Art is Short for ARTifact was a one-night-only pop-up group exhibition on November 3, 2023, at the Flower Shop Art Residency in Brownsville. The show was the result of Flower Shop Studio’s inaugural artists-in-residence program, which welcomed a cohort of four artists: Emily “Melly” Hinojosa and Leslie Ann Barrientos from Brownsville, Gil Rocha from Laredo, and Ray Madrigal from Sacramento. Despite their distinctive artistic styles and perspectives, seeing their installations displayed in a single space revealed elements of similar experiences and paired contrasts. Every artist appeared to initiate a conversation about the self — be that the shadow self, the past self, or the current and future self — and demonstrated through their installations the impact that can be created through found and everyday objects. My experience of this exhibit was as much an experience of these concepts as it was an engagement with the work each artist created.

Emily “Melly” Hinojosa

Hinojosa’s installation was always in the periphery of my sight when I entered the studio space — the rusted barbed wire erupting from a child-sized bed with pink sheets was peeking back at me from the open arch of the room that housed it. As I finally found myself entering the space, my own gaze was returned by eyes belonging to several people, all anonymous, filling the screen of a Sharp CRT TV. Their voices filled the room and weighed heavily on the viewer as they told personal stories of love, violence, and addiction. Despite the anonymity the zoomed-in view granted the figures, their eyes revealed a spectrum of emotions that aided in pulling the viewer deeper into the experience. Although we may not know the specific name or face of the person corresponding to each voice, we recognize feelings, see truths, and see ourselves reflected in their irises.

To my right in the room was a bed paired with a nightstand, and to my left, an altar adorned with a black-eyed Virgen de Guadalupe. La Virgen is a spiritual icon, the mother, and is positioned as a pillar of femininity and virtue that all women should embody, regardless of their situation. But here, in Hinojosa’s interpretation, the figure’s black eye demonstrated the harmful consequences of Marianismo, an expectation to take every strike — literal and metaphorical — in silence. Bottles of Dos Equis Beer took their place among the ritualistic elements of the altar, alluding to alcohol’s own state of reverence in the culture, despite the harm its abuse can cause.

Hinojosa created a liminal space, one they stated was a snapshot of where their own inner child lives, and crafted a juxtaposition between these child-like elements and trauma.

Leslie Ann Barrientos

Barrientos walked me over to a collection of installations set up in the backyard of the studio; the chatter of everyone in attendance fell away, save for that of a small group that was gathered under the single lightbulb that illuminated the area. The installations, made of three altar-like paintings constructed from everyday objects — cinder blocks, fruit, and linen — sat just on the edge of the light. The three sets of four cinder blocks supported flat surfaces draped in linen and painted with the juices of different fruits. Placed on top of each of these surfaces were fragments of cinder blocks and fruits — either atop the fragments or directly on the linen; the watermelon and pomegranates were broken open to show the fruit inside. Each of the four installations also had a book placed on them, including a book of medicinal plants. In comparison with Hinojosa’s installation that confronted the self, Barrientos’ acted as a transition of this self, and “a laying down and honoring of the past self.”

Leslie Barrientos, “A Calling Beyond My Knowing…”, 2023, linen, acrylic paint, charcoal, berries, pomegranate, watermelon, jamaica water, saw dust, books, cement slab and cinder blocks, 36 x 60 x 24 inches

All five senses were stimulated the moment you sat and interacted with her work: the sense of sight was activated through the layering of objects, one on top of the other. The sense of touch was activated through the viewer’s inclination of wanting to feel the textures of each layer, from the rough surface of the cinder blocks to the smooth skin of the fruit and the glossy covers of each book adorning the flat tops. Even the sense of taste was present through the scraps left on a table in a previous room, that wafted through the breeze of the back door. The ritual of these objects coming together was a sensory experience that invited the viewer to be present, to participate and contemplate, and engage in their own curiosity.

Gil Rocha

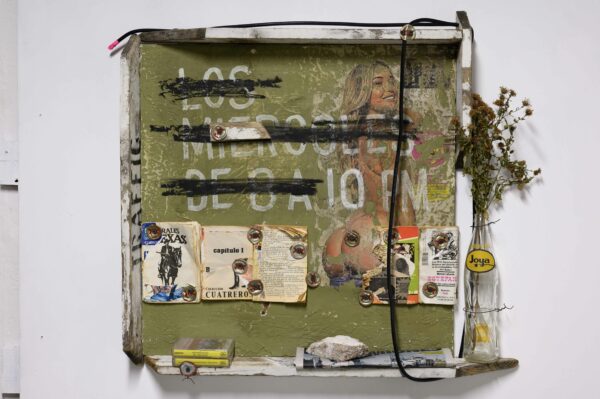

Rocha’s collection of assemblages and sculptures were placed throughout the exhibition space, and on a cursory glance the installations of found objects might’ve tricked the eye into thinking you had simply skimmed over windows and shelves with vibrant color. However, a more careful look revealed a pattern of non-traditional artworks playing with traditional technique.

There are shared elements across Rocha’s work — bottle caps from Dos Equis beers both pinned other objects in place and dotted the space; wires echoed the curves and loops of a brush, and wooden framing/paneling served as canvases. The use of these objects pointed to the artist’s influences of wabi-sabi and rasquachismo; both ideologies that allow for imperfection in art (and even welcome it), albeit through some differences in their aesthetic leanings. I thought this was most clear in the assemblage titled La Joya: wabi-sabi was present in the minimalist flower arrangement, and bled into rasquache with the use of a Joya soda bottle as the vase.

There was also a sense of nostalgia in Rocha’s use of these objects, which was carried through by the presence of ranchera music from a Los Dos Rancheros album on display, that had some song titles crossed out, and also through a working radio on what appeared to be the windowsill of an electronics shop. Nostalgia, though, is not without its counterpart. While rancheras, wires, and wooden home exteriors might evoke an upbringing in the late 70s and early 80s, these objects also carry with them the weight of a time when machismo and sexism were not fully investigated.

This is evident in the lyrics of rancheras, like those of Los Dos Rancheros, something the artist identifies as an emotional escape and a facade of perceived masculinity that belies a crying out for emotional introspection; this was emphasized by the two song titles that were not crossed out: “Trataré de Olvidar” and “Por Una Mujer Bonita.” Both of these focus on the suggested impact women have on the song’s singer, without introspection towards why the singer themselves feels a certain way. The depiction of women — pinup models included as transfers onto the wood of two of the pieces — put up a lens to these ideologies; it is something to be reckoned with as we think back to the male figures who had roles in raising us. Rocha, however, is aware of this fact and open to confronting it — he labeled these machista elements as a phase in both his art and himself. In fact, he presents the installations not as statements, but as questions of how the past parallels our present.

Just as Hinojosa and Barrientos explored concepts of the self and the ways in which we interact with these parts, Rocha claims to investigate the self as a byproduct of the male perspective — a perspective long influenced by machismo and an escape from (or rejection of) sitting with any emotion or sensibility perceived as weakness. In the words of the artist, this is “emotional rasquachismo,” or a dismissal of introspection as a survival tactic.

Ray Madrigal

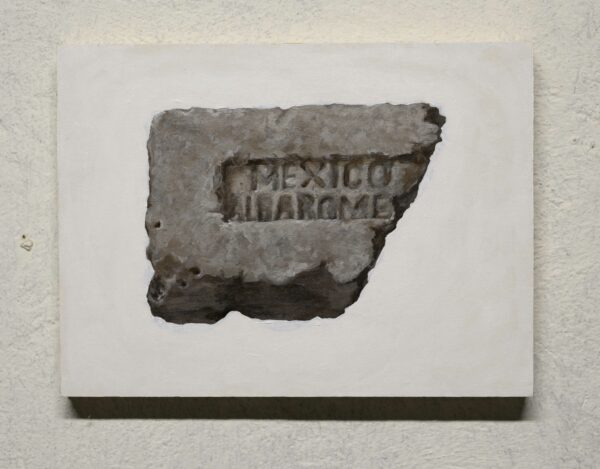

Survival is multifaceted, and not always about isolation and/or escape from the self. This is most clear within the contribution of Madrigal. The works are observations of everyday objects, such as an acrylic painting of a Mexican brick stamped with its company of origin’s name, and another of two candles, connected wick to wick, being lit by a single lighter. They exemplify how process and material — stolen office paper, borrowed graphite, and other materials, either at hand or procured — invite the viewer into a larger conversation about survival and the act of making.

According to the artist’s statement, the work is “a bid for Queer survival.” The work can be read not as an escape, but an invitation for those engaging with the art, participating in acts of making, to reinforce the existence of a safe space — somewhere where creativity flourishes and the true self is welcome to be explored. The capturing of everyday objects, and then the observation of their details, is an act of care and grounding.

Capturing the everyday holds the same value as capturing the abstract and ephemeral. It is in the everyday that we see ourselves, our hopes, wants, and shadows, reflected.

The Residency

All four artists, together with the public, came into the space to hold a conversation. Stepping into the main room of the studio was like witnessing a once-proverbial dialogue come to life, then engaging with it in media res. I witnessed several small groups enraptured in conversation as people flowed freely between installations — it was community in action.

Art is Short for ARTifact was on view at the Flower Shop Art Residency in Brownsville, Texas on November 3, 2023.