Joris Laarman, produced by Joris Laarman Lab, Bone Rocker, from the collection Bone Furniture, 2008, black marble and resin, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Mary Kathryn Lynch Kurtz Charitable Lead Trust. © Joris Laarman

The infinite possibilities of digital tools for creative pursuits is ultimately a referendum on human creativity. Most people need rules and limitations. This is why CGI in movies, despite budgets in the hundreds of millions, is often repetitive and turgid, why much of music made with computers sounds tiresomely uniform, and why almost all restaurant websites are infuriatingly terrible. But, we are beginning to reach a stage where artists born in a “millennial” generation have a seemingly preternatural fluency with digital tools, and one feels a bolt of excitement that a wave is coming of things truly wondrous and unseen.

In 2004, Joris Laarman, a young Dutch designer, founded the Joris Laarman Lab with his partner Anita Star. The lab is the definition of bleeding edge, using highly advanced digital fabrication methods and robotics, but unlike some uses of such sophisticated technology which are mainly a demonstration of their power or novel abilities, Laarman uses his technology as a true collaborator — a dancing partner, if you will — for his dreams.

Joris Laarman, produced by Joris Laarman Lab, Dragon Bench, designed 2014, made 2015, stainless steel, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund. © Joris Laarman

Much of the work in the show of his work at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston is furniture that is simultaneously highly functional (in that the pieces look extremely comfortable) and deeply whimsical and expansive. The pieces contort, bend, bow, and expand in almost improvisational ways, as if they were kinetic and in flux, jumping from one dimension to the next. Dragon Bench, a webbed, stainless steel structure, resembles shapes in quantum physics, black holes, and wave theory. Titling the piece Dragon Bench connects myth to science, through the quantum power of imagination. Imagine a shape: It’s real. Imagine a dragon: It’s real.

Joris Laarman, produced by Joris Laarman Lab, Branch Bookshelf, 2010, bronze, the Groninger Museum, the Netherlands. © Joris Laarman

Several of the pieces have echoes to design aesthetics of the past, and use the power of the lab to extend these aesthetics in a way that feels organic and magical, like vines growing over a castle overnight. Branch Bookshelf resembles a classic art deco work if it were to come alive, gain sentience, and grow on its own.

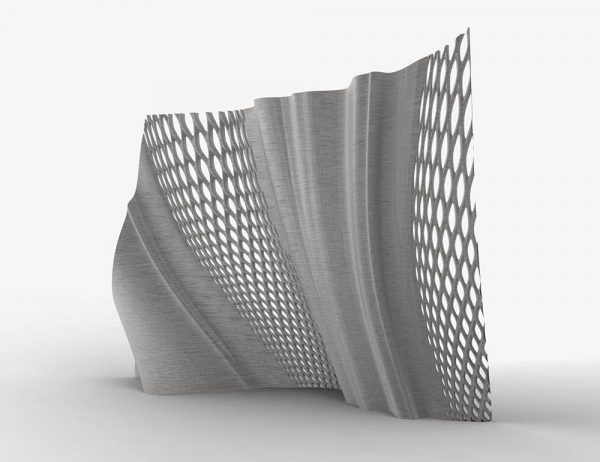

Joris Laarman, produced by Joris Laarman Lab, Gradient Screen, 2017, stainless steel, courtesy of Joris Laarman Lab. © Joris Laarman

Some of the works are essentially sculptural installations. Gradient Screen appears as if an otherwise unexceptional metal screen from, say, an office park, bends and contorts itself into something playful and new. Part of Laarman’s technique and practice is rooted in unleashing familiar shapes — chairs, couches, shelves — allowing them to evolve or devolve with a spontaneous flair. Even though obviously the effort in creating these works in enormous, the result is cathartic.

A humorous centerpiece of the show is rococo-style tables designed using the pixilation techniques from Nintendo game consoles. Laarman places figures of the Mario (from the Super Mario Bros franchise) and his evolution over various incarnations above the tables. Placing the intricate tables, referencing a time of gilded aristocracy, next to video game characters is a witty connection that contextualizes a stuffy history of design, and elevates a nascent digital aesthetic. These are the same, Laarman seems to say. Divorced from history, they are ephemeral pursuits of aesthetic delight — nothing more, nothing less.

In a series of curving, twisting chairs, Laarman displays the working print of the chair on the wall, before it was contorted like a snake into a single elegant object. This show and Laarman’s methods and works are in themselves a heuristic for perception. Look at anything, really look, and let it come alive and breathe on its own.

Through September 16, 2018 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston