In the exhibition Denton Modernism, Photographs Do Not Bend Gallery (PDNB) foregrounds the superb artists of the Texas Bauhaus, most of whom were women. It is the sister show of the eponymic Texas Bauhaus, an equally remarkable and eye-opening exhibition of modern photography that PDNB hosted in spring 2022. The art in both exhibitions sets in relief a lost culture of Texas modernism created by a group of cosmopolitan women that clustered as educators and students around Texas State College for Women, now Texas Woman’s University (TWU), in Denton from the 1920s to 1970s.

With them they brought to North Texas a worldly knowledge of modern art gained from travels across America and Europe, and undergraduate and graduate course work in studio art and art education at an array of fine universities around the world, from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Fontainebleau to Hans Hoffman’s school in Provincetown. A common rite of passage for many was Columbia University’s Teachers College in New York City, where they worked with artist and designer Arthur Wesley Dow. Photographers Carlotta Corpron and Barbara Maples, painters Edith Brisac, Marjorie Baltzel, Marie Delleney, Dorothy (Toni) LaSelle, and Coreen Mary Spellman, jewelry-maker Thetis Aline Lemmon, and weaver Mabel Maxcy earned graduate diplomas there and then moved to Denton to live and teach.

While PDNB’s strength is photography, several lively paintings magnetize Denton Modernism. The flowers in Brisac’s painting, Calla Lilies (c. 1940s), body forth from the center of a canary yellow table.

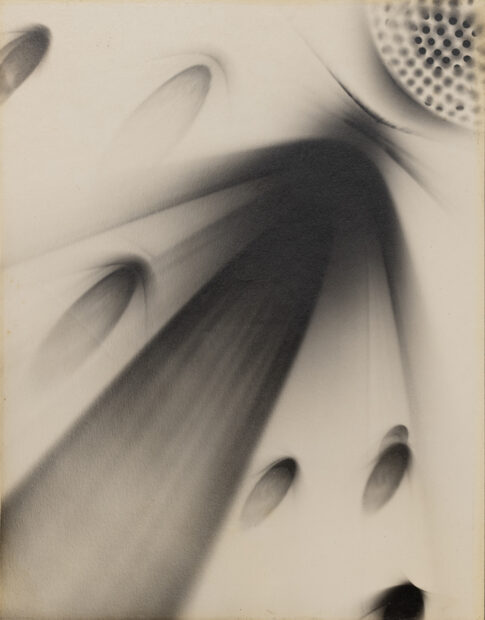

Its exaggerated, tipped-up perspective tilts representationalism from 1930s realism to spastic cartoon. The subtler black-and-white photographs of Clarence Tripp and Margaret Hicks adjacent to the painting mark a quiet counterpoint, especially Tripp’s Birth of Science (c. 1940s), which is a soft and milky close-up of floral form.

Its diagonal split, culminating in a bespeckled disk, suggests the interior space between two flower petals or human legs. Similarly restrained and ruminative, the abstraction of form in Hicks’ black and white untitled photographs from 1967 manifest in varied shapes, both curvy and rectilinear.

Beyond her photographs, it is the funky free-minded paintings of Hicks that take the show. They are bright, bold, and other-worldly — so many unpeopled hallucinogenic landscapes of science fictions to come. In Sunrise at the Lake (c. 1980s), Hicks inverts sky and ground, as orthogonal stems connect skyborne rivulets of red, green, and yellow above to galactic golden spheres floating in the putty-green water below.

In What A Trip (c. 1980s), a yellow tree trunk in the foreground gives way to ever-smaller receding ovals. The shapes strike a sense of synesthesia — sight and sound all at once — as the forms seem to echo into the background as if the o-o-o of doppler radar. Early Fall (1986) is a rhizomatic sectional cut-away of earthly undergrounds.

Root networks form below, yet nothing breaks ground atop. Neither modern nor postmodern, Hicks’ paintings are fission in action, their imagined spaces creating explosive chromatic liberation.

Behind the sexualized and eldritch abstractions of Tripp and Hicks course rich, layered biographies, similar to the ambitious scholarly resumés of the women listed above. Born in Denton in 1919, Clarence Arthur Tripp was a photographer-filmmaker who practiced psychology later in life. After graduating from Corsicana High School, he studied photography at the New York Institute of Photography, became a member of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, and worked at 20th Century Fox during WWII making wartime propaganda films. In the postwar period, Tripp became fascinated with Freudian psychology, earning a PhD in psychology from New York University. He worked at the Alfred Kinsey Institute for Sex Research and later penned The Homosexual Matrix (1975), a book that made same-sex relationships normal and healthy. Native Chicagoan Margaret K. Hicks, born in 1935, was similarly an open-minded citizen of the world. A two-time Fulbright scholar who made homes in South Africa, Beirut, and Lebanon, she ultimately settled in Denton. She taught at Navarro College in Corsicana, where she was Art Director from 1966-91. Hicks, an avid free-speech activist, marched at the age of 80 in 2015 on the Austin Capitol, picket sign in hand, in solidarity with Texas teachers.

Who would guess that such a sophisticated band of liberal artists lived in North Texas during the first half of the twentieth century? Who knew Texas modernism had a progressive streak oriented around sexuality and gender? Admittedly, calling the luminous, light-refracting experiments of Corpron, Hicks, Tripp, Ida Lansky, and Barbara Maples “progressive” is anachronistic, a projection back in time from the twenty-first century. To the artists, their work was neither political nor progressive. They likely shunned labels, with perhaps the exception of “modern.” While they broke new ground for feminist artists to come, it is highly unlikely the women would have considered themselves feminists. Their goal was to exploit the novel possibilities of photography as a technological medium of art. They were experimental artists teaching the “new vision” of modernism proffered by the Bauhaus, the design school that opened in Weimar, Germany between world wars. They sought to be artists, not women artists; modernists, not women modernists.

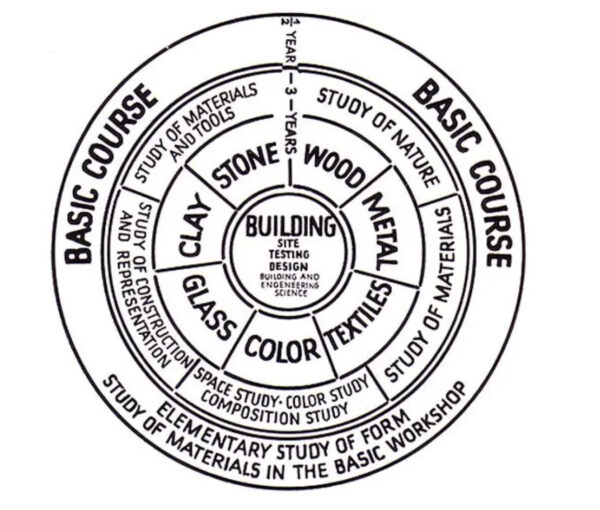

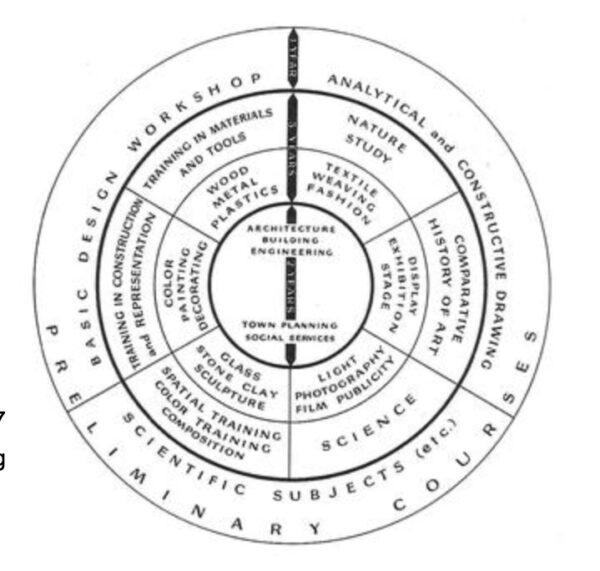

Corpron, Maples, Lansky, Hicks and the others nonetheless appear as future-oriented avant-gardists from a contemporary viewpoint. It is not simply because they were women who succeeded in a world even more dominated by the patriarchy than our own, but that they constructed systems of education and agency by which other women to come would succeed as well. The Bauhaus was another source of forward-looking utopianism, though not necessarily altogether politically progressive in the way we think today. The related identification “Texas Bauhaus” names the modern photography practices of Corpron, Lansky, and Maples, among others, that cascaded from the influences of two Hungarian Bauhaus figures, László Moholy-Nagy and György Kepes, during their short teaching stints in Texas in the early 1940s. Texas painter Toni LaSelle studied with Moholy-Nagy and Kepes in Chicago during the summers of 1942 and 1943. She also invited Moholy-Nagy to lecture in Denton in those years. Kepes then followed, teaching a semester at North Texas State University (today the University of North Texas) before leaving for Brooklyn University and then for an illustrious career at MIT. Without a doubt, the Bauhaus was a beacon of new design and art pedagogy, with its circular pedagogical wheel marking a radical departure from age-old hierarchical academic training.

But the failure of architect Walter Gropius, the inaugural director of the school, to fulfill the promise to matriculate women into the architecture workshop revealed patriarchy to be baked into the Bauhaus. Women nonetheless enrolled at the school. Denied access to architecture classes, they were relegated to the weaving workshop, where they designed textiles and wallpaper in patterns of geometric abstraction that they sold commercially. Monies earned by the women paid the bills for the school, since the architecture workshop headed by Gropius failed to do so.

This seems to be a problem that just won’t disappear, especially when considering the small number of women’s voices at the International Light Art Symposium in Budapest earlier this year (September 14-15, 2023), held in honor of Moholy-Nagy and Kepes. Leave it to Texas, the red-hot state now struggling its way to purple, to provide a platform for the women of Bauhaus modernism. The works in PDNB’s The Texas Bauhaus last spring and Denton Modernism currently on view elaborate the full gender- and sexuality-rich story of Bauhaus modernism by way of its rich tentacular diaspora into North Texas.

Denton Modernism: 1940-1980 is on view at PDNB Gallery in Dallas through October 7, 2023.

1 comment

There is a small error in your review of the PDNB exhibition. Kepes actually at what is now the University of North Texas for a full academic year. He was invited to teach there by Dr. Cora Stafford who was very well connected to the contemporary art world and to individuals like Alfred Barr the founding director of MOMA and a very good friend of Cora Stafford’s.