Still from The Warriors (1979)

Though I’d gathered scattered, vague notions of its history from films, photos, and writings, I must admit that until recently I really just thought of Coney Island as a funky void—a place of long-orphaned urban ruin. My concept of Coney Island was probably derived mostly from its depiction as an empty, end-of-the-line gang turf in the movie The Warriors (1979), and perhaps supported by the presence of its Cyclone rollercoaster in The Wiz (1978) as the abandoned junk heap under which an animatronic carnival performer had been left to rust “after the park went el foldo.” But I started thinking more about the significant history of Coney Island’s social-commercial-technological experiment last spring while watching the first season of Mr. Robot. The headquarters of that show’s central anti-corporate, technological revolt is ingeniously hidden in plain sight in an abandoned Coney Island game arcade, and some important scenes with its main character and his mysterious mentor are set in the Wonder Wheel and on the boardwalk. While it doesn’t overstate an analogy, Mr. Robot is the kind of show that nudges viewers to connect dots and so I began to think more about the conflicted impulses of “America’s Playground” and those of contemporary society.

Still from Mr. Robot

My mixture of piqued interest and near complete ignorance is what drew me to San Antonio’s McNay Art Museum recently to see a traveling exhibition illuminating Coney Island’s history as reflected in visual artworks, still and motion photography, and artifacts. Now in its final weeks at the McNay, Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861-2008 was organized by curator Robin Jaffee Frank of the Wadsworth Museum of Art. Inspired initially by Futurist painter Joseph Stella’s Battle of Lights, Coney Island, Mardi Gras (1914), Frank has assembled an impressively large and eclectic, thematic collection of paintings, drawings, prints, photographs, film clips, painted signs, carved carousel horses, objects from old games and shooting galleries, and more. She’s also pretty nicely navigated the inherent difficulties of traversing a century and a half of various high art, pop culture, and historic elements.

The show is organized in chronological sections, following the history of Coney Island from its beginnings in the mid-19th century as a watering hole for the wealthy, to an entertainment mecca for the masses, and finally through its long decline beginning in the mid-20th century. (All of this history, by the way, was much earlier than I’d previously thought—beginning before subways, modern cars, and the Brooklyn Bridge… . Before cinema even, and still early in the development of photography.) While the exhibition celebrates the spectacle of Coney Island and the condensed microcosm of “modern” American experience that its attractions and crowds presented to artists, it thankfully doesn’t sugarcoat or ignore the more uncomfortable aspects of commercialized spectacle at the famous beach destination.

Two depictions of Luna Park. L: Film still, Coney Island at Night, 1905. Camera: Edwin S. Porter. R: Joseph Stella, Battle of Lights, Coney Island, Mardi Gras, 1913-1914. Oil on canvas, 77 x 84 3/4 in.

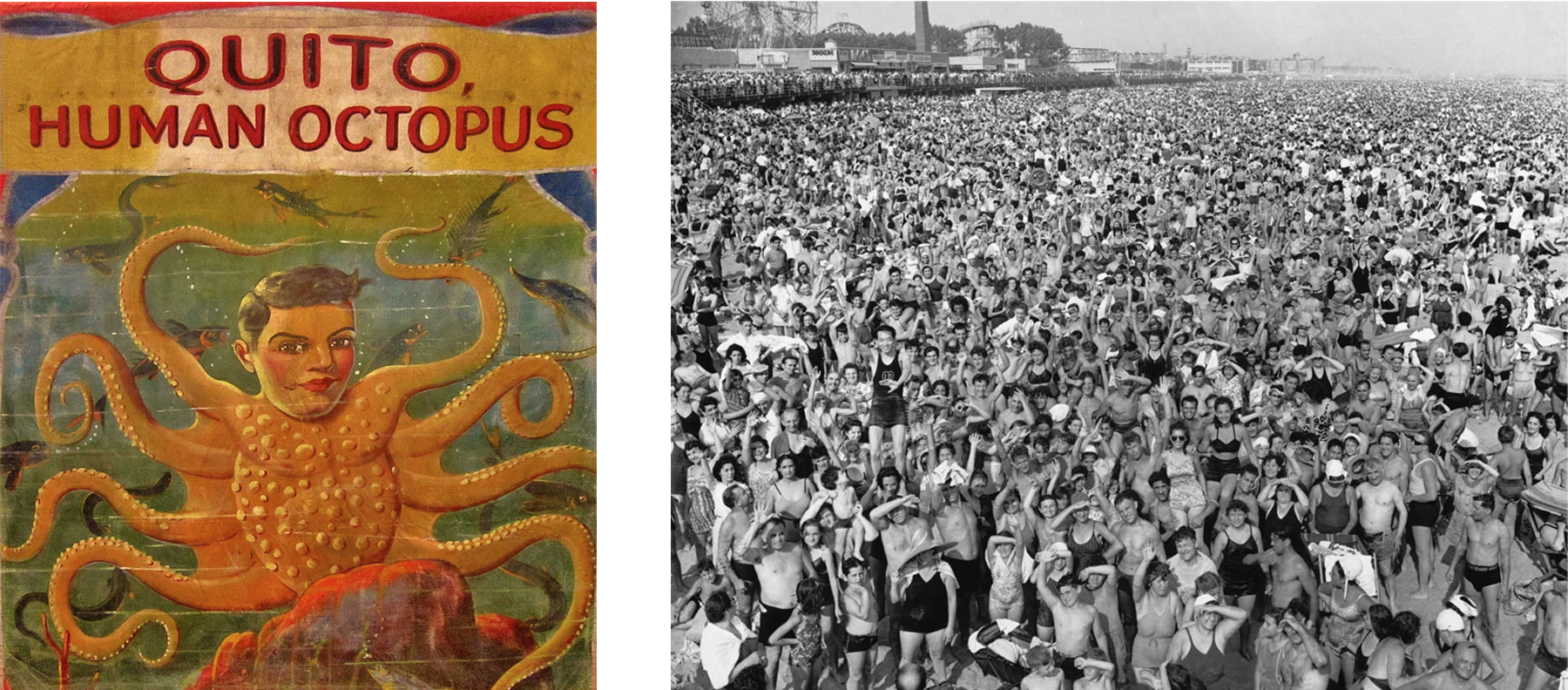

At the entrance of the show (before its chronology begins) are two powerfully huge and beautiful older paintings. I was taken by the style and balance of these large portraits, by the humanness of their science fictions, and by what struck me as interesting and surreal expressions of emotional/psychological hybridity. Though I knew it, I had to back up and take a moment to let it sink in: these are not simply evocative artworks, but also historic banner advertisements for actual, live Coney Island sideshows in the early 1940s.

One of the attractions featured the legless Jeanie, “living half girl,” (a common sideshow exploitation of disability) and the other featured Quito, the “human octopus” (which likely exploited audience gullibility with a theatrical illusion of some kind). These were exoticized half-truths sold as windows into reality. They were little things made big. What I was seeing here in these banners—what had long outlived the actual attractions and what was perhaps always most important—was their creative branding. Imaginative avatars and artisan clickbait. Coney Island was a lot like the internet.

I thus made a calibration in my approach before proceeding: I should view the contents of this show as reflections of layered simultaneous realities. I should take none of these things—even observational photographs—as simple actualities, but rather take all views as fun-house mirror distortions and explore their odd intersections. The storied venue for wild rides and sensational bamboozlement is now itself the star of the show.

L: Quito, Human Octopus, 1940. R: Weegee, Coney Island Beach, 1940

“What attracts the crowd is the wearied mind’s demand for relief in unconsidered muscular action… We Americans want either to be thrilled or amused, and we are ready to pay well for either sensation.” These are the words of George C. Tilyou, creator of Steeplechase Park, which along with Luna Park and Dreamland made Coney Island a booming destination beginning around the turn of the 20th century. The unusual structures, electric lights, and roller coasters of these parks were dazzling, new technological feats at the time. The multi-sensory spectacles and designed movements of participants through spaces, the perspective shifts, and the physical jostles were new types of interactions, too. The bulk of the works in the McNay show are from this heyday (roughly between the 1890s and the 1950s) and seeing the wide range of works together is appropriately stimulating.

One can momentarily forget the timeline, the impressive amount of important artists included, and the boldness of the show’s montage-style arrangements: Samuel Carr beach scenes next to a Barnum & Bailey water carnival poster; photographs by Diane Arbus and Walker Evans and Garry Winogrand and Robert Frank and Yasuo Kunoshi. Paintings by both Joseph Stella and Frank Stella! All that and more, overseen by a high-hung, painted metal sign of the “Funny Face”—the iconic man with the unnaturally stretched smile who, in larger form, overlooked Coney Island for many decades. Weegee’s New York (1954) captures voyeuristic color film footage of women’s bodies on the beach, while photographer Morris Engle’s The Little Fugitive (1953) more naturally documents in black and white Coney Island’s bustling life from the perspective of a lost little boy. Still photographs, while vastly different, tend to focus on the people as much or more than the place, capturing gestures, interactions, and changing fashions and demographics on Coney Island’s beaches, boardwalks, and streets over time.

L: Reginald Marsh, Pip and Flip, 1932. Tempera on paper mounted on canvas, 48 ¼ x 48 ¼ in. R: Sue Coe, Side Splitting Fooleries: Edison Tests the Electric Chair on an Elephant, 2007, graphite, gouache, and watercolor on board, 40 x 54 ½ in.

The final section of the show covers the long decline, decay, and contemporary reconsideration of Coney Island between the early-‘60s and late-2000s. This was, for me, the rollercoaster’s long, slow return to the platform, when the world stops spinning but one’s eyes and stomach don’t. I was in more familiar territory here in the haze of this chapter, titled “Requiem For A Dream,” after Darren Aronofsky’s bleak, drug-addled Coney Island film from 2000. It’s difficult to imagine a darker dream-killer than clips of that film, but the darkest and most powerful coupling in the show is a 2007 carnival-style, American flag-filled painting by Sue Coe referencing the horrible, true occurrence of Thomas Edison’s public electrocution of a live elephant on Coney Island in 1903 (a publicity stunt to discredit his competitor’s new form of alternating current electricity), next to a monitor showing the disturbing film footage of the actual killing of the massive animal.

I’d heard the story of Topsy the elephant before, and had even wondered if this traveling celebration of Coney Island would be brave enough to address the dead elephant in the room. But I was still not quite prepared for this smart break of the show’s chronology clustering a dark, referential contemporary work of art with a shameful film document from a century earlier. Coe’s piece called back to the sideshow banners I’d seen at the show’s entrance, and blurred the loops I’d travelled in between.

I know that the average visitor to Visions of An American Dreamland is seeking more the nostalgia and sense of wonder associated with the place than looking at its underbelly and contemporary relevance. I saw both. The darkness in Coney Island’s weird, 150-year experiment doesn’t cancel out the great deal of very real delight there. These layered, simultaneous realities are woven into the delicate suspension that is contemporary America.

Electric amusement, branded spectacle, and modern, mass-market entertainment as a whole were largely born in that waterfront land of distractions, for better and for worse. These kinds of conflicted origins, suspended frictions, and interconnected extremes are, frankly, what any aware American must acknowledge and grapple with. As I ran the show in reverse, going back through the galleries in a flipped chronology, I thought about how I’d been lured to the show for the same reasons that artists had always been drawn to Coney Island. I waved to the iconic Steeplechase “Funny Face” sign on my way out, and thought to myself: That guy has seen it all.

Through Sept. 11 at the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio.