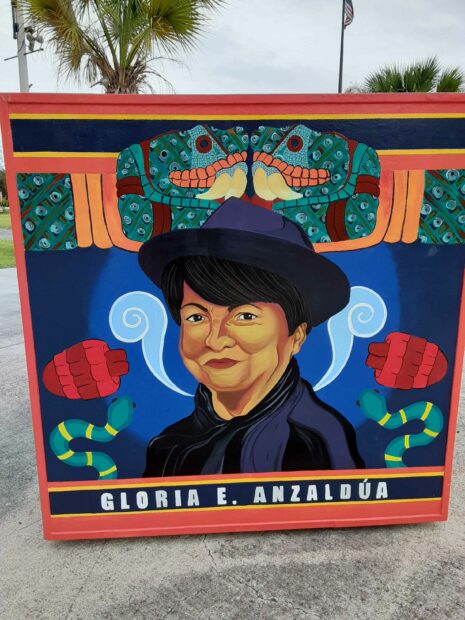

Another piece by Ruby E. Garza celebrates the work of Gloria Anzaldúa, a queer, feminist cultural theorist from Harlingen. Altogether, the works in this outdoor exhibition describe the lived experiences of women in the region. Perhaps these could be read as the community’s response to Smith’s reflective inquiry about the role of South Texas women in his mirrored folding screens.

Ray Smith: Pansy Pensamientos is on view at Brownsville Museum of Fine Art in Brownsville through January 28, 2022.

Thanks to Dr. Manuel C. Flores, the author of Cuentos Tejanos (Lime Press, 2021), for sharing with me his knowledge of early Texas history for this article.