Each spring semester, Texas Christian University (TCU) presents an exhibition of works by its second year MFA candidates. Aside from being an opportunity to showcase the newest projects made by students halfway through the program, the candidacy show also validates that these artists have been approved to move forward in the program and are on track to receive their degrees next spring. This year’s exhibition, titled Refract, presents works by Mckee Frazior, Austin Lewis, Elijah Ruhala, and Raul Rodriguez (who, disclosure, is a longtime photographer friend and colleague). It is notable that it is the first time in recent memory that the MFA program cohort features all male artists. Beyond the title’s theme of distortion, a first glance across the artists’ bodies of work also points to a connection related to the use of construction materials and ideas related to labor.

Walking into the gallery, I was immediately drawn to Ruhala’s installation The(ir) Art of Loving, an environment built of thin wood strips and wax paper, all held together precariously by glue. The heart of the installation is reminiscent of a stripped-down bathroom with two vanities that face each other. Extending out from that main center are wooden components that visually expand the space into the gallery. These nooks and crannies are filled with M.C. Escher-like small staircases leading in various directions. Wax paper, most of which is painted with portraits, figures, and other imagery, is used sparingly but effectively.

Stepping into the small space felt like a trip into someone else’s memory. And while the section that includes the vanities was clearly the focal point, my eyes wandered around to the smaller niches throughout the installation. These microcosms reminded me of the multidimensional environment in the movie Interstellar, where the main character, Cooper, has access to years of moments and memories related to one specific room. The exact narrative of the work is mysterious, but it is apparent that the work is imbued with love, intimacy, and introspection.

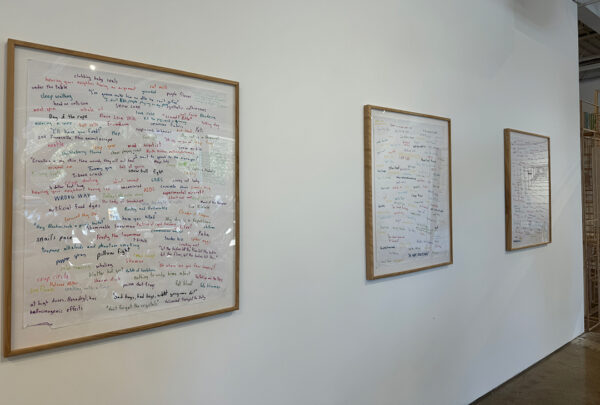

Taking up most of the front half of the gallery is a large, ambitious sculpture by Lewis. The lanky, organic form is made of an array of trash (cardboard, styrofoam, discarded lumber, mattress foam) that has been wrapped tightly with plastic and tape; it looks like something that crawled out of Stranger Things’ The Upside Down. Though the form mimics a spider-like or tentacled monster, the sculpture’s colors remain true to the source material, a mixture of neutrals along with yellows, greens, blues, and purples. These brighter colors are echoed in three framed text works hanging on a nearby wall. The text pieces, like the sculpture, pull from everyday life. They feature dozens of phrases like “head on collision,” “crop dusting,” “crazy cat lady,” “freemason,” and “meth lab explosion.”

While the connection between sourcing materials was clearly made, I couldn’t help but want something more from the visual component of the text works. The words are scrawled in a haphazard way. They would have been more compelling had Lewis composed the words in a more visually interesting or purposeful manner, perhaps even in a way that reflected the organic form of the sculpture, which easily drew attention away from the text. I walked around and through the sculpture, investigating its materials and enjoying the cutaway pieces that revealed the inside of its various arms.

Along the side wall of the gallery, connecting the front and back halves of the space, is Rodriguez’s photo installation Braceros. The series highlights the artist’s skill as a professional photographer while pushing the boundaries of how photographs are traditionally presented in art spaces. A mix of framed portraits, photos of ephemera, landscapes printed on vinyl adhesive, and images of figures laser etched into white fabric, hang across the wall, sometimes layered and overlapping and other times standing alone. Together the arrangement explores various components of The Bracero Program, a U.S. Government-sponsored initiative that brought Mexican farm and railroad workers into the U.S. from 1942 to 1964.

The large black and white photographs, some on vinyl adhered directly to the wall and others framed more traditionally, are modern-day photographs of places in West Texas related to the program. Men who participated in the Bracero program earlier in their lives are pictured in framed color portraits. Other images show government documents and items related to the program. Perhaps most interesting are the etched images of Bracero workers relaxing. For these pieces, Rodriguez isolated images from archival photographs and etched them onto white fabric, in a sense freeing the men from their labor and the land, bringing them into a plane of possibility. Rodriguez, who along with being a photographer runs Deep Red Press and is a zinemaker, is at heart a storyteller. In this installation he weaves together archival images, ephemera, and contemporary photographs to reveal untold narratives and connect the past and present.

In the back of the gallery, Frazior has created various interactive facets that consider the relationship between people and technology. TECH KNEE OHM consists of three main components. The first and most compelling is a set of three podium-like stands, each with a panel of eight light switch-style buttons that, when sequenced in various orders, present a different word projected on the wall in front of the podium. As I played with the switches’ many arrangements of “on” and “off,” I was intrigued by the various words that arose: fixed, exchange, stuff, loop, inside, anxiety, return, transparency, abs. I wondered where the words were sourced from and felt a sense of accomplishment once I was able arrange the switches at each podium to produce a good three-word combination. That accomplishment was quickly squashed when I realized that the words began to, without any action on my part, shift again after I set them. I struggled to regenerate my words, only to have them disappear again. Though I did have some amount of control, after a certain time had passed the computer took back over.

I stepped into a small enclosed space, constructed (like the podiums) out of plywood. The wires and tubes flowing into and out of the top and back of the space were playful, much like Lewis’ spidery sculpture. In the enclosed area was a screen with a plywood tabletop, which had push buttons on each side, similar to a pinball machine. The screen was pulling images from a camera placed inside the space, as well as from cameras on each of the podiums. Pressing the buttons in different combinations seemed to generate varying effects and pull images from different feeds; kaleidoscopic shapes swirled across the screen. Though incredibly different visually, the connection between this component and the podiums was evident: both works played with competing inputs and the struggle for control between people and machines.

The final component of TECH KNEE OHM was a printed grid with two axes: a horizontal axis with “machine” on the left and “human” on the right, and a vertical axis with “autonomy” at the top and “dependent” on the bottom. Gallery visitors are invited to take a sticker, either one labeled “human learning machine” or “machine learning human” and place it on the grid. The instructions note that stickers can be placed “on your person… on the framed image to your right [the grid]… [or] on any wood or plastic wrapped surface [in the installation].” Most people placed their stickers on the grid, though it was unclear to me what they were saying with their sticker placement. Were they speaking about where they personally fell on the grid? Did they have something else in mind that they were categorizing? As an educator, I am always intrigued by interactive works, especially those that gather information or data of some sort from participants, but I’m not exactly sure what this data is telling us about our relationship to machines. Perhaps rather than giving us a clear-cut answer, it asks us to question where we fall on this spectrum, how dependent we are on humans as compared to machines, and what we value — autonomy or dependence.

Refract is on view at Fort Worth Contemporary Arts through February 17, 2024.