Sci-fi films that take place in a dystopic or post-apocalyptic future usually include a scene depicting the grim options for entertainment and distraction: there’s the holographic girlfriend in Blade Runner 2049; some weird new drug in an aerosolized or otherwise vaguely cyberpunk form whose high seems wholly unappealing and nightmarish (Dredd, Looper, Minority Report); the hero clings to some faded, scratchy media remnant of an earlier, idyllic world — Denzel Washington listens to Al Green on an ipod in The Book of Eli, and in I Am Legend Will Smith tearfully watches Shrek over and over murmuring all the lines from memory.

Imagine a dystopic sci-film from 1995. Say it stars Jason Patric and Julia Ormond and is directed by Oliver Stone. Harold Pinter wrote the screenplay and Ryuichi Sakamoto did the score. It is a prestige picture, but laced with the druggy fever vision of Stone in the early to mid ’90s. It takes place 25 years in the future: a global pandemic rages; the virus can be deadly and when survived leaves the victim with an array of mysterious maladies. An ecological crisis continues unabated; there are near constant fires, hurricanes, and floods happening all over the world. Most nations drift politically rightward into ethno-nationalism and fascism. The president of the U.S. is a former reality star — a simulacrum of a flashy real estate broker who resembles a gigantic basted Chuckie doll and traffics in rote bigotry and authoritarianism, with a jack-booted police force and white militias at his beck and call. He loses an election to an old man prone to reveries about working as a lifeguard in the 1950s, but refuses to concede while firing all civilian leadership of the Pentagon in his own Saturday night massacre. The people of America are cowed and neurotic, addicted to their cassette-sized minicomputers they carry everywhere, which both surveil them and feed them a steady stream of nonsense, pornography, and conspiratorial rumors brayed as news.

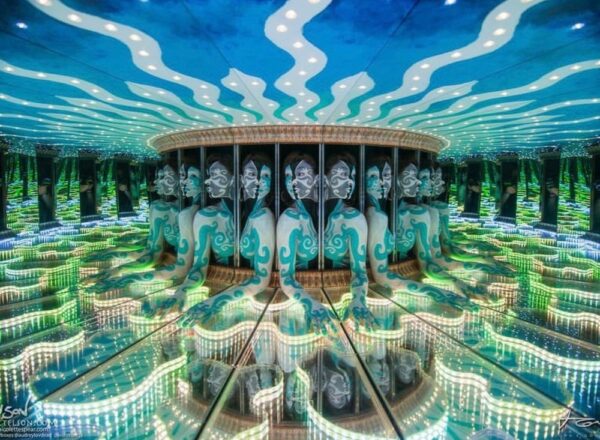

What is the first scene of this film? An interactive art exhibit: works made up of LED lights and thermal imaging; the patrons are all masked up, their hands in latex gloves; the air is misted continuously with antiseptic spray. A child approaches an interactive display and raises her hand to touch it before her mother pulls it away. “Don’t touch anything,” the mom says.

This was the bleak headspace I entered Hopscotch with. A new immersive exhibition space in downtown San Antonio, it boasts thousands of feet of galleries, a swanky bar, and a patio with a hipster fried-chicken food truck. In better times, Hopscotch would be buzzing with concerts and events, but now feels tenderly yet abrasively out of place, like a blissed-out burner at the funeral for a nun.

You may think from previous writing that I am predisposed to despise “immersive art,” but that is not the case. I don’t think I hate any art right now save for maybe especially cringey and banal text art high on its own delusion of profundity. I am instead puzzled by immersive art. Puzzled at how, despite cutting-edge technology, most of it seems nearly identical: there is always a TRON-like room of latticed LEDs; some piece that responds to thermal heat of the body; a glowing cave or igloo-like structure that has some environmental message (in Hopscotch, this is a glacial canyon of white plastic bags representing the number of bags Texas throws away every three minutes); a nod to graffiti and street art culture; and so on. Also puzzled about why the “immersive” art of Walter De Maria, Robert Smithson, and Donald Judd feels like art, while most contemporary “immersive art” feels like… something else. I don’t think it’s simply that the minimalist installation artworks are pilgrimages to distant, rural nowheres, ensconced in the whispered austerity of their solemn and fantastically expensive gift shops and general monastical penitence, while contemporary immersive spaces are often sponsored by corporations that make those Hobbit-toe shoes, or a bladder-like contraption that allows you to hydrate while downhill mountain biking.

The first possible answer lies in the conundrum of technology. New immersive art splashes around in the future — using artificial intelligence and virtual reality, and probably soon enough nanotechnology and transhumanism. So why doesn’t it blow our minds? Imagine if Francis Bacon mastered virtual reality, as he had painting, to communicate his vision of the stark and desperate agony of existence? But technology is difficult to master. Think of what Bergman said of Tarkovsky: “Tarkovsky for me is the greatest [of us all], the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream.” The apotheosis of Tarkovsky’s craft — the realization of his “poetic cinema” — came with 1965’s Andrei Rublev (in my mind the greatest film ever made) nearly 70 years after the Lumiere Brothers’ Journey on a Train. New technologies need time to reach a prime.

But there’s also a question as to whether these new technologies can even be tamed. Traditionally, the actual use of technology — a film camera, video, animation, etc. — is akin to a winnowing fan or a sail, used to separate the wheat from the chaff, or catch the wind of one’s vision. This era of tech is perhaps too complex, too self-aware, its geometric algorithms unfurling like endless curtains. Perhaps such technology cannot become an appendage, and instead is a sullen teenage genie in mocking disbelief that you don’t know what you want.

Another explanation as to why I find myself underwhelmed, or at best bemused (as opposed to bowled over), by the newer kind of immersive art is that the situational context it is almost always meant to convey is diversionary, glitzy fun. It is hard to feel solastalgia — the dread and anxiety from witnessing environmental collapse — in a buzzy, lighthearted space with cocktails and a deep house DJ. This is a conundrum that extends beyond immersive art. Art can be many things, yes, including instructive, righteous, engaged in the social and environmental, and yet not too much of an ordeal. Art can confront racism, but apparently the lacerating Klan paintings of Philip Guston are far too much for museum goers. So, art becomes a Flintstone vitamin — cloyingly sweet, goes down easy, and the label says it’s good for you. But is it really?

The greatest immersive art I’ve ever experienced came last fall, during the halcyon days when the Austin Film Society was open and regularly screening global cinema masterpieces. I attended a rare screening of Bela Tarr’s eight-and-a-half-hour leviathan Sátántangó. Relentlessly (almost hilariously) bleak, glacially paced, and shot in stark black and white, Sátántangó tests the viewer — physically and emotionally. Some might say Tarr was punishing his viewers, but I think the opposite is true. He respects the viewers and believes in them, believes that they can handle this journey up the mountain.

These are dark times, and more flirtatious with the apocalypse than any spikes during the Cold War. Similarly, the art we deserve — the art we need — is the unsentimental, solemn, unfun gravitas of Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice and Bergman’s Winter Light. I end with an exhortation to the world of immersive art: take me to hell. After all, we already live there.

3 comments

Here Here Neil!!! Nailed it again! Always enjoy reading your mind. Peace.

Thank you Neil, thoughtful and provoking words.

I think that all art is a trick and/or a lie, but when it’s really great it’s a trick/lie that points us to greater experiences with truth than we can often access through reality. The problem with this new brand of “interactive” art is that it often points to nothing greater than it’s own techno-novelty and our own solipsistic experience with it (often mediated through other layers of technology like our camera phones and social media)–and so unfortunately there seems very little behind the curtain to see (unless corporate sponsorship can be considered content, and maybe these days that is a form of the truly grotesque).

Tarkovsky’s search for a pure cinema was not in itself what makes Solaris, Stalker, The Mirror, etc. so great, it was his ability to transport us so completely to the rag and bone shop of the heart through that cinema–his mastery of the technology and the poetry of it was the vehicle used to get us there, a beautiful, novel, and essential vehicle to ride in for sure, but certainly not the only point of the ride. These new interactive complexes seem to me like driving beautiful cars around the sales lot, in circles, over and over, as if that was point–and perhaps if the end goal is simply photos for a social media feed then maybe there is no reason to actually go anywhere, as that an image of yourself in front of the automobile is enough to convince followers of what social media demands we convince them of–something I’m not sure I completely understand.

I totally agree that it is the very safeness of these interactive complexes that renders them nearly mute as far as capturing any real human experience is concerned. Perhaps large portions of the public wouldn’t line up for a Bacon induced VR nightmare, but the barely PG-13 worlds these complexes exhibit do little, as Neil eloquently put it, to help us grapple with the “hell” we currently inhabit. Maybe that’s OK, maybe escapism is the point, but escapism right now feels extremely dangerous to our future as a species–and if/when that is what we begin to expect out of art then perhaps we will loose our grip on what great art has always given us the chance to grasp through its beautiful lie.

I also don’t hate these interactive complexes, and maybe whatever gets people out to see something other than what’s streaming on Netflix can’t be bad–maybe these complexes will become entry drugs for better, harder art. But maybe that’s wishful thinking, they may just as likely be robbing people of the ability and attention span to appreciate art that truly “respects” its audience. I don’t pretend to know the answer to that, but I am skeptical of any art that is so easily commodified, so obviously concerned with its own novelty and spectacle, and so easily consumed like junk food eaten out of compulsion not hunger for substance.

Thank you for this article which helped me articulate and focus a rumbling of thoughts I’ve tried to put a finger on for a few years!

Thanks for reading and for this interesting and intelligent response!