I’m not feeling Angel Otero’s paintings. In fact, I think they’re pretty bad. But Angel Otero: Everything and Nothing, at the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, the artist’s first ten-year survey exhibition, is rich with teachable contemporary art-world moments.

Otero is an art star of the moment. When he was 24 he quit his job selling insurance and moved to Chicago to attend the Art Institute. In her Houston Chronicle profile of Otero, Molly Glentzer writes that “growing up in Puerto Rico, Otero was exposed to Old Masters and Modernists but knew very little about contemporary art—the installation and digital work so prevalent now.” I don’t know how much that has to do with growing up in Puerto Rico. I didn’t know what any of that shit was either until I went to art school.

Otero graduated in 2009 and four years later, in 2013, the then-32 year-old painter was reported by Blouin ArtInfo to have sold out Lehmann Maupin’s entire Art Basel booth. Selling for between $30,000 and $45,000 each, “Otero’s experiments in painting” as the CAMH’s wall text explains, “push[ed] the field into new territory.”

Unaware that “many people think painting is dead,” Otero was a quick study. After a few years he began cranking out big, lumbering, undead abstract paintings that spin their wheels over the grave of the New York School and hinge on the notion that because painting hasn’t yet saved the world from war and poverty, it must continually justify its existence by haunting the corpse of 20th-century abstraction.

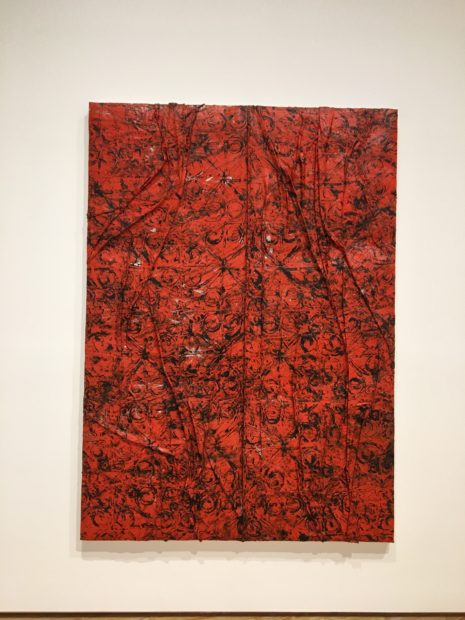

Otero’s “skin paintings” are like Houston hometown antihero Mark Flood’s “lace paintings.” Both rely on a rote, repeatable formal gimmick that yields predictable but just-slightly-varied-enough results. Flood monoprints lace onto his canvases. Otero glues half-dried crumpled oil paint skins scraped off Plexiglass onto stretcher frames. These two approaches exemplify the basic kit for making the zombie abstraction everyone’s been complaining about for a decade. The result are handsome paintings that exude the smell of oil paint for years and look great over a black leather couch behind a glass table covered in blow.

It’s not that making this stuff is easy, exactly. Otero probably works his ass off. In November 2015, Lehmann Maupin mounted New Paintings, an exhibition of his large-scale skin paintings. Six months later, Otero produced a whole new batch of work for the gallery’s Hong Kong location. After I make a show it takes me six months to remember my name. Whatever you may say about the work itself, Otero is hustling the art game for all it’s worth.

This is the market side and we all more or less know how it works. But we’d miss out on the greatest irony if I didn’t mention that the market drive for benign, disposable painting that fuels this hustle is paradoxically supported by the mopey theoretical Hal Foster wing of the art world that is firmly ensconced in the prestigious universities that, by and large, produce these artists. A hilarious parallel has grown up between the avant-garde’s relentless quest for the novel and the market’s relentless desire for the new.

The faculty at elite art schools, like Chicago, who feed the market with this steady supply of cutting-edge factory workers, aren’t comprised of free-market-Hilton Kramer-conservatives. There might be a few buried in the Medieval Studies department, but the studio and theory professors training these Hunger Games contestants are mostly Marxist deconstructionists filling nubile young minds, semester after semester, with the bitter remains of their failed utopian ideologies.

Otero’s Hong Kong show with Lehmann Maupin was curated by University College London’s Briony Fer, a British art historian and Foster compatriot, whose lectures usually revolve around how she can resurrect, in an appropriately ambiguous manner, the ghost of Malevich’s revolutionary abstraction in order to rescue the art world from itself. Star curator Okwui Enwezor announced that Marx’s Das Kapital was “our Bible” and sat at the heart of his recent iteration of the Venice Bienniale. The disingenuity is sorta breathtaking.

Originally invested in more autobiographical, representational material, Otero tells a story in which a studio visitor said, “I can give a shit about your grandmother.” That sounds like a dealer to me. But the curatorial version of the question might go something like this: “Your grandmother isn’t really the point. You and your grandma are mere fragments of the larger, Absolute Will striving to achieve itself.” Or something like that. Whoever said it, it did the trick. With the exception of a few early still lives, Otero’s paintings have, since graduate school, been built on a technique that buries his personal narrative under a goopy mountain of expensive high-pigment oil paint. More recent paintings hide that narrative under a silicone transfer process.

But we’re all adults here. It’s a consensual agreement. Otero, and the Joe Bradleys and Dan Colens a decade before him, know how this feedback loop works. What artist would turn down the opportunity to open an art factory and make hundreds of thousands, maybe even millions, of dollars? These star painters may not be good artists but they’re smart. They’re savvy enough to know what the high-dollar end of the art world wants from them. Running a big art studio in Bushwick where you can get high all day is a better gig than construction or sex work.

Do I think these artists are stupid or being taken advantage of? Well, yes and no. I do think most of them have taken avant-garde Duchampianism, taught by the aforementioned Marxists, too seriously. The idea of the avant-garde, or progress in art, is built on the belief that art is going somewhere. As far as I’m concerned painting has been totally destroyed. Lucio Fontana’s tasteful rape of the two-dimensional surface was all I needed to know that the zero-sum in painting had been reached. I just don’t buy this resurrection game anymore. Do we need to keep circling this drain? Maybe it’s time to change the subject.

I know, I’m a grinch. Well, the grinch can’t help it. He is what he is. One of my favorite grinches is Arthur Schopenhauer. He thought the essence of human nature was pretty much evil. He called it Will, and it was the mindless, non-rational instinctive urge at the bottom not just of people but of the whole universe. I’d like to see fewer shows about what I see as an absolutely barren and sometimes totally dishonest utopian art narrative and more about the irrational, fucked-up, war-mongering world that, as far as I can tell, we’re living in right now. Merry Xmas. See you next week.

Through March 19, 2017 at the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston.

3 comments

Smart, insightful and yes, a touch grinchy, I must admit I HAVE TO stop at CAMH and see Otero’s work after reading Michael’s review/takedown. I just can’t resist. Merry Christmas.

one of my dreams is that this dude will write a bad review of one of my art things, seriously, I love this stuff and I wish more of it was in the art world (honest writing), MB, we love your writing, keep it up you cranky so-and-so and thank you 🙂

Another good one , Mr. Grinch. Exactly what I thought (but better written) after I read review in Sunday’s Chronicle. Happy Holidays.