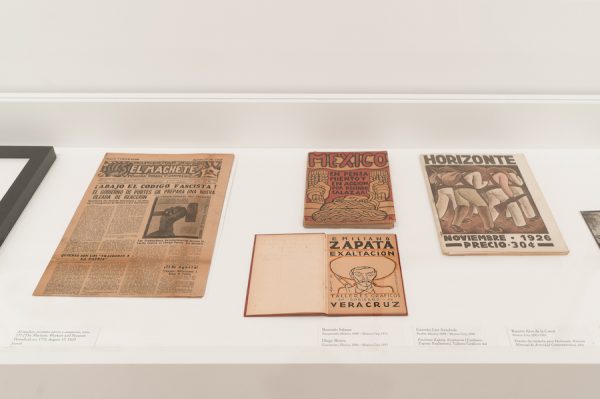

View of The Avant-garde Networks of Amauta: Argentina, Mexico, and Peru in the 1920s at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin

The 1920s were a busy time for Latin American writers, artists, philosophers, and intellectuals.

Many, like Peruvian political philosopher and journalist José Carlos Mariátegui, traveled through Europe, connecting their own thinking with the then-burgeoning movements of Dadaism, Futurism, and Surrealism. Across Europe and Eurasia, Marxism offered a theory to make sense of social inequality, class struggle, and a framework for revolution. These early twentieth-century networks offered the world new literature, art, and political theory. When writers like Mariátegui returned from their often self- or government-imposed exile, they took these avant-garde networks and made them unique, powerful, and specific to Latin America.

View of The Avant-garde Networks of Amauta: Argentina, Mexico, and Peru in the 1920s at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin

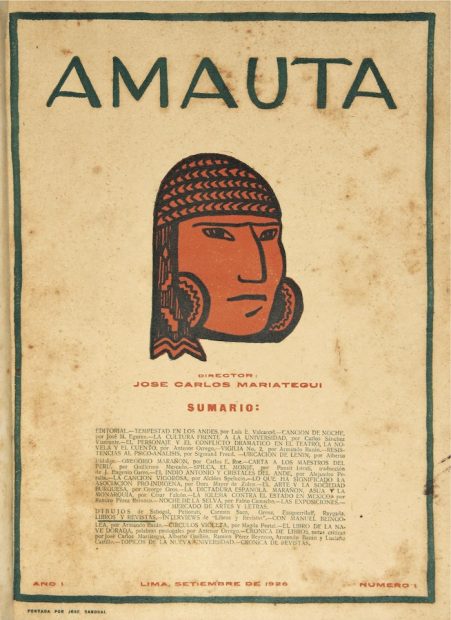

These Latin American voices became the epicenters for powerful, far-reaching intellectual projects in the mid- to late-1920s, like the Peruvian magazine Amauta. Amauta, in turn, became an incredibly complex network of Latin American intelligentsia, publishing works by Jorge Luis Borges, André Breton, Sigmund Freud, George Grosz, Pablo Neruda, Diego Rivera, Xul Solar, and Miguel de Unamuno, to name a few, as well as the plethora of artists who contributed to the magazine. Amauta’s emphasis was Latin America, but this was a Latin American perspective that offered an alternative narrative to traditional colonial history thanks to the publication’s emphasis the modernist intellectual movements, creating a physical, ephemeral, circulating text, and, in particular, Amauta’s commitment to Indigenism.

View of The Avant-garde Networks of Amauta: Argentina, Mexico, and Peru in the 1920s at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin

Amauta, año I, núm. 1 [vol. 1, no. 1], September 1926, magazine, 13 5/16 x 9 5/8 in., Archivo José Carlos Mariátegui, Lima.

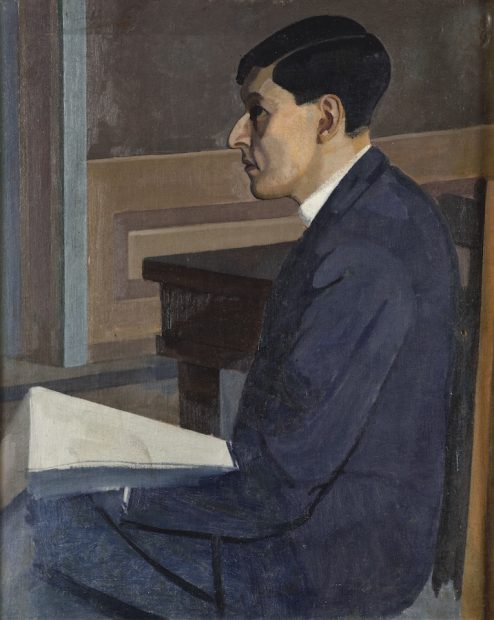

Emilio Pettoruti, José Carlos Mariátegui, 1921, oil on canvas, 24 13/16 x 20 1/4 in., Museo de Arte de Lima; © D.R. Fundacion Pettoruti, www.pettoruti.com

Almost a century later, history has confirmed that Amauta made a lasting and global impression during its four-year run. (Publication was cut short by Mariátegui’s death at the age of 35.) More to the point, however, the exhibition The Avant-Garde Networks of Amauta: Argentina, Mexico, and Peru in the 1920s — currently at UT’s Blanton Museum of Art in Austin*— reminds audiences that the printed editions of Amauta might be the stuff of historical archives, but the publication’s ideas, discourse, art, and politics are just as vivacious and incisive as they were at the beginning of the twentieth century.

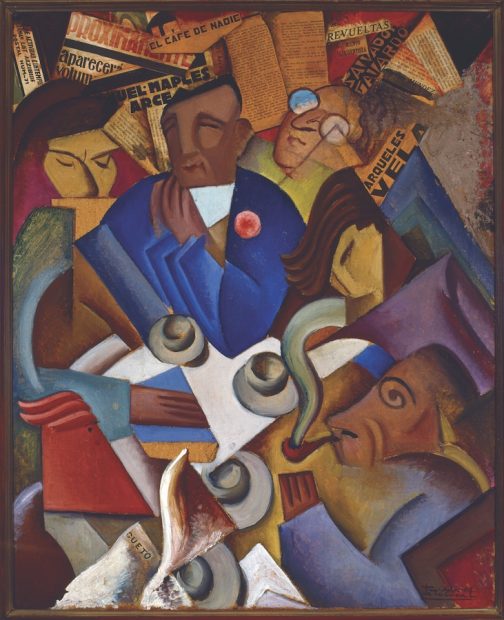

Ramón Alva de la Canal, El Café de Nadie[Nobody’s Café], circa 1930, oil andcollage on canvas, 30 11/16 x 25 3/16 in., Museo Nacional de Arte/ INBAL, MexicoCity; © D.R. Museo Nacional de Arte / Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura, 2017. Courtesy of Jorge Ramón Alva Hernández.

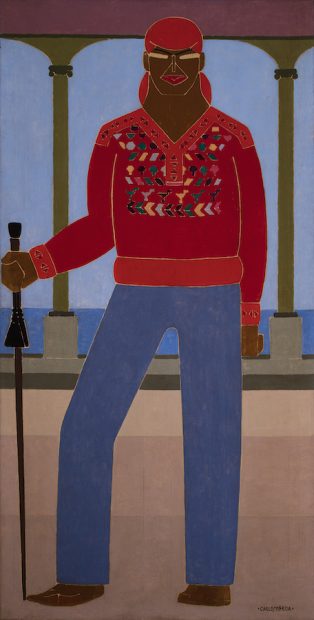

Carlos Mérida, Alcalde de Almolonga[Mayor of Almolonga], 1919, oil on canvas, 70 1/16 x 35 1/16 in., Colección Andrés Blaisten, Mexico City; © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOMAAP, Mexico City Photo: courtesy of Colección Andrés Blaisten; photographer: Francisco Kochen

The subtle, profound theme that underscores The Avant-Garde Networks of Amauta, however, is the social life of print and how printed works like Amauta circulated vanguard ideas within Latin America as well as to a larger, global audience.

View ofThe Avant-garde Networks of Amauta: Argentina, Mexico, and Peru in the 1920s at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin

View ofThe Avant-garde Networks of Amauta: Argentina, Mexico, and Peru in the 1920s at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin

Print is a social phenomenon, and throughout its history, it has connected people with ideas and with each other at a scale that was impossible without it. However, mass-produced print — like pamphlets, handbills, and periodicals– is disposable and has been throughout its history. These medias are meant to be copied en masse and circulated within social networks — but not necessarily to be saved, collected, and curated. Stepping into The Avant-Garde Networks of Amauta feels a bit like seeing the life cycle of mass-produced print suspended; someone, somewhere did save the printed materials, and those texts are available for this exhibition. Printed text that was once assumed to be ephemeral has achieved a bit of immortality.

View ofThe Avant-garde Networks of Amauta: Argentina, Mexico, and Peru in the 1920s at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin

In essence, then, Amauta is being re-circulated through the exhibition’s visitors coming, taking photos, and even posting them to social media. The journal is being disseminated again as visitors learn about its left-wing intellectuals and the network that Mariátegui and his cohort built. It’s hard to imagine a more fitting afterlife — history is still confirming how audiences read and experience Amauta, nearly a century after its original publication.

****

‘The Avant-Garde Networks of Amauta: Argentina, Mexico, and Peru in the 1920s’ at the Blanton Museum of Art, Austin. Feb. 16 through Aug. 30, 2020. *Please note the Blanton Museum of Art is temporarily closed and will reopen as soon as the situation allows.

Curated by Beverly Adams, Former Curator of Latin American Art, Blanton Museum of Art, now Estrellita Broadsky Curator of Latin American Art, The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), and Natalia Majluf, Former Director and Chief Curator, Museo de Arte de Lima, Peru.

3 comments

Great review! What a fascinating show.

Sounds fascinating. Is there a catalog of the show?

Yes, the catalogue is excellent!