Artpace San Antonio’s Spring Artists in Residence exhibitions opened on March 19th, after the shelter in place order, thus very few people have seen the shows in person. (This week Artpace has reopened to the public by appointment.) As is the case with most Artpace residency shows, the installation element is foregrounded in the work. The three shows use the tactility, dimension, and heft of their objects for narrative immersion. Each of the artists has a tale to tell and their exhibits are winding roads of sorts.

Milagros de la Torre is a Peruvian-born artist working in New York whose work combines sculpture, video, photography, and installation. In Systems and Constellations she explores the mysteries of the human face. De la Torre has the memory condition prosopagnosia, or face blindness, which makes remembering a human face very difficult, and so Systems and Constellations ponders the measure of a face, and the tools used throughout time to map it. In the video Intervals, methods of facial measurement throughout history (calipers, etc.) flicker across the screen. The dark legacy of facial recognition in the service of racism and oppression is a spectre that haunts the show. De la Torre grew up during a period of great social and political upheaval in Peru and South America — a time of U.S.-backed juntas and forced disappearances (the great Costa Gravas film Missing comes to mind). This harsh charge vibrates throughout the show, where being “spotted,” recognized, etc., could mean imprisonment or death.

Erased, Deleted, Omitted, a translucent 3D sculpture of a human head with a pixelated visage, explores the topography of the face and the conundrum of depicting and transmitting it. The pixels form a latticework that resembles the Giant’s Causeway in Ireland, and are similarly blank and inscrutable. The effect is to highlight the contradiction that the components of perception are themselves fungible and generic. What then is a unique face?

In a series of portraits, facial patterning overlays the faces of the subjects. In Recollection #1, a convex mirror (often used for surveillance) is overlaid with constellations of significant dates in de la Torre’s life, as well as other milestones (like Linda Pace’s date of birth). The effect of these works creates another fertile conundrum: Is a face a record of one’s life, or a map? Do the patterns of your face tell a story, or are they themselves the story?

Daniel Ramos’ The Land of Illustrious Men takes an earlier art book he’s created and transforms it into an affecting, immersive personal epic. The shows chronicles Ramos’ family journey — his father paying a coyote to take him across the border, growing up in inner-city Chicago, and spending summers with his grandmother in Lampazos De Naranjo, a small town in Nuevo León, Mexico, to avoid falling in with gangs. The show forms an elegiac, holographic memory assembled from family photos, large-scale art photos, mementos, notes, and at the centerpiece, two powerful sculptural pieces — the Ramos family van that made the trips from Chicago, and Ropero Al Viento (Wardrobe in the Wind), a wardrobe filled with mementos beneath rusting mattress springs with rosaries and other talismans hanging from it.

The Land of Illustrious Men is an example of the Martin Scorcese adage “The most personal is the most creative” in action. By plumbing the depths of his life, its memories and objects and the invisible energy radiating between them, Ramos creates a theater of universal saudade, the Portuguese word for the intermingling of melancholy and nostalgia. Ramos’ pieces and their memories wash over you, and you drift into the current of your own life and all that came off and was lost in the waves.

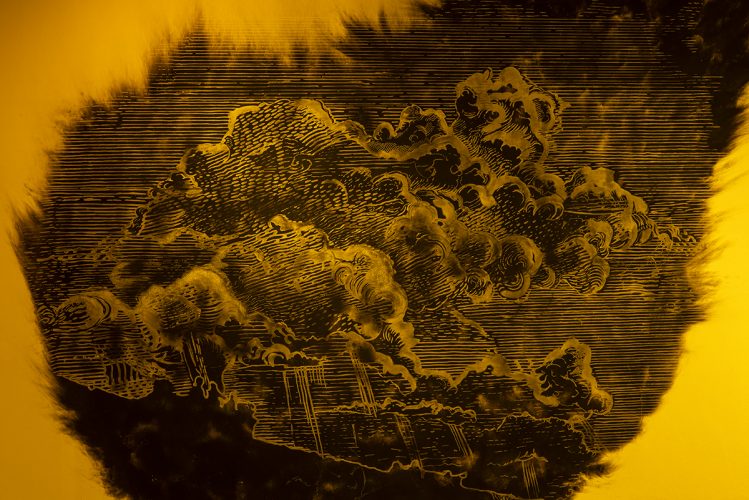

Colombian artist Carlos Castro Arias’ literally incendiary I Came To Set The World On Fire, And I Wish It Were Already Kindled is a hallucinogenic, terrifying and exhilarating baptism of flames. Castro’s show works with simple elemental symbols and images — churches, fire, ashes, and flames. A video of churches of different sizes narrated by the unctuous lilt of mega-pastor Joel Osteen takes on an ominous and sinister heft, surrounded by the other works that involve flames, ashes, burn marks, and shadowed figures. Two pieces involve propane tanks and lit flames, a burning church and a shadowed figure in a Rodin’s Thinker, like pose with a ring of fire around the figure’s mouth. Other wall pieces made from soot and ashes depict burning churches, flames, and ominous clouds.

These are familiar themes — the fire of love, faith, and hate, the fire of annihilation and rebirth, the fire of transference, the legacy of churches being burned, the religiosity of the south. Castro wisely does not particularly analyze these subjects, but creates a churning furnace of sensation. The feeling evoked by Castro is reminiscent of the brilliant Belarusian anti-war classic Come and See, a sort of unflinching spiritual horror. Like the title of the burning man (The Witness), Castro creates a frenzied vision and bears witness.

So too, do the other artists in this exhibition. The great poet Rabindranath Tagore described the Taj Mahal as “a teardrop on the cheek of eternity.” This exhibition attempts to look into the eyes.

Through Aug. 23, 2020 at Artpace San Antonio. Now open by appointment.