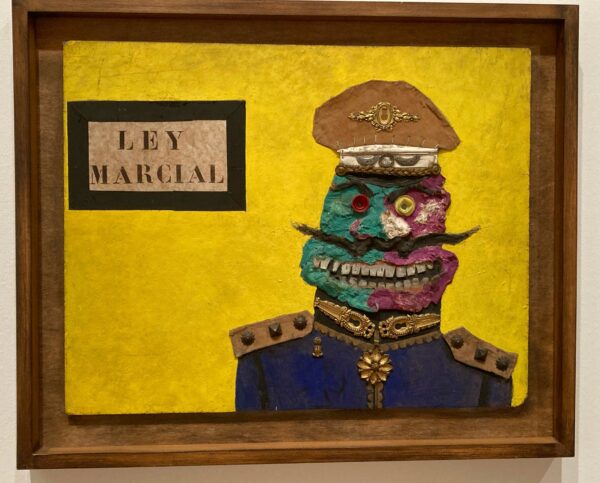

Antonio Berni, Ley marcial o le dictateur [Martial Law or The Dictator], 1964, Oil on particle board with cardboard, velvet, plaster, plastic, gilded escutcheons, tap shoe tips, nails, and staples

Portraits of military men are quite predictable. The stance, the pose, the soldierly medals pinned to their chests — the trappings of status are easy to recognize, and the unspoken gravitas of it all becomes part of the portrait’s implicit social text. “This,” such portrait tradition would seem to say, “was a really important man who did really important things.”

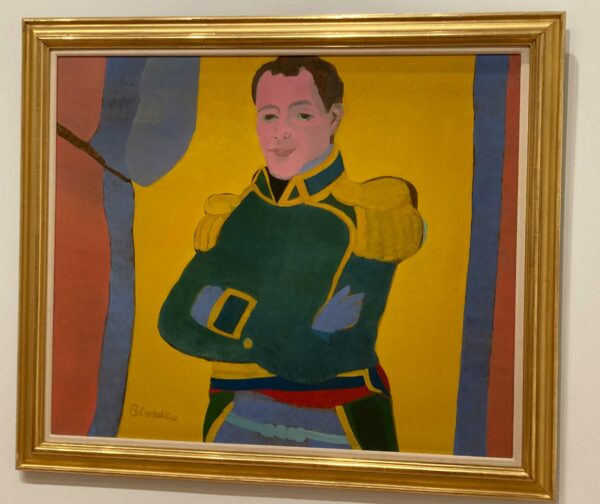

Colombian artist Beatriz González’s painting, Apuntes para la historia extensa, continuación [Notes for an Extensive History, Continuation], turns the expectations of such military portraiture on itself. Painted in 1968, almost a decade after Colombia’s ten-year civil war, Apuntes is a portrait of Simón Bolívar, the iconic nineteenth-century figure — a hero in Latin America’s fights for independence from the Spanish Empire. In Apuntes, González paints a contemporary Bolívar in a military uniform with garish, unflinching colors; he stands with crossed arms while the blue, red, and yellow stripes of Colombia’s flag run vertically around him.

Beatriz González, Apuntes para la historia extensa, continuación [Notes for an Extensive History, Continuation], 1968, Oil on canvas

Apuntes para la historia extensa, continuación is currently part of the Blanton Museum of Art’s ongoing Pop Crítico/Political Pop: Expressive Figuration in the Americas, 1960s-1980s exhibition — an exploration of politicized Pop art in the United States and Latin America. Indeed, the exhibition reminds audiences implicitly and explicitly that Pop art was much more than just Warhol’s soup cans and Marilyns; Pop was powerful, and used irony, satire, and even ridicule to explore difficult political positions. The show, overall, is a careful, nuanced exploration of Pop art’s power as a tool of social and political critique in the mid-to-late twentieth century.

In political philosophy, the “body politic” refers to the idea that a governing polity (a church, a state, a society, or an institution) can be understood — metaphorically — as a physical body. This working metaphor lets us talk about leaders as physical heads of state with other collective members, or citizens, forming the physical body. In Pop Crítico, the works on display show how artists turned toward symbolic figuration, known in Latin America as nueva figuración or neo-figuration, as part of their critiques and commentaries on their respective bodies politic. Works like Apuntes para la historia extensa, continuación show Pop art’s power to reinterpret and reimagine — González’s work is a twentieth-century reinterpretation of José María Espinosa’s classic portrait, Simón Bolívar (c. 1830), that would have been anywhere and everywhere in Columbia (and therefore easily recognizable) to González’s audiences.

Indeed, the body — allegorical, metaphoric, or literal — and its suggestion of being the body politic is at the very center of Pop Crítico. For example, George Segal’s Blue Woman in Black Chair (1981) is a life-size plaster cast of a blue woman lost in a moment of unguarded reverie. She is covered only by a deep blue blanket tucked around her shoulders and sides.

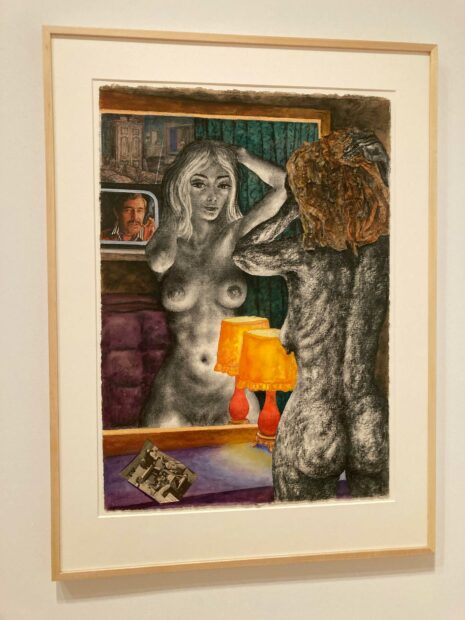

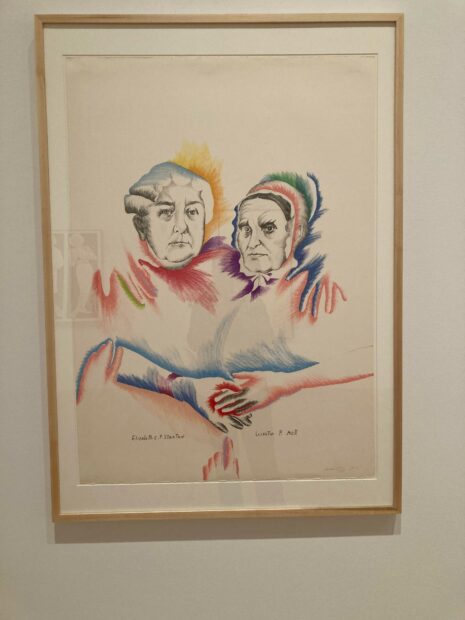

Antonio Berni’s 1976 drawing Circe (Enigma) shows a nude woman looking at herself in a mirror. The woman’s reflected body is joined by the gaze of a playboy voyeur who watches her as the audience watches him. Marisol Escobar’s lithograph of Elizabeth Cady Stanton (an early advocate in America’s women’s rights movement) and Lucretia Mott (an early feminist and abolitionist) suggests that the power to change the head (i.e. governing ideas) of a body politic system comes from the members of its body. (This theme is shared by Rubert García’s screenprint of Mother Jones.)

Antonio Berni, Circe [Enigma], 1976, Watercolor, charcoal or oilstick, and collaged magazine paper on paper

Marisol Escobar’s Pocahontas (1976), in particular, offers a pointedly sharp political commentary that coincided with America’s bicentennial celebrations. Escobar’s portrait of the Indigenous American woman Pocahontas (also known as Motoaks and later baptized as Rebecka) is based on a 1616 engraving by Dutch printmaker Simon van de Passe. In van de Passe’s original, Pocahontas is given Anglo-Saxon facial features and is clad in an elegant lace ruff and embroidered coat as part of her journey to England to appear in court as a “noble savage.” The original portrayal of Pocahontas falls neatly into America’s mythology surrounding its settlement. Escobar, on the other hand, “literally turns the portrait inside out,” Pop Crítico’s wall text explains. “Her Pocahontas has black skin, her dark hair cascading out of her hat…Pocahontas’s black skin may be a reference to the enslavement of Africans as well as Native Americans during the colonial period and the ongoing fight for civil rights even two hundred years after American Independence — and beyond.”

Marisol Escobar, Women’s Equality from Kent Bicentennial Portfolio: Spirit of Independence, 1975, Lithograph

In short, Pop Crítico’s works explore how artists challenged their respective body politics on issues of economic inequality, racism, anti-war sentiments, the then-nascent AIDS crisis, and state-sponsored torture under military dictatorships. Pop Crítico shows us that from the 1960s through the 1980s the members, citizens, exiles, and artists of the body politic — who all made up the governed body — used their art as a primary means of working to enact meaningful change on their environments.

Pop Crítico/Political Pop: Expressive Figuration in the Americas, 1960s-1980s is on view at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin through January 16, 2022.