Installation view of “Vincent Valdez: Just a Dream…,” with “The City I and II.” Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

In a mid-career survey exhibition that fills both floors of the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston (CAMH), Vincent Valdez’s (b. 1977) “Just a Dream…” demonstrates a dazzling mastery of the human form, keen sensitivity to social and political injustices, and – with his finger always on the pulse of American culture – a remarkable handling of allegorical narratives and political reportage. Showcasing over 200 works that span a quarter century, this exhibition is the most comprehensive outing to date of the San Antonio native who now splits his time between Houston and L.A.

Introduction

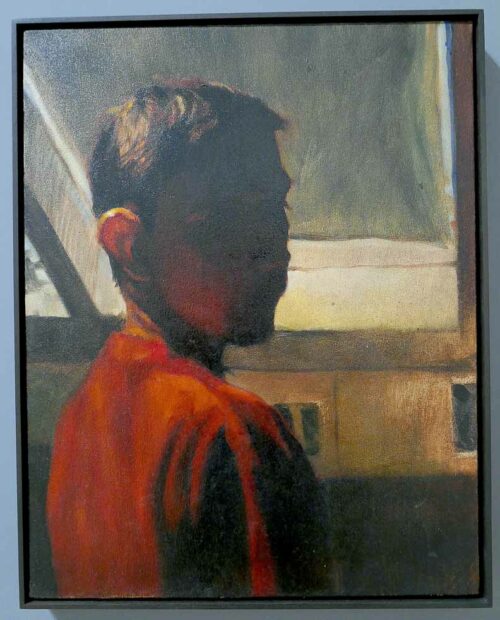

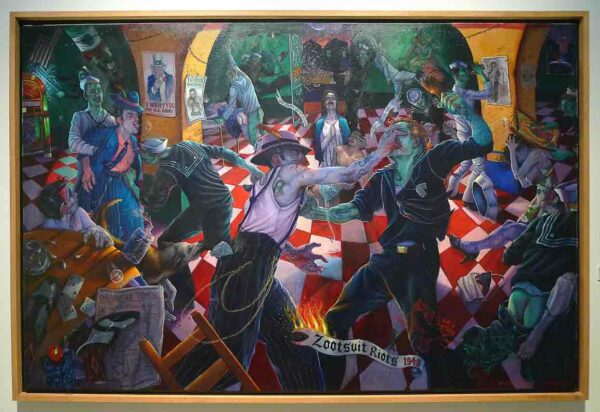

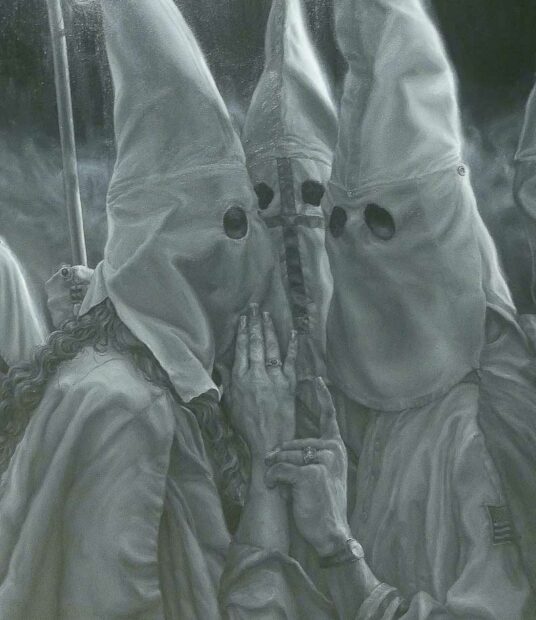

Valdez burst onto the artistic scene with Kill the Pachuco Bastard! (2001), a large oil painting that dealt with the Zoot Suit riots of 1943, when U.S. servicemen (and others) attacked flamboyantly-dressed Mexican Americans in Los Angeles. Created when he was a senior at The Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), the painting was one of the highlights of “Chicano Visions: Painters on the Verge,” the exhibition of entertainer Cheech Marin’s collection that opened at the San Antonio Museum of Art in 2001. In 2016, Valdez completed The City I, a stark, monumental painting of robed, contemporary Klansmen assembling on the outskirts of a city. The painting’s relevance was demonstrated by a succession of events: on July 17, 2015 (before the painting was begun), a white supremacist who had posed with the Confederate flag murdered nine black parishioners in Charleston, South Carolina; former Klu Klux Klan (KKK) Grand Wizard David Duke endorsed Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign; the 2017 “Unite the Right” white supremacist rally in Raleigh, North Carolina (countering demands for the removal of Confederate monuments), erupted in violence, shining a lurid light on racist extremism, its perseverance in U.S. history, and the dangers posed by contemporary white supremacists.

Valdez made art almost from the crib. His first preserved drawing dates from when he was three years old (illustrated in the exhibition catalog, p. 65). An image of an ugly duckling, it was already a work of social commentary, rendered by someone who considered himself an outsider. When Valdez was five or six, after flipping through 90 TV channels and not finding anyone who looked like him, he became confused: “I asked my mom… if I was American” (“Video interview with Vincent Valdez,” Vincent Valdez, The City, 2018, The Blanton Museum of Art).

Valdez painted his first politically engaged mural in San Antonio when he was in the fifth grade (at the Esperanza Peace and Justice Center). See a film clip of this mural, on the topic of nature, which features bombers dropping napalm. The eleven-year-old artist queries whether people (including himself) “will still be around” to experience nature in the near future (see: “Vincent Valdez – Tuesday Evenings with the Modern Lecture Series,” Modern Museum of Fort Worth, March 8, 2022).

When Valdez was nine or ten, he was mentored by an eighteen-year-old Alex Rubio (who now goes by the name Rubio Rubio). Together, the duo (Valdez often referred to himself and Rubio as a kind of “Batman and Robin”) completed numerous murals in housing projects through the Community Cultural Arts program. After high school, Valdez won a scholarship to RISD, and he proved himself to be a formidable artist during his undergraduate days.

Remembering, 1999

Vincent Valdez, “Remembering,” 1999, house paint on board, collection of Joe A. Diaz. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

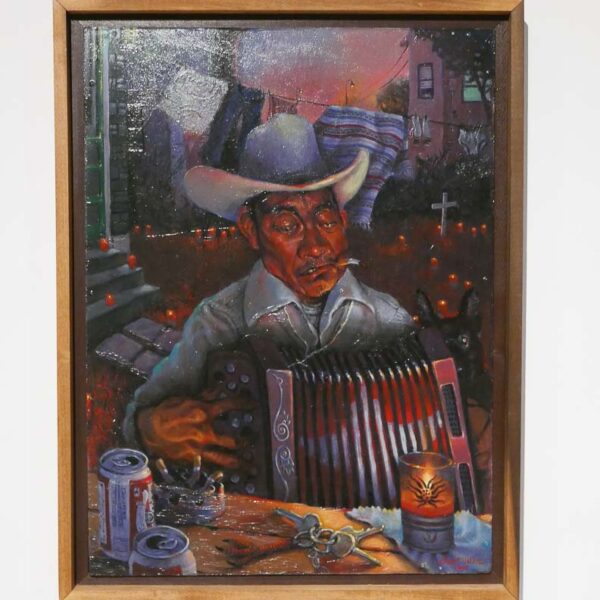

Remembering (1999), Valdez’s earliest painting in the exhibition, was done during his junior year at RISD, when – despite his longing – he could not return to San Antonio for Thanksgiving. College was Valdez’s first extended period away from San Antonio, and it was this absence – as well as the cultural shock of living in New England – that led the artist to conceive and produce an image of “what home was.” Before RISD, he did not know that other states were unlike Texas, and that breakfast tacos and conjunto music were not national norms.

Valdez depicted an elderly man (inspired in part by his grandfather) in a South-side-of-San Antonio backyard who is smoking, drinking Budweiser, and playing an old accordion with gnarled hands, while the cross hanging from his neck rests on the bellows. (Valdez is himself an avid musician who has played in several bands). The man’s keys are attached to a chicken’s foot, laundered clothes are drying on the line, and a white cross marks his loyal dog’s final resting place. Valdez, in fact, characterizes the dog as the man’s “only true friend.” Therefore, this is particularly hallowed ground. The man’s eyes are rather blank, and his face is twisted as he reminisces about his departed dog. Memory, emotion, and particular, personalized objects serve to create a unique sense of place, a vivid world, a tiny universe that is whole unto itself.

Vincent Valdez, “Remembering” (detail), 1999, house paint on board, collection of Joe A. Diaz. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Drinking, smoking, and music-making are likely daily rituals in this backyard. The votive candles, Valdez explains, are not real – they are hallucinatory. Sprinkled throughout the backyard, there are multiple points of light that commemorate and honor the departed canine, creating marvelous painterly effects (to which reproductions do not do justice). The dog itself is thereby resurrected. It sits attentively behind the accordion, ears perked in rapt attention. Upon close inspection, the eyes of the man and the eyes of the dog are quite similar. This uncanny resemblance underscores their unique kinship. It also suggests that we are seeing the dog through his mind’s eye. The man’s deep feelings – and his music – have both altered the landscape and summoned the dead, bridging the gap between the quotidian and the supernatural. In a furious two weeks of painting day and night with ordinary house paint, Valdez thereby bridged the gap between Providence, Rhode Island and San Antonio, Texas. (For Valdez quotes, see my text in ¡Arte Caliente! Selections from the Joe A. Diaz Collection, Corpus Cristi, TX: South Texas Institute for the Arts, 2004, p. 40.)

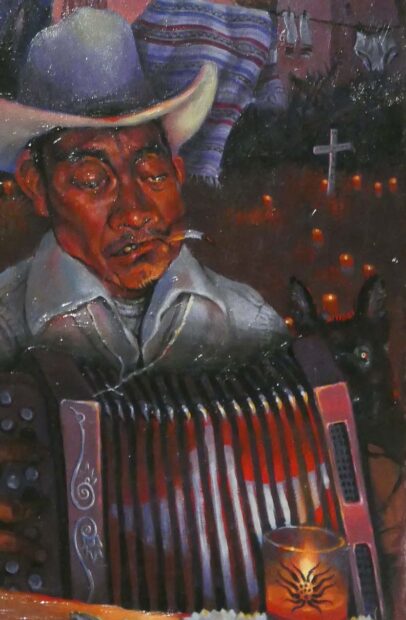

Vincent Valdez, “Red Ear (Twenty-One Years),” 1999, oil on canvas, collection of the artist. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

The artist presents himself here, at a mere twenty-one-years-old, in a rather comic vein, with light striking and highlighting a cartoonishly projecting ear. His forms are simplified, his face lost in shadow. Deliberately or not, the background reminds me of a Diebenkorn, while the figure itself recalls summary forms found in works from the Bay Area Figuration group. Valdez appears more like a young David than a Goliath, though, unlike conventional images of David, his eyes, his expression, and his thoughts are shielded from us, with shadow serving as armor against the viewer’s inquisitorial scrutiny. Perhaps the David analogy is apt: soon, the artist would take his best shot (in the form of Kill the Pachuco Bastards!) at the artistic establishment that had long denigrated figural art. The harsh criticism he received from an antagonistic professor that upheld “the RISD creed” also served as motivation.

Kill The Pachuco Bastards, 2001

Vincent Valdez, “Kill the Pachuco Bastards,” 2001, oil on canvas, collection of Cheech Marin and The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture of the Riverside Art Museum, California. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Valdez was inspired by the depiction of the Zoot Suit Riots at the beginning of the film American Me (1992, dir. Edward James Olmos), which is how Valdez learned of this historical event. In American Me, Esperanza (Hope) travels to a tattoo parlor, where her boyfriend Pedro has just tattooed his arm with her name and the phrase por vida (for life). Suddenly, sailors burst into the shop and separate the couple. They take the Pachucos outside. Along with soldiers and police, they beat the young men, cut their hair, and strip their clothes off. One of the zoot suiters is tossed through the shop window. In the meantime, sailors gang-rape Esperanza inside the parlor.

In Valdez’s painting, multiple Pachucos are being beaten (or have already been beaten) while two women (in the left background and the right foreground) are being raped. In the center background, recreating an event from the film, a Pachuco is being thrown through the window. All the violence in Valdez’s painting, however, is taking place within a Mexican American bar, which has essentially been invaded by sailors. (For a lengthier treatment of the riots and of Valdez’s painting, see my 2023 Glasstire review “Texas in Riverside: ‘Cheech Collects’ at the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art and Culture, Riverside, California”).

In my review of the Chicano Visions exhibition at the San Antonio Museum of Art, I referred to Kill the Pachuco Bastards as

… surely the show’s edgiest work. It depicts a no-holds barred bar-fight in which rapacious sailors savage a Pachuco joint in 1943. They violate every Chicano body and cultural emblem with unremitting barbarity. The painting is remarkable for: the dynamic expressiveness and superb characterizations of its varied protagonists, the lurid lighting effects, the complex space (including a tile floor that “rolls” like waves on an ocean) and the undeniable mastery that makes it possible to pack such dense (and meaningful) iconographic details into a compelling, clearly legible narrative (Voices of Art, vol. 10, #1, 2002, p. 16-18).

With this painting, Valdez proved himself to have the rarest of talents: he is a history painter, one capable of carefully placing each and every protagonist in the most telling pose, pregnant with symbolism, political meaning, and high drama. The careening perspectives, the garish colors, the jagged forms, and the degree of sheer physical torment recall signal German Expressionist works. From a wealth of artistic sources, including several leading Chicano artists, and a whole host of American painters from the first half of the twentieth century, Valdez has created compelling, expressive theater. He could easily have made a photorealistic work, but what he has created is far more compelling because of its mix of strange accents, distinctive characterizations, superb stylizations, and its air of macabre horror.

Valdez has underscored the racism, sadism, and xenophobia of the invading sea-farers. On the left, a sailor smashes a jukebox while another tears down a Mexican flag. On the right, a sailor smashes an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe on the head of a desperate, partially-stripped woman. The sailors explicitly attack race, culture, and religion. Their goal is to dominate through humiliation and degradation by beating, stripping, breaking, and raping. The savagery of these actions belie their putative pretext, that zoot suits wasted fabric during wartime austerity. Pachuco patriotism is expressed through the display of the American flag, and James Montgomery Flagg’s Uncle Sam Wants You for the U.S. Army recruitment poster. In refutation of the offer made in the poster, the sailors clearly regard Pachucos as internal enemies, rather than potential conscripts.

It was quite a stupendous feat, for an artist as young as Valdez to make something like Kill the Pachuco Bastards! The painting is as remarkable for its technique as for its political content. Nothing quite like it existed. It answered the challenge posed by Leonard Long, his RISD professor, to create something great for his senior project. Kill the Pachuco Bastards! enthralled visitors to the Chicano Visions exhibition. Additionally, on the basis of this work, the other artists featured in the exhibition immediately regarded Valdez as a peer rather than an emerging or neophyte artist.

Valdez traveled with Chicano Visions during its run from 2001-2007, during which time he had occasion to speak with many communities about the Zoot Suit Riots.

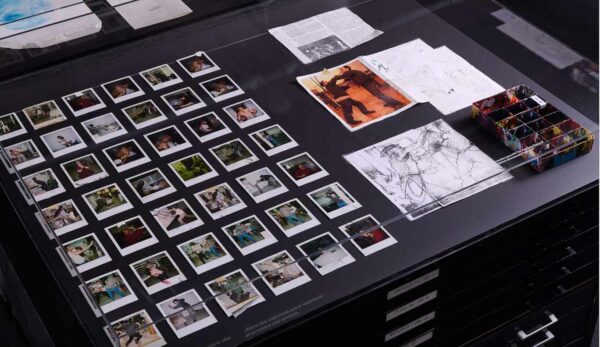

Installation view of “Vincent Valdez: Just a Dream…” (with studies for “Kill the Pachuco Bastards!”), courtesy of Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, 2024. Photo: Peter Molick

I am very appreciative of the studies for Kill the Pachuco Bastards! that were on view in the exhibition. They include 42 polaroids, with Valdez serving as the primary model (even for the robed Madonna-like figure in the center of the painting), and the sketches visible on top of the black flat file in the above photograph.

Valdez utilized newspaper articles for research, such as the one from the Los Angeles Times illustrated in the lower left corner of the painting. It’s an interesting psychological phenomenon that Valdez put himself in the place of these various figures. Perhaps imagining and pantomiming their actions enabled him to depict them with more credible agency. If he made a full-scale study for the painting, I would love to see it.

The flat file (most of the drawers can be opened) holds many of the artist’s earliest drawings and press clippings, as well as an assortment of later works. I am disappointed that CAMH did not include more early works in the “Just a Dream…” exhibition, especially since this period includes some of Valdez’s greatest achievements. The charcoal drawing With a Little Luck, Faith, God, and a Six Pack (2001) foregrounds a punkish boxer within a 1940s tableaux. As in many of the artist’s best works, surreal elements have a powerful effect, including fighting cocks that spring from the skinny boxer’s mohawk, as well as several floating signifiers (including beer cans, a disembodied heart, and an image of Christ) that populate the top of the drawing. In I Lost Her to El Diablo, an oil painting from 2003, Valdez perfected the bar room lighting effects we saw in Kill the Pachuco Bastards! While addressing “The Devil at the Dance” folklore, he also made a psychological and symbolic leap by transmuting and externalizing his troubled protagonist’s thoughts into neon signs. (For these two works, see ¡Arte Caliente!, cover, and p. 42-43).

Stations, 2001-4

Installation view of “Vincent Valdez: Just a Dream…” (with four drawings from “Stations” on the left, and the painting “Just A Dream (In America)” on the right), courtesy of Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, 2024. Photo: Peter Molick

The CAMH venue features four of Valdez’s 13 graphic works from his remarkable Stations (2001-4) cycle. They were born of the artist’s short-lived participation in a sparring club with no weight classes (when he was at RISD), one in which the artist’s only goal was to survive each bout. This experience provided the imagery for Valdez to narrate the “story of the underdog,” the quixotic man who struggles against all odds simply because he can, undaunted by the prospect of almost certain defeat.

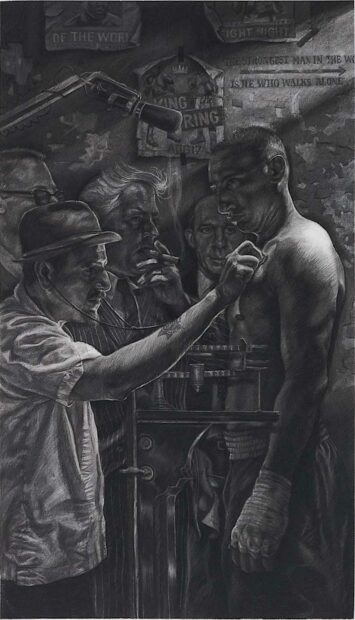

Vincent Valdez, “Stations: Weigh In, Coming in at 140lbs, 8oz,” 2001-4, charcoal on weave paper, collection of Mike Loya. Photo: Vincent Valdez website

Boxing is the most solitary and dangerous of sports. The boxer risks serious injury – and even death – every second between bells. Each of his opponent’s swings has malevolent intent, and every blow is potentially lethal. Brain damage and impaired motor function are among the sport’s deleterious long-term effects. In her essay titled “On Boxing” (reprinted in the catalog), the poet Joyce Carol Oates points out the self-sacrifice boxing requires, “the punishment – to the body, the brain, the spirit – a man must endure…” Boxing is an accelerator of mortality: Oates notes that the toll of punishment in the ring “in even a young and vigorous boxer is closely gauged by his rivals…” (p. 99).

But boxing’s pageantry and the high drama of its rituals – precisely because it is an individual sport that poses mortal risks at every outing – are unmatched. Oates emphasizes that boxing is at heart “a story – a unique and highly condensed drama without words” (p. 82).

She adds that boxing is “not a metaphor for life, but a unique, closed, self-referential world, obliquely akin to those severe religions in which the individual is both ‘free’ and ‘determined’ – in one sense possessed of a will tantamount to God’s, in another totally helpless” (p. 96). Boxing is an intensification of life, marked by the bell and dosed out in three-minute intervals.

Valdez recognized parallels between boxing narratives and the central narrative of Western art: The Passion of Christ. The weigh-in functions as boxing’s Ecce Homo moment, the ring itself is its Golgotha.

Vincent Valdez, “The Strongest Man is He Who Walks Alone,” 2001-4, charcoal on paper, collection Mike Loya. Photo: Vincent Valdez website

In the above image, the hooded boxer encounters his own image on a T-shirt, echoing the miraculous image of the Sudarium, the bloody, sweaty face of Christ captured by Veronica on her veil, after one of Christ’s falls. Valdez thereby dramatizes the boxer’s walk to the ring.

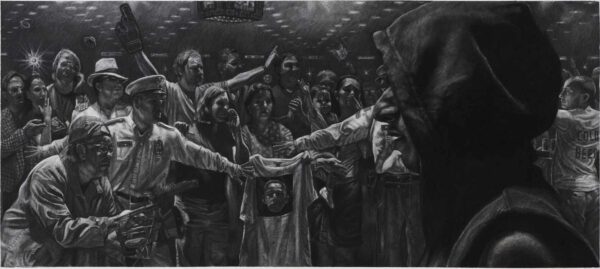

Vincent Valdez, “They Say That Every Man Must Fall,” 2001-4, charcoal on paper (not in CAMH exhibition). Photo: Vincent Valdez website

The boxer’s falls can be likened to Christ’s falls (when carrying the cross). In the above image, ghostly images of Christ appear twice: directly behind the boxer’s head, he is upright, wounded and bloodied, but living; at the boxer’s feet, he is supine, apparently dead on the cross. The dazed boxer visualizes these two possibilities while he struggles to resurrect himself.

A knock-out is a boxing death; rising up from the canvas is analogized to Christ, who rose up multiple times on his path to Golgotha. Valdez is not simply equating the boxer with Christ, rather, the two grand narratives (those of boxing and those of the Passion) are fused to dramatize the story of the indefatigable underdog. Valdez’s boxer (modeled on his brother Daniel) is no god. He is just a man – and one of low status at that. But his bout is a chronicle of resistance per se, and Valdez here elevates and sanctifies that resistance by reference to religious tradition.

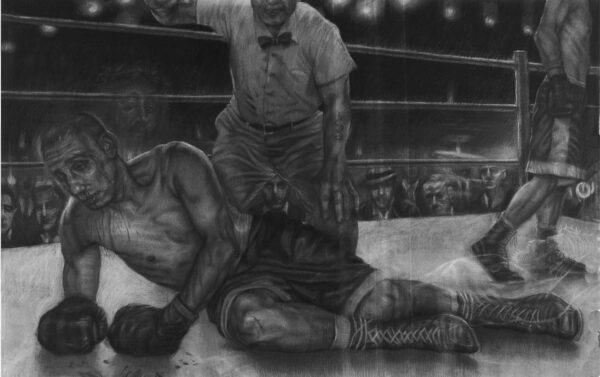

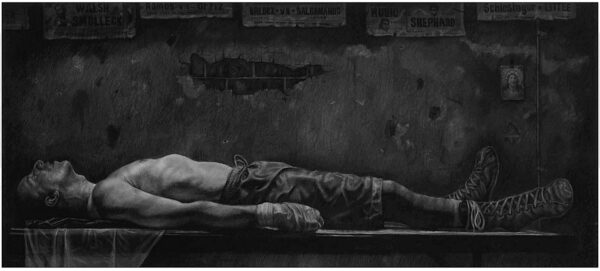

Vincent Valdez, “Stations IX: Laid Out,” 2001-4, charcoal on paper, collection Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo: Vincent Valdez website

The fighter is knocked out, temporarily stilled, momentarily dead to the world. In this state, he resembles some images of the Dead Christ, though Christ is rarely rendered from this perspective (most memorably by Hans Holbein the Younger in 1521). The small photograph of Christ taped above the boxer’s feet underscores Valdez’s Christological parallel. The image is based on a head of Christ painted by Valdez’s great-grandfather, Jose Maria Valdez, in 1898 (illustrated in the exhibition catalog, p. 64).

Oates declares, rather tendentiously, that “boxing is about being hit rather more than it is about hitting, just as it is about feeling pain, if not devastating psychological paralysis, more than it is about winning” (p. 111). Whether or not that is the case for boxers in general, it is certainly true for Valdez’s K.O.-ed underdog. He has fought the good fight, and he has paid the price. It is for that reason that he lies here before us.

“Stations” was the subject of Valdez’s first one-person show, held at the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio in 2004. The exhibition wowed the public and had the great advantage of being exhibited without glass (the highly reflective glass at CAMH made these drawings impossible to see well).

Made Men, 2002

Vincent Valdez, “Made Men: They Say Every Man Must Need Protection,” “Made Men: They Say Every Man Must Fall,” “Made Men: Yet I Swear I See My Reflection,” “Made Men: Any Day Now, I Shall Be Released,” all four 2002, pastel on paper, collection of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

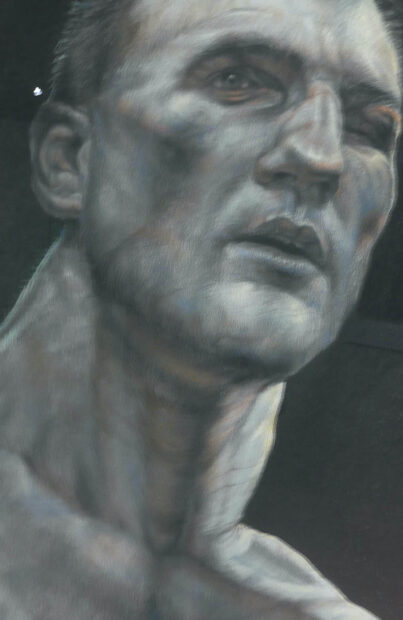

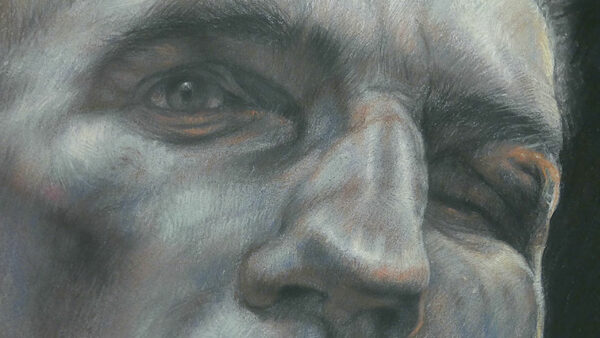

Near the beginning of the lengthy interim in which he made “Stations,” Valdez also created what may be his most remarkable series: the “Made Men” (2002). It consists of four enormous male busts, which are highly particularized, based (partially at least) on real people, and symbolically resonant. The four monumental heads are archetypal figures in Western art and culture. The first three are paradigms of heroic masculinity.

Let us consider what the term “made men” meant for Valdez in the context of this series. As noted in the 2022 “Tuesday Night” lecture, the artist came to this term through rap music, where it signified someone whose life, like that of a “made” mafioso, “was assured.”

Here we might also think of the first three “Made Men” as referring to social constructs. They are men who are fitted into pre-existing patterns, and these archetypes subsume them, forcing them to conform and to perform.

Vincent Valdez, “Made Men: They Say Every Man Must Need Protection” (detail). Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

The first of these men is a musclebound boxer, one that recalls examples of heads in mid-century American works. (On the basis of Sharky, painted in 2000 – illustrated in catalog on p. 68 – we can trace this figural type back to George Bellows.) This boxer’s neck is itself a bulging muscle. His face is a gnarly landscape – direct evidence of his chosen profession. His left eye has been punched shut. His nose has been broken numerous times. His ear is “cauliflowered” from multiple blows that have hammered down on it.

Vincent Valdez, “Made Men: They Say Every Man Must Need Protection” (detail). Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Upon closer inspection, there is blood on the swollen left eye. By implication, the red-orange tint on other parts of his face could also represent blood. This face is a battleground, one that has survived a number of grueling campaigns. Notwithstanding the man’s hulking physique, his one open eye conveys trauma, pain, and fear. Since his left eye is not bandaged, we can assume that he is still in the ring, warily eyeing his opponent – and perhaps an incoming punch.

The second of Valdez’s Made Men is a martyr, represented by a typically Euro-American Christ figure (with European rather than Middle Eastern features). The fact that this is an image of Christ in particular is evidenced by the puncture wounds in his forehead, left by the crown of thorns that was mockingly thrust onto his head. His lips are parted, and his bloodshot eyes gaze heavenward. Fluid flows from his right nostril, a sign that he is on the cross, and unable to wipe it. From his look of despair, this could be his “Why hast thou forsaken me?” moment.

The third of these men is a soldier with a dirty face and a severe crew-cut. He is sweaty and tense. The dark form in the center of his right cheek seems to mimic or reflect an explosion. Tracers light up the sky, perhaps aiding the course of a bullet that will bear his name. His fearful eyes and countenance are wholly appropriate for the moment in which he is situated.

It was, in fact, a documentary film on the Vietnam War that, more than anything else, gave rise to this series by causing the artist to reflect on masculine role models. As a child, Valdez was vexed and confused about the fact that his father was drafted into the Vietnam War and compelled to serve against his will. War – and issues related to it – weighed heavily on the young man. Valdez taped – and obsessively rewatched – a documentary film called Dear America: Letters Home from Vietnam (dir. Bill Couturié, 1987).

When it came time to create the Made Men series, Valdez reflected on a sequence in Dear America that included a furious firefight (with artillery and machine guns), massive fires in urban and jungle areas, and a soldier’s harrowing description of attempting to identify the body of a fallen friend. The musical accompaniment was The Band’s haunting and elegiac rendition of Bob Dylan’s “I Shall be Released.” Valdez was deeply moved by this combination of words and images (see the 2022 “Tuesday Evenings” lecture at the 25-minute mark). Moreover, Valdez wanted to wed image and text in his work. His solution was to embed text on the neck of the last of the four men.

The last of the “Made Men” is a contemporary urban male, “a street kid, or homie,” as Valdez describes him. He is also modeled by the artist’s brother, Daniel. At least on the surface, he may seem insouciant. But he is anxious about how to behave in a changing world governed by uncertainty, with the concomitant loss of traditional directives and norms. He looks to the left, surveying the three archetypal male role models with skepticism. He desires to find his own path.

Valdez’s verbal commentary is the final line from the chorus of Bob Dylan’s “I Shall Be Released” (1967), which appears as a tattoo on the young man’s neck:

I see my light come shinin’

From the west down to the east

Any day now, any day now

I shall be released

In the context of this series, the verse before the final chorus also appears to be particularly relevant to this young man’s situation:

Now, yonder stands a man in this lonely crowd

A man who swears he’s not to blame

All day long I hear him shouting so loud

Just crying out that he’s been framed

He’s a young man, in a lonely urban crowd, who does not want to be “framed:” he refuses to be boxed into one of the conventional male archetypes.

We might also note the relevance of other lyrics as commentary on all four of these monumental drawings, particularly the second verse:

They say every man needs protection

They say that every man must fall

Yet I swear I see my reflection

Somewhere so high above this wall

Significantly, the lights above the heads of these men carry individualized symbolic meanings. The boxer is framed by arena lights, where he must make his solitary stand within the ring. The martyr witnesses falling stars, commonly associated with end times and terrestrial apocalypse. As noted above, the tracers above the soldier could be the death of him. The young man’s head is framed by street lamps. Alone in the crowd, he does not yet know where to go, or how to act.

These four men represent masculine options. Though male archetypes are, by tradition, exemplary figures of strength and invulnerability, Valdez has depicted these representatives of manhood at their most vulnerable and their least confident.

Valdez provides an analysis of the series in which each man has an epiphany, a moment of truth, a flash in which he grasps his individual, unique fate, which he desperately seeks to escape:

They become Frankenstein men. They are the new Frankenstein modern-day creations. Products of a society. Created by society for the use of society – until society is finished with them. [Then] they are discarded and forgotten. Even though each one realizes that all odds are stacked against them, that the fix is already in, they stand defiant… and with a bit of spark in their eye, thinking that they may still… find a way out (“Tuesday Night” lecture).

These modern ‘monsters” are created by society in order to be used and destroyed.

Valdez excels in exploring (often quirky) aspects of contemporary masculine identity. One of the most interesting is a pastel titled Yo Soy-ee Blaxican (2003, illustrated in the catalog, p. 69). The title stems from Daniel’s response when Vincent asked him what racial category he utilized at school. Daniel had no experience of Mexico or of the Chicano movement, and he did not identify with the terms Hispanic or Latino. On the other hand, Daniel revered rap music and Tupac Shakur, so he spontaneously invented his own category, which became the title of the piece. Valdez also created a sardonic series called “Flirting Tips for the New Millennium Male,” that spoofed 1950s etiquette books he encountered in a used bookstore. Modeled by Daniel (the artist’s quixotic protagonist in many early works) and his circle, the series drew heavily on Catholic iconography, transposed into modern-day San Antonio. Valdez also created works that explored racial and youth profiling by the police. A sampling of these works would have greatly enhanced the exhibition.

Expulsion, 2002

Vincent Valdez, “Expulsion From the Great City,“ 2002, charcoal on paper, collection of Mollie Middleton. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Expulsion From the Great City is part of the “Made Men” series. It can symbolize a potential (and very unhappy) path taken by the final made man. Riffing on the Christian theme of the expulsion of Adam and Eve from paradise, Valdez renders an anonymous, modern-day Adam and Eve, who, naked to the world, are making a forced exit from a great metropolis. Modeled on the artist and his partner at the time, this twenty-first century Adam and Eve stand on the edges of weathered, board-like ledges, as if they were convicts on a ship, condemned to “walk the plank.”

Perspectival traces of a great boulevard – in the form of streetlights – manifest themselves as triangular wedges behind their heads, which are cropped at the top. This cropping serves to deny specificity and individual identity. These are not foundational mythic figures, like the Biblical Adam and Eve, whose actions reverberate throughout Christian history. They are not bearers of curses. Nor – despite their great scale – are they founders of a new nation.

Vincent Valdez, “Expulsion From the Great City“ (detail), 2002, charcoal on paper, collection of Mollie Middleton. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

That is not to say that these two figures are not allegorical. They are an Everyman and an Everywoman. They are everyone, but they are no one in particular. They are modern misfits, retreating (against their will) from the city, each of them, judging from their gestures, blaming the other for their loss of home and habitat.

They are not situated on the edge of a lush, mythic paradise, but rather on detritus-filled ledges. The woman’s feet are framed by McDonald’s french fries, an apple core, crumpled pieces of paper, cigarette butts, and a couple of pennies. And, in this story, a partially eaten apple is no more significant than an unconsumed french fry.

The man’s feet are framed by an empty beer can, a used condom, cigarette butts, and a newspaper. Like that paper, he is “yesterday’s news.” At least he also has a couple of pennies for his thoughts.

Similar to the other depicted articles, this pair of humans also serve as discarded objects of little value. They, too, have been swallowed up and spit out by the Great City. This couple is without means, without concord, and without destination. They have no place. Not in the modern world, and not in the one that preceded it.

And Now for Something Completely Different: El Chavez Ravine, 2005-7

Installation view of the bottom floor of “Vincent Valdez: Just a Dream…,” with “Burn Baby, Burn,” “El Chavez Ravine,” and “Kill the Pachuco Bastards!” Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

The musician Ry Cooder had been looking for someone who could tell the story of Chavez Ravine on the body of a vintage ice cream truck. Because of its scale (larger than a car), its interesting shape (better than a van), its legacy of mobility (ice cream trucks went into every neighborhood), he imagined such a truck would make an ideal, ambulant surface for his vision, since it would be bigger than an easel painting and more mobile and less vulnerable than a static mural. But who could bring this vision to fruition in paint?

Artist Rubén Ortiz Torres recommended Valdez, saying he was the only person in the world who could do justice to this project. When Ortiz Torres showed Cooder the reproduction of Kill the Pachuco Bastards! in the Chicano Visions catalog, he knew that he had found his man. Cooder couldn’t locate a vintage ice cream truck, so he had Duke’s So. Cal build one out of a 1953 Chevy “three-window job” and customize it into a lowrider.

After ignoring Cooder’s phone messages for six months (he was working incessantly on the Stations show for the McNay), Valdez called him back. “I thought he was completely insane,” recalls Valdez, “but I thought that I was able to match his insanity in terms of challenging yourself to tackle challenging subjects.” In 2005, Valdez moved to Los Angeles, where he spent two years collaborating with Cooder on the project (see: “In Conversation: Vincent Valdez and Ry Cooder,” Los Angeles County Museum of Art, August 9, 2024).

Vincent Valdez and Ry Cooder, “El Chavez Ravine” (rear view), 2005–7, oil on 1953 Chevy Good Humor ice cream truck, collection of Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Cooder wanted a critical history of Chavez Ravine, one that showed how predominantly Mexican American neighborhoods (Bishop, Palo Verde, and La Lloma), known as a “poor man’s Shangri La,” had been destroyed by the city of Los Angeles. New housing projects were approved in 1949, and residents received notification shortly thereafter. On the rear of the truck (illustrated above), the eviction notice of July 24, 1950, from the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles is written on the door, above the depicted mailboxes. As Valdez notes in the “In Conversation Valdez/Cooder” video cited above, he even matched the fonts on the bilingual notices (see detail of the door in catalog, p. 139).

Utilizing eminent domain, the city condemned and ultimately razed Chavez Ravine, ostensibly to build a public housing project to be called Elysian Park Heights. Displaced residents were to have first choice of the new housing. But the project was never built. Public housing – condemned by many in the 1950s as Communistic – became a victim of the Red Scare. A chief proponent of the Elysian Park Heights project had to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1952, and he was subsequently fired and jailed.

Vincent Valdez and Ry Cooder, “El Chavez Ravine” (right rear view), 2005–7, oil on 1953 Chevy Good Humor ice cream truck, collection of Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Characterizing public housing as “un-American” in his 1953 electoral campaign, the new mayor of Los Angeles later bought the land (steeply discounted) back from the federal government. In 1958, he sold it to the owner of the Brooklyn (New York) Dodgers, who moved his team to L.A. and built Dodgers Stadium on the site. The remaining families were forcibly displaced from Chavez Ravine in 1959, and Dodger Stadium opened in 1962 (see Zinn Education Project).

The above detail spans a decade, with giant faces of key politicians and other officials framed by a wheel-like arch with the City of Los Angeles writ large in neon. Inside of the arch, one catches a hallucinatory glimpse of the imaginary high-rises in the never-built housing complex. The black-and-white section features police forcibly removing a member of the Arechiga family on May 8, 1959 (televised nationally at the time, and screened at CAMH on the TV monitor adjacent to the truck). The family matriarch threw stones at the police, who oversaw the destruction of the Arechiga possessions and house. The next day, a Los Angeles Times headline blared: “Chavez Ravine Family Evicted, Melee Erupts” (see Janice Llamoca, “Remembering The Lost Communities Buried Under Center Field,” CODE SW!TCH: Race in Your Face, NPR, October 31, 2017).

Vincent Valdez and Ry Cooder, “El Chavez Ravine” (top of truck), 2005–7, oil on 1953 Chevy Good Humor ice cream truck, collection of Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo: Elon Schoenholz, exhibition catalog, p. 138

In the above view of the top of the truck, which can be viewed at CAMH – as at other venues – via a mirror on the ceiling (albeit in reverse), Valdez has created an image akin to a monster movie poster. Below the title “El Chavez Ravine,” two nefarious, supernatural-looking hands hold chains that function like puppet strings. They can also be interpreted as a critique of the eighteenth-century economist Adam Smith’s theory of the “invisible hand,” which held that the self-interest inherent in market forces generally and inadvertently benefited society.

The hands operate the infernal machine below. It’s just a bulldozer, but it seems like an other-worldly death machine, like something out of The War of the Worlds, operated by the devil himself. Like a giant tank, it crushes the tiny, matchbox-like houses as if they were mere toys (or Monopoly game pieces), and it sends cars and bodies tumbling into the air. In the foreground, people rush away from this scene of annihilation. The insubstantial houses pose no challenge, so the mighty, crushing claw reaches out for the panicked populace, who we hope will flee a little faster, before it is too late.

In his inimitable fashion, Valdez captures the horror of eminent domain, as it is utilized by politicians, who habitually employ it to crush communities of color. In the “In Conversation Valdez/Cooder” video linked above, Valdez recalls his father’s account of the eminent domain letter informing him that the family home would be destroyed for the construction of Highway 90 in San Antonio. Valdez also notes the destruction of the Aztlan and Victoria Courts housing projects in San Antonio, which were cleared to make way for the Alamodome sports stadium.

Vincent Valdez and Ry Cooder, “El Chavez Ravine” (detail of hood), 2005–7, oil on 1953 Chevy Good Humor ice cream truck, collection of Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo: Elon Schoenholz, exhibition catalog, p. 140-41

In this phantasmagoric detail, Dodger Stadium is already built, and filled to the brim with spectators, in curving stands that are colored red, blue, and purple. Players and umpires are on the field. Yet, on the left, a rickety (evidently partially bulldozed) house, some half-collapsed palm trees, and rebar-reinforced concrete rubble are also on the field. It’s a Field of Dreams in reverse. Instead of an “if you build it, they will come” scenario, some determined residents refuse to leave – ever. In surreal fashion, the neighborhood – or what is left of it – and the stadium coexist.

The rubble is accompanied by three inhabitants of Chavez Ravine. Two of them stand and wave their hats, as if they were greeting a distant friend – but here they seem to be perpetually saying goodbye to their former home. Even more bizarre, a third man is seated in a large easy chair, in front of an outfielder wearing number 16. He appears to be watching the game. As the NPR article cited above notes: “For the next week, the Arechigas camped in front of the rubble that was once their home.” These “out of time” people are family members who still refuse to be displaced by the stadium.

On the hood of the truck, the family members are engaged in an eternal vigil, rather than a short-term one. Since Valdez illustrated a luxury edition of Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five (1969), I will use a term from that novel. These three people have become “unstuck in time.” In the eternity of time, in order to pass some time, one man turns from wreckage to ballgame. The man on the far right in the above detail is a man watching the ruins more than the game.

Vincent Valdez and Ry Cooder, “El Chavez Ravine” (detail of hood and bumper), 2005–7, oil on 1953 Chevy Good Humor ice cream truck, collection of Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

In the above detail, one can see a man who looks like he is from the past (he is Ry Cooder) looking to the left. The person with the closely cropped hair is the artist himself. One fan to his right (with a brown arm) holds a giant “VIVA LA Dodgers” foam finger, which identifies him as a contemporary Latinx viewer (presumably with no memory of the area’s history). Fictively, the museum visitor is also one of the spectators at Dodger Stadium. But – like Valdez and like the ghosts of Chavez Ravine who inhabit the surface of this vehicle – we see far more than most fans.

Vincent Valdez and Ry Cooder, “Study for El Chavez Ravine,” partially painted toy truck, collection of the artist. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

The exhibition included a toy truck (on top of the black flat file), on which Valdez made some preliminary sketches. Over time, his treatment of the ball park became much more complex and sophisticated. On the body of the actual truck, Valdez is at his best when he is at his most surreal, when he brings together multiple realities and combines them with fantasy and/or nightmare. Other portions of the truck are less interesting.

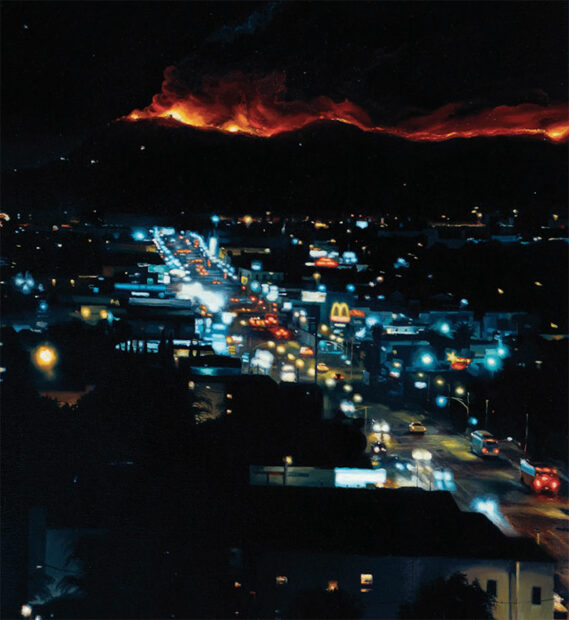

Vincent Valdez, “Burn, Baby Burn!” (detail of right panel, with view of Los Angeles hills on fire), collection of the artist. Photo: Elon Schoenholz, exhibition catalog, p. 204

In the “In Conversation Valdez/Cooder” video linked above, Valdez recalls sitting at a taco restaurant, watching a woman jog and a man walk his poodles, “and right behind, the entire time in broad daylight, the hills [are] on fire. I just remember thinking ‘this is not normal.’ Nowhere else would this be normal!”

He mentions Mike Davis’ book The City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles (1990), that, “in many ways, echoes what the future of America will become,” which, for Valdez, is part of L.A.’s appeal.

In Burn, Baby Burn!, Valdez has presented the hill fire in a nocturnal setting, where it dazzles like a flaming curtain on the mountainous perimeter of the city, a small taste of the dangers always lurking in the hills, which exploded in the horrific, uncontrollable fires that consumed so much of L.A. earlier this year.

Excerpts for John, 2012

Vincent Valdez, “Excerpts for John,” 2012, oil on canvas, set of six, collection of the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Excerpts for John is an homage to Valdez’s best friend Robert Holt, Jr. (1978-2009), who joined the military in order to attend college. Holt served as a combat medic in Iraq but suffered from PTSD and killed himself. The six paintings in this series “translate” the artist’s emotions on the cold, rainy day of his funeral.

Such a constrictive project – with so much white space and a severely restricted palette – is extremely self-limiting. It’s like Superman choosing to paint with a Kryptonite brush. I wish there were more parts to this story, such as six dream-like paintings of Holt imagining his career after college, and another set depicting the hellish experiences he encountered in Iraq (though he didn’t want to talk about these experiences). Were this the final set of a longer series, it would have more impact.

Valdez did a large portrait of Holt in action called John (2010-12, not in CAMH exhibition), which he donated to the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 2019. Wally films made a short film called Vincent Valdez: Excerpts for John (2012) that treats both John and Excerpts for John.

The Strangest Fruit, 2013

Installation view of “Vincent Valdez: Just a Dream…,” with “Eaten (In America)” left; “Goodbye Marianne” (on gray wall); and “The Strangest Fruit” (right). Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

In 2013, Valdez created a series whose title is inspired by the song Strange Fruit, which was made famous by Billie Holiday. The anti-lynching song was written by Abel Meeropol, a member of the Communist Party, in 1937. Its three verses are as follows:

Southern trees bear a strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

Pastoral scene of the gallant south

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth

Scent of magnolias, sweet and fresh

Then the sudden smell of burning flesh

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck

For the sun to rot, for the tree to drop

Here is a strange and bitter crop

The U.S. government, in particular Federal Bureau of Narcotics commissioner Harry Anslinger, persecuted Holiday simply for singing the anti-slavery song. Her cabaret license was revoked, and she was prevented from receiving medical attention, which led to her death (see: Liz Fields, “The story behind Billie Holiday’s ‘Strange Fruit,’” American Masters, PBS, April 12, 2021).

Whereas Meeropol’s song addresses the lynching of blacks, in this series, Valdez wanted to call attention to the much lesser-known lynching of Mexican Americans, particularly in Texas (see Nicholas Villanueva Jr., The Lynching of Mexicans in the Texas Borderlands, Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2017). At the same time, Valdez also wanted to comment on ongoing forms of oppression against Mexican Americans/Chicanos, Latinx, and people of color in general.

Therefore, Valdez had his models (which, as usual, were friends or family members) dress in contemporary clothes. He consulted with his models, and he showed them historic photographs of lynched black men, primarily from the book Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America (James Allen, ed., Santa Fe: Twin Palms, 1999), which were utilized as rough templates to give a sense of the appearance of lynched corpses.

Valdez explained this series in a 2013 lecture:

… metaphorically speaking, these dangling males are equivocal of both the past and the present. They symbolize the estimated thousands of brown bodies that have been erased throughout Texan and American history during the lynching era of the 1800s, and into the present. Most importantly, these portraits [also] represent the contemporary brown minority male, who continues to struggle free from the invisible noose in modern-day America (“The Strangest Fruit: A Symposium: Vincent Valdez,” Brown University, October 18, 2013).

In this 2013 lecture, Valdez listed contemporary, ongoing forms of oppression that constitute the “invisible noose:”

Oppressive methods and institutions, which are implemented to target and confine young males in society, such as mass incarceration, [for] profit prison systems, biased justice systems, defunded education, racial profiling, stereotyping, police brutalities, poverty, drug wars, military wars, assimilative measures, mass deportation, and immigration hysteria are just a few of the insurmountable measures that loomingly threaten young minority males at an early age.

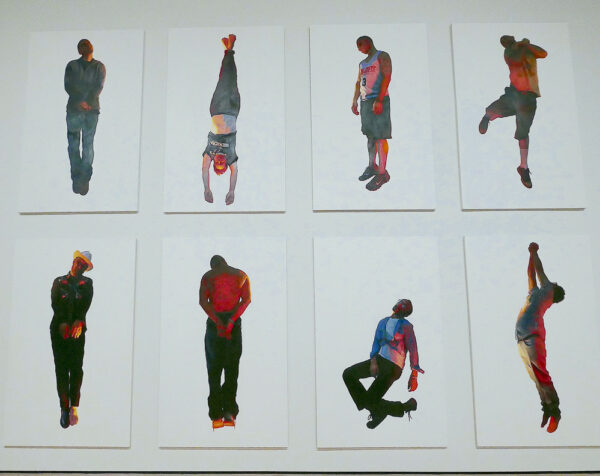

“Vincent Valdez: Just a Dream…,” installation view of “The Strangest Fruit.” Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Valdez also explained his rationale for isolating his figures, which stripped them of context. By eliminating the nooses, trees, white spectators (who often picnicked at lynchings, which had a celebratory, carnival atmosphere in the South), etc., he made the contorted bodies a site of singular focus. These bodies struggle, continues Valdez, not only to disentangle themselves from the physical noose, but also “the mental noose that is ever-present, and prevents them from ever becoming truly free.”

Valdez has blended the historical and the contemporary, and in so doing, he has endowed the lynching theme with a double meaning: on the one hand, literal historical lynching (the physical noose), and, on the other, oppressions that continue to this day (the mental noose). Moreover, he likens these lynched, floating, or resurrected men to the boxers, soldiers, and persecuted martyrs who are “struggling to become free, facing all odds.” Consequently, they are a continuation of his earlier themes.

Moreover, in these paintings, the stripping-down of subject matter to the forms of the solitary bodies produce deliberate ambiguity. It is for the viewer, says Valdez, “to decide whether these male bodies are descending or dangling from a tree… Or… doing quite the opposite… ascending into the heavens… being resurrected from the past once again.” Consequently, these bodies, which bear the marks of suffering and death, can also signify release, and a resurrection of sorts, in the form of release from the “mental noose.” Eliminating backgrounds also permitted Valdez to produce the series quickly. In a year’s time, he was able to complete a dozen canvases.

Ironically, in practice, Valdez found that he had to rely on physical nooses in order to make sufficiently compelling photographic studies for these paintings. All previous efforts had failed, until he not only tied the hands and feet of his models but also had assistants pull on nooses affixed around their living necks. Only the deployment and tightening of actual nooses enabled him “to capture” the characteristic contortions of the tongue, the bulging of the eyes, the spastic, desperate extensions of the fingers, and the precise, twisted facial expressions caused by asphyxiation. The physical nooses that had been so necessary in the studio were subsequently eliminated in his paintings. The colorful Texas skies that had dominated the backgrounds of so many of his paintings and pastels were projected onto the bodies themselves.

The City I & II, 2015-16

Vincent Valdez, “The City I & II,” 2015-16, oil on canvas, collection of the Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas at Austin. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Encountering Philip Guston’s The City (1969) at the Blanton Museum in Austin provided Valdez with the spark to make these two paintings. He made connections with other works of cultural commentary when he was driving home, especially Gil Scott-Heron’s song The Klan (1980). (Valdez dedicated these two paintings to Guston and Scott-Heron.) When Valdez got home, he began sketching men in Klu Klux Klan (KKK) robes (see “FAQs,” Vincent Valdez, The City, 2018, The Blanton Museum of Art, which includes an illustration of the Guston).

Below the surface, an encounter Valdez had with the KKK had been festering for years. When he was sixteen, Valdez inadvertently passed through police tape at the Alamo on his way home from work. Suddenly, he came face-to-face with a KKK Grand Dragon, whose headpiece revealed his face. What must have been a speedy stare-off seemed like an eternity to the artist. Valdez noticed men in white marching, and a group of counter-protesters, amid a considerable amount of shouting. He had stumbled upon a Klan rally, right at the Alamo. Valdez noticed a line of policemen (all black or brown) who had interposed themselves between the KKK and the counter-demonstrators. The experience made Valdez reflect on his place in his native city, and it engendered a sense of anomie. Valdez recalls having the feeling, for the first time in his life, that “I don’t belong here” (see “Maria Hinojosa & Vincent Valdez Conversation,” Vincent Valdez, The City, 2018, The Blanton Museum of Art).

Valdez’s setting for these two paintings is nonspecific, and the human encounter is imagined. As he explains: “This could be any city in America. These individuals could be any Americans. There is a false sense that these threats were, or are, contained at the peripheries of society and in small rural communities” (see “About the Art,” Vincent Valdez, The City, 2018, The Blanton Museum of Art).

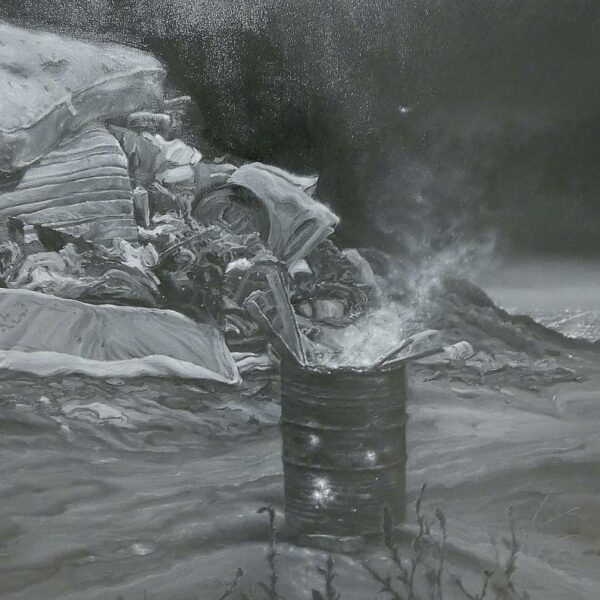

The black-and-white palette blurs the separation between documentary photography and art, and between time periods. The artist intended to create a degree of confusion and instability, and thereby to bind past and present, as he did in The Strangest Fruit. This vision of the KKK and of the garbage heap (the latter is the subject of The City II) is a cumulative, totalizing indictment of U.S. history. “The image is twenty-first century America,” explains Valdez, “but it also reveals all of the previous American centuries before it” (“FAQs”).

Valdez has always been critical of the naive assertion that Barack Obama’s election to the presidency demonstrated that the U.S. had become a “post-racial society,” and The City I constitutes “push-back” against that view. Instead, Valdez views racism and inequality as national constants, as American as apple pie. In fact, on these shores, they were firmly established as national traits before apple pie became a national symbol, because, as the expression goes, racism and white supremacy were baked into the Constitution.

Valdez enumerates the possible roles and professions of the KKK members: “It is possible that they are city politicians, police chiefs, parents, neighbors, community leaders, academics, church members, business owners, etcetera. This is the most frightening aspect of it all” (“About the Art”). Historically, civic leaders and authorities were at the center of Klan activities, which is why they were able to terrorize and murder with impunity.

Today, if anything, white supremacists (though no known KKK members) are likely to have higher positions within the Trump administration than they have enjoyed on the national scene in a century or more.

In Valdez’s fictive scenario, the KKK members are in the process of assembling. They have not yet commenced their secret rituals. Essentially replaying Valdez’s encounter at the Alamo, the visitor to the museum looks at the Klanspeople (Valdez has pointedly included women and a child), and they in turn look at the visitor who stands before them.

Vincent Valdez, “The City I” (detail of group on the right), 2015-16, oil on canvas, collection of the Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas at Austin. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

The city in the background signifies that these people are urban, rather than rural. A number of consumer articles demonstrate that they are educated and prosperous, as well as urban. They are likely to hold high posts in society. Several of these figures sport class rings. They are educated and proud of it. Alumni who wear such rings take part in higher education networks to better their station in life. The women’s hands are manicured, and their curly, light tresses are as carefully groomed as the hair on a Botticelli Venus. Watches and jewelry also signify affluence. One man checks his iPhone while a late model Chevy truck serves as the primary source of illumination. Whereas lighting in traditional religious paintings often emanates from a sacred source, the light in this painting is neither supernatural nor holy. One beam of light from the truck even seems to join with light emanating from a torch held by a man on the far left. Artificial industrial light thus merges with pre-industrial light – the latter often utilized to enable mob violence.

Valdez associates Chevrolet with a commercial the corporation ran from 1985 to 1993, when it billed itself as “the heartbeat of America.” It’s an Everyman’s truck, sold as the essence of America, just as the beer one Klansman drinks is Budweiser, an Everyman’s beer, not a fancy import like Heineken. In fact, this particular can bears the motto “America is in your hands” (Hinojosa/Valdez Conversation). Budweiser even temporarily rebranded itself as “America” because, according to the PR firm’s rationale: “We thought nothing was more iconic than Budweiser and nothing was more iconic than America” (see: Tiney Ricciardi, “Budweiser rebranding as ‘America,’ throwing every patriotic slogan that fits on label,” The Dallas Morning News, May 10, 2016). Consequently, this beer and this truck are highly suitable products for right-wing, red-blooded nativists who believe they are the essence of this nation, and no one else really belongs here.

Vincent Valdez, “The City I” (detail of group on the left), 2015-16, oil on canvas, collection of the Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas at Austin. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

On a more sinister level, Valdez notes that the Chevrolet truck bears a cross emblem on its grill. This flattened cross logo calls to mind the burning crosses utilized in KKK rituals (more about that below), as well as the cross on the center of the facepiece belonging to the man’s hood in the detail above. Budweiser is a German name, and a more sinister association is made when the man with the beer raises his other hand in a manner that some have associated with a Nazi salute. The Budweiser man’s hand is thrust between two hooded heads, and it appears over the head of the child. Valdez made the gesture somewhat ambiguous. The man does not stand stiffly at attention, and he does not use his right arm, as is proper for a Nazi salute. Valdez observes that the man could be saluting or waving. In any case, the Klan salute, made with the left arm, originated in 1915.

Anyone following the news is aware of the controversial salutes made by Republican operatives Elon Musk (as this review goes to press, Donald J. Trump and its lawyers have, at different times, contradictorily asserted that Musk both is and is not the head of DOGE, and that DOGE both is and is not a genuine federal agency) and Steve Bannon (an agent who is now out in the cold in Trump World, but endeavoring to assume a significant position). Accusations that Musk twice made a Nazi salute (he stood stiffly, and used his right arm) were countered by claims that it was a “Roman” salute. There is no record of an ancient Roman salute of this nature. The gesture apparently originated in The Oath of the Horatii (1784), by the French Neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David. The only Romans to actually make such a salute were, in fact modern-day fascists. After Italian fascists utilized the salute, it was adopted by the Nazis. In some circles, Bannon (who also made a stiff, right arm salute) was mocked for imitatively playing a hapless Mussolini to Musk’s Hitler.

As Valdez has it, the Klan assembly is meant as a “painful” revelation of that which is normally repressed and hidden, but which is nonetheless “the truth.” The baby – like the other Klanspeople – is a child of affluence, with his own well-tailored Klan uniform, a Pikachu doll, and child’s Nikes – likely Air Jordans, says Valdez (Hinojosa/Valdez Conversation). Famously, Michael Jordan refused to endorse political candidates or take a stand on racial issues, once declaring: “Republicans buy sneakers, too.”

The baby is the only figure Valdez hesitated to depict in The City I. He knew that it would likely upset and dismay audience members inculcated in “the purity and innocence of childhood.” Valdez concluded that the baby’s inclusion would be instructive, because “no one is born to be violent.” Racism, says Valdez, is taught and even “recycled.” Valdez likens the child’s pointing gesture to that of Uncle Sam in Kill the Pachuco Bastards! (Hinojosa/Valdez Conversation). Consequently, the child’s gesture can be seen as an accusation, or as a gesture of exclusion.

As an art historian, I associated the KKK child within this assembly with the genre known as the Sacra Conversazione (Sacred Conversation), rendered by countless Renaissance and Baroque artists. In these paintings, the Holy Family is surrounded by symbolic, casually posed saints. Because they inhabited different locales and time periods, they are often isolated and absorbed in their own thoughts. The Christ child often makes a gesture, sometimes significant, such as foretelling his passion by accidentally poking his finger with a thorn, etc.

Valdez has created a wholly malevolent Conversazione. I imagine most art historians – and no doubt many horror film aficionados – would be particularly attentive to this child, who has imbibed racial hatred along with his mother’s milk. Instead of a merciful messiah, this child is more likely destined to become some kind of monster. With miraculously malevolent foresight, this child could already be fingering a future victim: the one that stands before this canvas in a museum.

Other artists have also depicted Klan-robed children to powerful effect, such as Paul Rucker. His Storm in a Time of Shelter (2015) features three children in KKK robes before a charred cross bearing the titles of hymns. Some, like “The Old Rugged Cross,” had also been sung by the Klan. Characterizing his exhibition, titled “Rewind,” at the Baltimore Museum of Art, Rucker declared: “This show is about American history repeating itself over and over again” (see: Katherine Brooks, “Artist Paul Rucker Is Taking Back The Racist Symbols Of America’s Past,” Huffpost, October 2, 2015, updated August 15, 2017).

Vincent Valdez, “The City II” (detail of right-center), 2016, oil on canvas, collection of the Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas at Austin. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

The City II is fundamentally about the haves and the have-nots. The refuse, in a symbolic, non-literal manner, represents what Valdez calls “the left behind” (Hinojosa/Valdez Conversation). This garbage-filled, toxic landscape with a literal trash fire (in a can riddled with glowing bullet holes) stands in contrast to the shining city in the distance.

One can make a parallel between the garbage in The City II and the couple in Expulsion From the Great City. Read in a less literal manner, the couple in Expulsion has been excluded from what we might call the good life. They, like the symbolic garbage heap in The City II, may simply be denied the chief benefits of urban prosperity. The couple might even inhabit the city, but be barred from the best of what it has to offer. Many of Valdez’s works are in dialogue with one another, and insights from one work can broaden our interpretation of another.

Returning to The City I, Valdez avoided making “another sinister portrait” of the Klan, one that would emphasize its power to dominate and terrorize. His intention, instead, “was… to strip them of their disguises, without literally doing so.” Rather than a physical unmasking, Valdez’s aim was to demystify the KKK by depicting their ordinariness (including their predictable brand preferences). Philosopher Hannah Arendt’s expression “the banality of evil” (utilized in her 1963 book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil) is relevant here, because it does not take great people to commit evil, nor to lead others to commit great evils. Valdez did not want to aggrandize the Klan in any manner. Notwithstanding its monumental scale, its aim is “to strip them [the KKK] of their power” (“FAQs”).

To this end, Valdez was careful to avoid glamorizing, aestheticizing, or validating the Klan. Those functions had been performed to monumental effect by D. W. Griffith, whose Birth of a Nation (1915) led to the rebirth of the defunct organization. On the film’s opening night in Atlanta, Joseph Simmons, the founder of the modern Klan,

and fellow Klansmen dressed in white sheets and Confederate uniforms paraded down Peachtree Street with hooded horses, firing rifle salutes in front of the theater. The effect was powerful, and screenings in more cities echoed the display, including movie ushers donning white sheets. Klansmen also handed out KKK literature before and after screenings (Alexis Clark, “How ‘The Birth of a Nation’ Revived the Ku Klux Klan,” History, August 14, 2018, updated August 10, 2023).

The film featured derogatory stereotypes, including the central trope of rapacious black men imperiling innocent, white women (thwarted only by the KKK on horseback). Birth of a Nation was screened at the White House by President Woodrow Wilson (who re-segregated the federal workforce), and it was enthusiastically received in nearly every part of the country, ultimately helping to swell the membership of the Klan into the millions in just a few years.

Griffith’s film also inspired the iconography of the modern Klan, including the exclusive use of white robes and hoods (the First Klan had sported a motley assortment of robes, as well as horns, wizard caps, etc.) and the burning of crosses (taken from Scottish ritual, utilized in the book on which the film is based). Griffith introduced cross-burning in the most inflammatory manner: a virtuous white woman leaps off a cliff rather than succumb to the advances of a black suitor, becoming, in the ideology of the film, a martyr for her race. The Klansmen – in sacramental fashion – dutifully consecrate a cross in her blood before burning it, prior to lynching the black man who had pursued her.

The Birth of a Nation, the first blockbuster film and a founding monument of classical Hollywood cinema, had such a potent effect on its viewers that its fictive Klan became a real one. The flaming crosses, white robes, lynchings, and mob violence leaped from the screen into the street. Desmond Ang has demonstrated a dramatic spike in lynchings, mob violence, and KKK chapter formations in counties where Birth of a Nation was screened. Moreover, a century later, counties that had hosted The Birth of a Nation roadshows (the film toured with companies that brought special projectors and a full orchestra from 1915 to 1919) continue to exhibit significantly higher than average incidences of hate groups and hate crimes (“The Birth of a Nation: Media and Racial Hate,” Scholars at Harvard, July 22, 2022).

The Klan’s constitution of 1916, just a year after The Birth of a Nation, reflected values expressed in the film, including:

… to practice an honorable clanishness toward each other; to exemplify a practical benevolence; to shield the sanctity of the home and the chastity of womanhood; to maintain white supremacy; to teach and faithfully inculcate a high spiritual philosophy through an exalted ritualism, and by a practical devotedness to conserve, protect and maintain the distinctive institution, rights and privileges, principles and ideals of a pure Americanism (see: Chelsea Sutton, “Klan Records: Wayne County KKK Records Paint Picture of Klan Life in 1920s Indiana and Offer Data about Our Ancestors,” The Hoosier Genealogist: Connections, vol. 55, no. 1).

Also, see the Klansman statuette with the detachable, saluting arm that Sutton reproduces (when extended, the saluting arm means only KKK members and sympathizers are present). Simmons also repeated the KKK goals enumerated above in his pamphlet called ABC of the Invisible Empire, published in Atlanta in 1917.

I have made this detour through Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation to underscore the point that – sometimes, at least – art can really matter. Furthermore, in the last half-century of our nation’s history, art has perhaps never mattered more than it does now. Rights that many had taken for granted for decades are being swept away, and racism and inequality are on the rise. Ang notes the explosion of “extremist ideologies” that began as “obscure online forums” and traveled to “mainstream news outlets and ultimately the highest levels of government” (“Media and Racial Hate,” p. 33). Already in 2018, Valdez had noticed such a higher degree of open racism that he declared: “The [KKK] hood is not even necessary anymore” (Hinojosa/Valdez Conversation).

Dream Baby, Dream, 2018

Installation view of “Vincent Valdez: Just a Dream…,” with “The City II” and part of “The City I” (left); “The New Americans, #2 (Mr. Checkpoint)” (center); and “Dream, Baby Dream” (right). Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

As Valdez was completing The City I, Muhammed Ali died. Valdez watched the funeral services on television, which inspired him to create another series, based solely on the late boxer’s eulogists. He was impressed by their racial, gender, and religious diversity, which accorded with his vision of America.

Installation view of “Vincent Valdez: Just a Dream…,” with “Dream, Baby Dream.” Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

The Dream, Baby Dream series is laid out in a grid, based on the opening section of The Brady Bunch television show, which Valdez watched as a child. Speaking of that program, Valdez concluded: “I don’t look like the Brady Bunch. And that family’s not like my family” (Hinojosa/Valdez Conversation). The grid isn’t just a structuring device. By replicating it while replacing the figures, Valdez has replaced a non-diverse past with a diverse present, one that hopefully points to a diverse future.

Vincent Valdez, “Dream, Baby Dream (2),” oil on paper, courtesy of the artist.” Photo: Vincent Valdez website

Ali’s eulogists are all depicted in the same moment, an instant before speech. Grief is expressed by their faces, while they are gathering up strength and are as of yet unable to articulate words. Art is mute (for the most part). Ancient artists utilized a hand over the face to express inexplicable sorrow, when words fail, and the mourner can neither speak nor look.

With multiple figures engrossed in grave silence, Valdez has portrayed a gathering storm of grief. Moreover, the expressions of these various people better convey enormous sorrow than would a speaking likeness.

In terms of style, the Dream, Baby Dream paintings are much more painterly and exhibit considerably more chiaroscuro than The City I. Part of the reason may be that Valdez wanted to give reportorial and photographic clarity to the Klan grouping, and it was natural to shroud Ali’s mourners in darkness. But I think he also wanted to depict the KKK at a certain formal distance, with a high degree of matter-of-factness. This difference in handling is a way of denying agency to the KKK. Valdez clearly did not want to make the Klan beautiful, as the Dream, Baby Dream paintings are beautiful, in their own tragic manner.

Compare The City I and The City II, and you will see that Valdez painted the garbage and the burning trash can in a more beautiful manner than the Klanspeople. He uses more light/dark contrast, which is visually exciting. The garbage also has more texture, more three-dimensional highlights, and more gestures done with impastoed brush strokes. By comparison, the Klanspeople – except for the ones on the edges, which have some dramatic backlighting – are rendered in relatively bland half-tones.

Returning to Ali, though he was stripped of his title and (for a time) banned from boxing because he was a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, he went on to become one of the most outspoken, intelligent, funny, and effective critics of U.S. hypocrisy. In the end, he was one of the most beloved and respected men in the world. In 2024, Michael Jordan, who pointedly did not want to be seen as a role model, had an estimated net worth of $3.2 billion. Who was the richer man?

Eaten, 2018-19

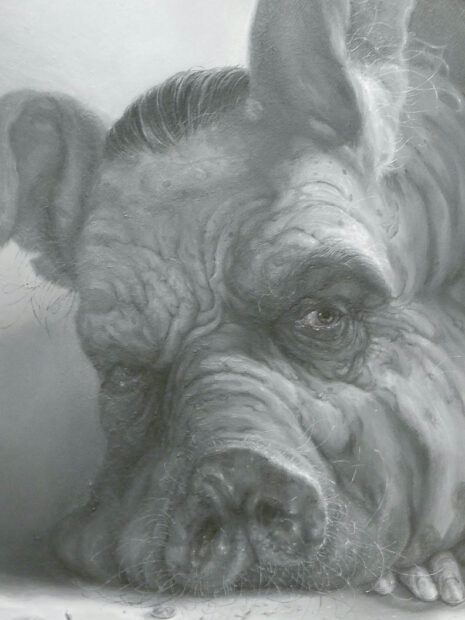

Vincent Valdez, “Eaten (In America),” 2018-19, oil on canvas and bronze installation, collection of David Hoberman, promised gift to the Hammer Museum. Photo: Vincent Valdez website

A corpulent, fully gorged mutant pig rests, after having devoured most of a suit-wearing man, and having taken a big bite out of a book for good measure. This greedy, hybrid porker bears the features of several unsavory political figures. It’s vigilant, human-like eyes (recall the old man’s dog-like eyes in Remembering) are based on J. Edgar Hoover, who headed the FBI for nearly 50 years, during which time he built up such a formidable power base (and political blackmail enterprise based on illegal surveillance) that a succession of presidents feared his reach. Valdez refers to Hoover as “the godfather… of the surveillance state” (Vincent Valdez, “Vincent Valdez 2024 Pepper Distinguished Visiting Artist & Scholar Lecture,” October 24, 2024, Pitzer College Art Galleries, Claremont). A virulent anti-Communist, Hoover’s actions also earned him a portrait in Valdez’s El Chavez Ravine.

Vincent Valdez, “Eaten (In America)” (detail of head), 2018-19, oil on canvas and bronze installation, collection of David Hoberman, promised gift to the Hammer Museum. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Robert S. McNamara supplied the slicked-back human hair (not the ears, as incorrectly noted in the catalog) atop the pig’s head. He was this nation’s longest-serving Secretary of Defense, under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, until his 1968 resignation. McNamara oversaw the Vietnam War, when Cold Warriors subscribed to the “domino theory” (which held that a Communist victory in Vietnam would lead, like a vast chain of toppling dominoes, to Communist regimes around the world) and were eager to display American might. McNamara’s expansion of the conflict, which was unwinnable in the manner in which it was waged, resulted in untold suffering and death. It also necessitated the draft, which ensnared Valdez’s father.

Steve Bannon, noted above for his recent, controversial salute, was a former head of Breitbart News, which he took in a more rightist, more nativist direction. He was also a board member of Cambridge Analytica, where he was involved with the collection of Facebook data that was utilized in the 2016 election. Bannon was an advisor to President Trump during his first term, which is when this canvas was painted. He received a pardon (for profiting from his We Build the Wall scheme) on Trump’s last day in office. Unlike Musk, Bannon is opposed to the utilization of the H-1B temporary visa by foreign tech workers. Bannon’s fleshy, age-spotted and freckled face inspired the treatment of the skin on the pig’s head.

Lisa Duggin gave this memorable description of Bannon’s face in 2021:

There’s something uncanny about Steve Bannon’s face… He exudes a kind of ravaged resentment… He looks alcoholic and desiccated, unable to acknowledge his ultimate defeat, steeled by a doomed determination… He also looks uncannily like a debilitated witness and bellwether for the fall of U.S. empire, the collapse of global neoliberal centrism, and the persistence of a destructive nostalgia for past glory on the political right. Steve Bannon haunts the contemporary political landscape in ghostlike fashion — as both a sad fantasy of a lost world and an ominous threat (“Steve Bannon’s Face,” 2021, Commie Pinko Queer, Substack.)

Eaten has a strong retro quality (Duggan argues that even Bannon’s face has a retro quality). I imagined the (mostly) eaten man as someone destroyed (consumed) during the 1950s Red Scare.

Valdez offers a broader, all-consuming reading of this creature, one that indicts society, and potentially the individual viewer of it, as well:

Has this creature greedily devoured everyone and everything on its path, with no end in sight? Or, perhaps, are we staring into a mirror? A metamorphosis – confronting a deformed, unrecognizable version of our own systemic society. First, they get the others. Then, they get their own. Eventually, they eat each other. Until finally, they devour themselves (from “Just a Dream…” exhibition text).

When he made this work, Valdez took inspiration from George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945), but “mutated” and “regurgitated” through a potential Kafkaesque metamorphosis into something “brand new.” Thus, the nature of the creature is open to question. Valdez asks: “Have we become unrecognizable to our own selves… as empire, as nation, as people, as species?” Ultimately, Valdez challenges viewers to make their own interpretations of this work: “all of these hidden sort of symbols are for you to start to put together” (Pepper lecture).

The New Americans, 2021-ongoing

Installation view of “Vincent Valdez: Just a Dream…,” with “Made Men” (left), “The New Americans, #3 (Juan)” (center); part of “The City I” (rear); and part of “Dream, Baby Dream” (right). Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

In order to acknowledge positive contributors to society, in 2021, Valdez resolved to paint 21 monumental portraits of individuals who are “fighting the good fight” in the twenty-first century. Recognizing them as the underdogs fighting against a rigged system, Valdez characterizes these cultural warriors as “a stubborn pulse in a dying heartbeat” (“Tuesday Evening” lecture).

The two completed portraits included in “Just a Dream…,” both of which date from 2021, feature Juan Cartagena and Mr. Checkpoint. The former is active in LatinoJustice PRLDEF (the successor to the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund). He is a Civil Rights attorney who specializes in Puerto Rican and Latino rights issues, including immigrant rights, voting rights, criminal justice reform, economic justice, and mass incarceration.

Mr. Checkpoint is the founder of AFTP. The acronym, which is printed on the cap he wears in the painting, has a dual significance: it stands for “Always Film the Police,” and “Always for the People.” According to the AFTP, “we’re on a mission to bring transparency and accountability to law enforcement”

“The New Americans, #2 (Mr. Checkpoint)” (detail), 2021, oil on canvas, collection of Beth Rudin deWoody. Photo: Vincent Valdez website

Valdez has his subjects choose the settings in which he portrays them. Cartagena chose a small street where he opened his first law office. Mr. Checkpoint selected an intersection in Santa Monica, where a policeman, after stopping him for an illegal turn, arrested him for refusing a sobriety test. Mr. Checkpoint won the ensuing court case because he recorded the stop on the phone app he had created (see: Ashley Archibald, “Mr. Checkpoint goes to court,” Santa Monica Daily Press, May 23, 2013). Mr. Checkpoint also subsequently won a monetary judgment in connection with this arrest.

Key details of the case are referenced in Valdez’s painting, including an arrow pointing to the traffic light and No Turn sign, the police car with a flashing red light, Mr. Checkpoint’s hat and phone, and Mr. Checkpoint’s dogs, which were taken to the pound when he was arrested. The helicopters that fly overhead additionally imply other layers of surveillance. They are countered by the communications tower on the right, which enables cell phones and internet communications.

These monumental portraits stand close to eight feet tall. Valdez utilized a highly painterly technique in his depiction of Cartagena, which is rather dark, with a considerable amount of impasto. Mr. Checkpoint, on the other hand, was painted with a higher degree of clarity, smoothness of technique, and narrative exposition, in keeping with the theme of documentation.

Supreme, 2022-ongoing

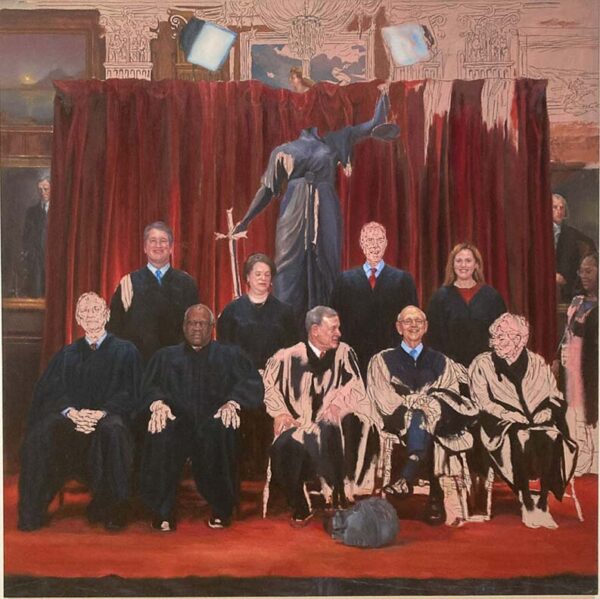

“Supreme,” 2024 state (ongoing), oil on canvas, courtesy of the artist. Photo: courtesy of Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, 2024. Photo: Peter Molick

For the first time in his career, Valdez felt a painting was so important and so topical that he exhibited it when it was far from finished. He began Supreme in March of 2022, on the day that Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court decision that guaranteed the right to abortion, was overturned. Roe had been decided in 1973 (see: “Roe v. Wade,” Center for Reproductive Rights), and it had been reaffirmed in other court rulings.