Claiming both Juárez, Chihuahua, Mexico, and El Paso as hometowns, Dallas-based artist Karla García visually explores border politics as well as her personal history with the desert landscape through ceramics and site-specific installations.

A founding member of the Nuestra Artist Collective based in Dallas, García holds a MFA in Ceramics and a Museum Education certificate from the University of North Texas. Her work has been featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions, including as part of the Nasher Sculpture Center’s Windows series in 2020. Over the last few years, she has also been selected for a variety of artist residencies and was awarded multiple project grants.

She and I recently discussed her work and process. She also shared about her forthcoming sculpture for the City of Fort Worth’s public art collection.

Caleb Bell (CB): In the exhibition Soy de Tejas in San Antonio, your installation La Línea Imaginaria is composed of ceramic sculptures resembling cacti in thoughtfully placed on a bed of sand. This piece is a continuation of your recent work, further exploring these sculptural forms and their presentation. What do these forms represent to you? What do you hope viewers take away for your piece?

Karla García (KG): I feel so grateful to be included in the Soy de Tejas: A Survey of Latinx Art, curated by Rigoberto Luna. I wanted to recreate La Línea Imaginaria, which was a binational project from 2022 that I displayed at my hometowns of Juárez, México, and El Paso, Texas. The opportunity to share this exhibition with other Latinx artists in Texas was exciting since we share the cactus symbol of our Mexican heritage. In my work, the cacti sculptures connect my cultural identity to the desert landscape of my hometowns — I claim both cities as a part of my upbringing. The way I like to describe this place is as a shared desert landscape divided by a wall with a shared history, along with people who commute back and forth. While there is no physical distance between each city, the cities are strikingly different. The culture, the language, and the connection to Mexican cultural history change, and yet our border identity is shared.

When I began making the landscape series in 2020, the cactus sculptures were a type of self-portrait. I left the imprint of my fingertips visible as I pinched the spines of the cacti, showing details that mimic when a plant shrivels then continues to grow. This imperfect form is a reflection of how the environment influences the growth of these plants, which is a tribute to our own resilience when coping with loss or hardship. The sculptures were left unfired as a way to directly reference the land. Each cactus is a reflection of my own history, representing a different emotion such as grief, love, resilience, and personal growth.

La Línea Imaginaria feels so important to me because it is no longer just my story. It is connected to anyone who has migrated and has a story to tell. The symbol of the cactus clearly speaks to Mexico’s culture and people. Its placement by the wall makes it emblematic of current border politics and immigration. In this installation, anyone that recognizes the cactus as symbolic can see themselves or understand the context. For people that are unfamiliar with this symbol, the landscape is a place we can all recognize and admire (or not), but the photos next to the installation allow us to enter the larger conversation about nature, cultural symbols, politics, and human rights.

CB: Can you expand on the ephemeral nature of those pieces, as opposed to your fired works?

KG: When I use unfired clay, it is about the materiality of clay being a type of soil — a malleable mud or dust depending on the piece I’m making. Although the unfired sculptures are physically fragile compared to ceramic objects, I am thinking about how land is organic and filled with creatures and root systems of the plants we see in nature. In this case, the cacti coexist with the land, which itself is political, humble, extraordinary, and will definitely outlast us. My ceramic pieces are connected to the concept of healing, which is tied to having a supportive community.

As you know, the history of ceramics is about community and survival. For thousands of years, ceramic objects functioned as vessels to carry water or food. They were also sculptural objects like fertility figures or deities that were carried along or placed in homes or places of worship. So when I fire the cactus pieces, it allows me to see my works in a new light. I appreciate the past and every experience that has led me to where I am now, and I am excited to continue exploring how clay, history, and philosophy continue to inform my work.

CB: I know you create clay drawings as well. Can you describe those and how they relate to your sculptural works and installations?

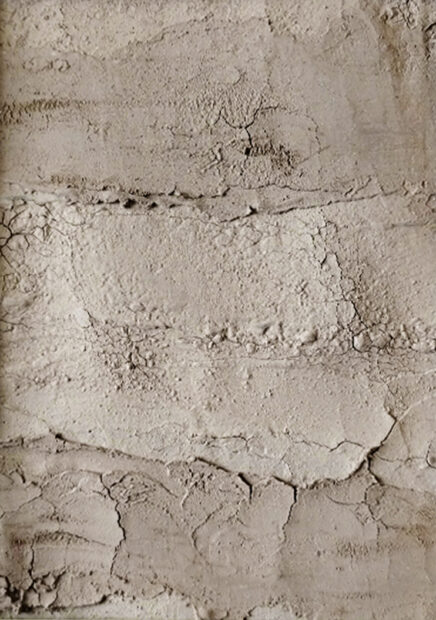

KG: My clay drawings are another way of observing the ground and then bringing it to the forefront of our attention. I explore the unique qualities of clay to recreate what I see. For example, in some of my drawings I focus on the dry, cracked surfaces that happen when there’s a drought; in others, I pour a thin slip, or muddy water, onto a surface to create a fluid-riverbank type of surface. In some drawings, I create an image of a landscape; in others, it’s about a gesture about what touching land feels like.

The materials I use in the clay drawings range from charcoal and red iron oxide to pencil or ink which I use directly on the clay surface. In this series of drawings, I am specific about showing land as the major theme and how, in my case, in the borderlands, land is not just one thing, it’s diverse. In my previous installations, the cactus sculptures and the clay drawings are always in conversation because they are part of the same ecosystem; in a way, I am dissecting, exploring, finding connections, and asking that viewers ask their own questions about the meaning of land, its history, our role in it, and what it means to them.

Karla García, “Paths Revisited, No. 2,” 2022, raw clay on paper, 4.5” x 6.5 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist

CB: You have also photographed your sculptures within the landscape and created videos of them in nature, visually exploring their further connectedness to the land. How did that idea come about?

KG: I began documenting the cacti sculptures in 2020 while working on the Home and Land Project that I shared at the Nasher Windows series that same year. Through this work, I explored the connection between my history as an immigrant in the U.S. and the cultural history of Mexico embedded in the cactus symbol. This history is part of my identity and my present. After this project, I showed I Carry This Land with Me at Gallery 12.26 in Dallas, which was an opportunity to expand this work. I created the desert landscape’s physical setting, focusing on the direct connection to the land, the body, and memories.

For La Línea Imaginaria, I wanted to go back to my home in El Paso and Juarez and document my work in the physical landscape, which to me means both cities. The wall is an unavoidable presence symbolic of division, and I wanted this conversation to exist in my work. I commissioned a photographer to help me document these pieces and together we worked to make my vision possible.

After documenting the work by the wall, I also wanted to spend time in the open desert, undisturbed by any infrastructure. We headed out to Samalayuca, about 30 miles from Juárez. There, you can see and experience the beautiful open desert with cacti plants in the mountainous region that meet the cool and soft sand of the dunes. We captured my sculptures as being part of it. I wanted my work to be seen as a type of memory of the land, which became the video’s title. The full project was exhibited at the Chamizal National Memorial Center and the Museo de Arqueología e Historia El Chamizal. These two centers were important because they are part of the history of the region where the border was disputed and later agreed to by both nations.

La Línea Imaginaria makes reference to this idea of the cultural divisions we set ourselves — the geographical boundaries, which in the Chamizal region was a river that shifted the border. These “lines in the sand” are how borders historically began, and are imagined constructs we set ourselves. However, in the larger scope of things, the land is beneath and around us and is undivided.

Karla García, “La Línea Imaginaria” installed in “Soy de Tejas” in San Antonio. Photo courtesy Rigoberto Luna and Centro de Artes, San Antonio.

CB: Regarding a different type of engagement with nature and the landscape, I wanted to discuss your current outdoor sculpture commission for Fort Worth Public Art. You have been working on fabricating a stainless steel sculpture that’s inspired by a dandelion. Can you share the title of the piece as well as more on its concept?

KG: I am so excited about this piece coming to life. Our long-awaited project is almost finished. The working title is Seed the Future and it is inspired by a single dandelion flower I saw at the park while researching the site. It caught my attention and I found it quite beautiful. Dandelions are migrating flowers, and this was an important connection for me as a metaphor for how seeds find their way to sail by the wind.

In researching the history of Trail Drivers Park, I learned about the cattle workers who migrated through this region to create an industry that is still part of Fort Worth’s culture today. There was a historic cattle trail that connected Mexico to Texas, which gave the park its name. Cattle, food, workers, and culture migrated within this space. According to community members, their multigenerational neighborhood is about legacy, heritage, hope, and setting roots. Creating a sculpture that incorporated a longhorn design, and the dandelion was the best way for me to symbolically tell their story. The spherical design symbolizes neighbors as one connected community. The sculpture’s steel symbolizes strength and the historical industry, while its reflective quality captures the environment and park visitors today. Seed the Future becomes a tribute to the workers who used to travel here while also connecting the present-day tight-knit community and planting a seed for the next generations.

CB: What advice would you give other artists regarding the process of public art?

KG: To be patient and know that there’s a team behind you, starting with your project manager (shout-out to Michelle Richardson, she’s the best!). Setbacks happen and that’s okay; just keep going. I’ve been very fortunate to work with Brian Wooten and AJ from Stealth Industry. Your subcontractors are the team that you rely on to get this type of work done and installed, so make sure you are working with the right people. There’s a lot of research in just getting the people you need; so again, be patient!

CB: When is the anticipated date for the installation of Seed the Future and where in Fort Worth will it be located?

KG: We are set to install this summer, final date to be determined. It will be at Trail Drivers Park in Fort Worth (1700 NE 28th St, Fort Worth, TX 76106), on the north side of the park.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.