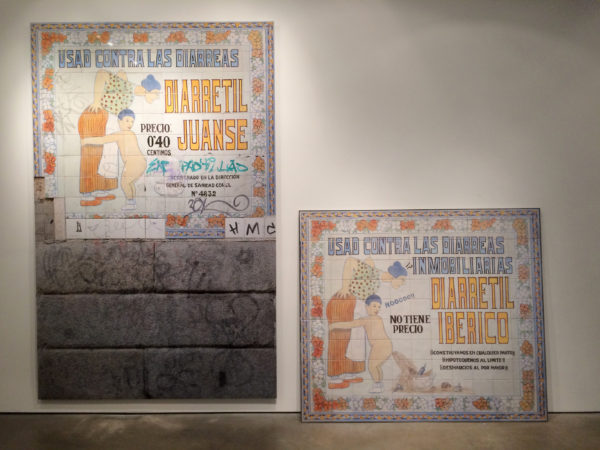

I don’t want to call them sculptures but they’re asking for it, leaning like that. You put anything on the floor and lean it and it just becomes a sculpture. Was it just too heavy to hang or is there some reason for its casualness? This is like a painting’s version of contrapposto. Not with a stick up its ass up on the wall, a bit more casual like you could pick it up and take it home with you and lean it there, too. They aren’t mosaics either, but they’re paintings on tile. I don’t know if there’s a shorter name for that. “Facades” is what they’re called or ‘fachada’ in Spain where they live, on the outside of a building, the Farmacia Juanse, a hundred-something year-old pharmacy in Madrid. Now restored and converted into a café (fucking hipsters).

On every wall at guerrero-project’s fifth show in their newly opened Houston space, these façades sit next to their photographic twins. As a sculptor, I always first try to understand how something is physically made. This includes the order of operations, the order of the layers. The leaning façades, cleaner and unmarked by graffiti, seem to come first. This duplicity of images is disorienting until you realize they are both photographs—just differently edited and printed. The hung photographs on the left are life-size representations of the Juanse pharmacy street corner in Madrid—these are the façades painted in 1924 by artist Enrique Guijo—and the right leaning photograph is an updated (corresponding) pastiche by artist Carlos Garaicoa.

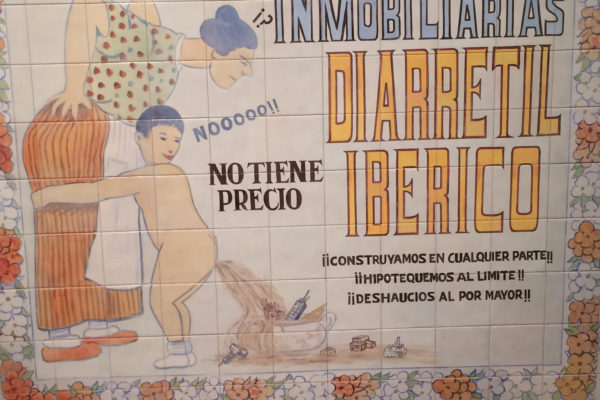

Now spot the five differences in two pictures. They used to have that game in the backs of junky magazines I’d thumb through waiting in line at Walmart. (Maybe they still do, but I shop at Kroger now and the lines are shorter). These images feel like you’re playing that game, swinging back and forth to find them all. In this one the boy has a graffiti erection. In that one he’s got projectile diarrhea. Why does his excrement contain intact buildings? Shouldn’t those, if they had been through his digestive system, be all chewed up? Maybe he’s shitting on the buildings, not shitting them out. Either way, in Garaicoa’s version, there’s the addition of buildings swimming in a surge of poo. The artist’s additions are cruder than the street vandal’s. The updated ad text translates as ‘For use against real estate diarrhea.’

‘Let’s build anywhere!! Mortgage to the limit!! Evictions wholesale!!’

So now we’re getting political. The unemployment rate in Spain (in 2014, when this piece was made) was 24.4%, one of the highest in Europe, which has led to widespread evictions. Ours is just under 5%, to put that into perspective. The overt political statements in Diarretil lead you to expect more of the same from the other façades, and it’s frustrating for me when they veer off that track. Despite the visual consistency of this show and production, the ideas and tone are wildly inconsistent.

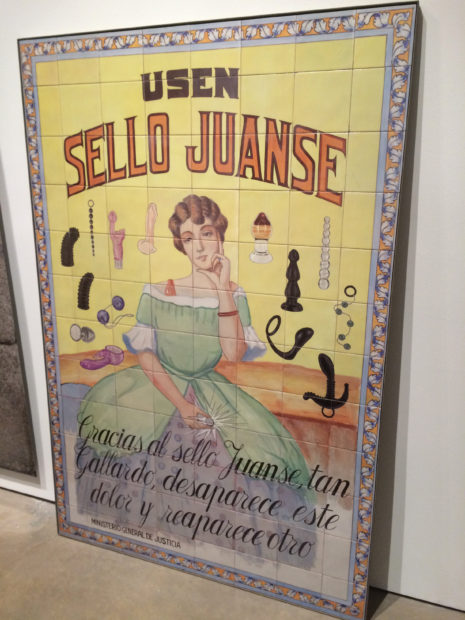

The hovering sex toys and woman’s hand placement in Cerámicas porno-indignadas (Un Consuelo eficiente) suggest that she is contemplating what to buy, her glowing coin representative of consumer choice. I’m either aware of or can guess at the function of all of these toys. Based on their shape, I’d say three are intended for women and two are intended for men; the rest could go either way. The text at the bottom reads Thanks to Juanse seal, so gallant, this pain disappears, and another reappears. None of these toys are intended to inflict pain, so I’m at a loss for what pain is reappearing. It’s a little dicey that the artist, a guy, has inserted sex toys into the woman’s consciousness. I’m reminded of a recent screening in Houston of the early-2000s Mel Gibson flick What Women Want.

The plain rendering of these objects within the style and frame of a 1920s advertisement is intriguing on its own, but the text’s ambiguity diffuses whatever statement this work could’ve made.

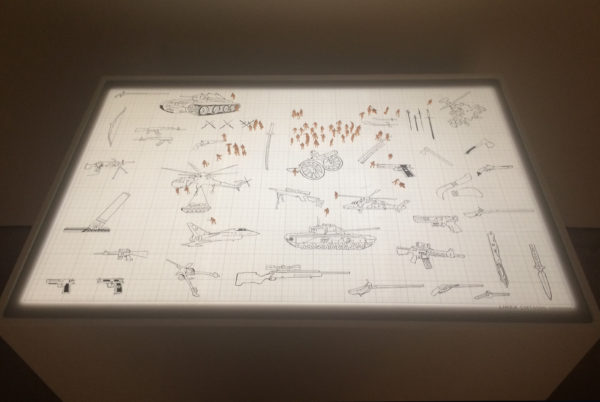

A small swarm of people stand on the surface of Visitando un lugar común (Visiting a common place), with the figures all cast in the same fleshy plastic. This microcosm of people affixed to the glowing surface diagram of various weapons: it feels like the board game Risk—tiny armies conquering enemy territories. But they’re not army men, they’re all unique civilians. The shoveler, the pointer, the walker, the wheel-barrow pusher, etc. Not that they’re achieving anything, but this setup makes you feel like you’re playing a game too, like they’re all pawns you could move around. The illustrated range of weapons feels representative of a human history of war. The title ‘visiting a common place’ paired with these war machines creates a funny contradiction—we don’t get along, but at least we all have that in common.

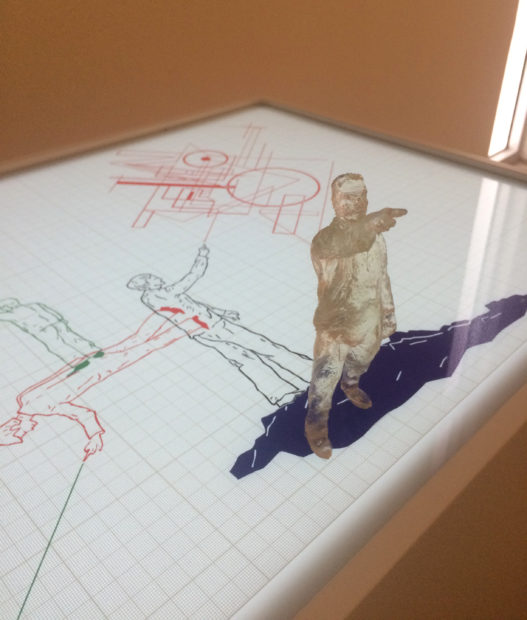

Who, me? I turn around to see if there’s anything up at the ceiling where the pointer is pointing. No. It’s me. The transparency of the cast makes it difficult to tell if this man is someone specific. He looks just as generic on the lightbox side views, with the addition of a line from his hand (seemingly holding the worlds dopest laser pointer). I can think of a string of monuments of men pointing like this. Dictators and conquerers, important men who know what they’re doing and how to lead and exactly what everyone needs. I see men like this falling, monuments to their existence dragged off.

Shrunken down, pointing up at me, his gesture isn’t one of power and expansion; it’s accusatory. A finger of blame. Accusing me of something. No, sir. I did not take your laser pointer.

Through May 27 at guerrero-projects.