Installation view of “Summoning Memories: Art Beyond Chinese Traditions,” Asia Society Texas, February 10–July 2, 2023. Photo © Alex Barber

Hidden under an unassuming (read: dry) title in what is technically not a designated art space, Summoning Memories is a show that inspires return visits like no other in this past season. Curated by Susan Beningson, a relentless enthusiast who, for a time, oversaw the Brooklyn Museum’s Asian collections, the exhibition presents more than thirty artists under a welcomingly wide banner of “Chinese-speaking.” This distinction is crucial for the show’s scope. It’s not just China, it’s also Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the U.S. The connecting thread is tradition, understood inclusively to encompass wildly different approaches to landscape, ink painting, and myth.

When the artists install formal invention into the traditional practices, the works turn out straightforwardly beautiful. Zheng Chongbin’s monumental New Six Canons (2012) upgrade a 5th century painting tractatus for the current century through a process of mixing acrylic and ink that creates evocative swirls and textures, resulting in an alchemic marriage between gestural abstraction and landscape. Yang Yongliang’s digital collages substitute mountains for high-rise residential buildings, following the outlines of traditional landscape painting and thus fusing man and mountain in a way that brings Chinese natural philosophy into the current moment. Taihu Rock of the Liuyuan Garden by Liu Dan could be a Song dynasty work, so respectful it is of the centuries-long conversation with minerals.

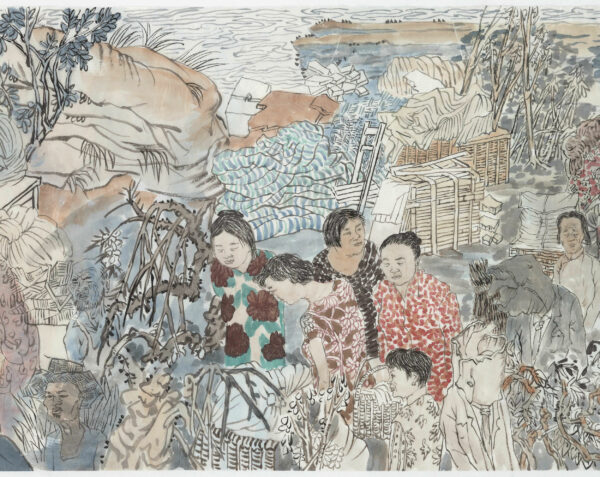

Yun-Fei Ji, “The Three Gorges Dam Migration(detail),” 2008, ink and watercolor on xuan paper mounted on silk. Courtesy the artist and James Cohan Gallery

Most of the better-known artists on display effortlessly combine exquisite technique and delicious —if sometimes grotesque — irony. The older the artist, and the more time she’s actually spent in China, the more layers of self-reflection and circumvention of tradition are displayed. That is not surprising if you know a bit of China’s recent history.

For the West, “tradition” is a portmanteau for ways of living and making that survived the industrial era. Tradition is often seen as either backward, as in the case of the heteronormative nuclear family, itself a recent invention by the factory owners to keep the labor force in check, or mysteriously elusive, as in New Age sympathies towards the various non-Christian, non-white communities. In China, tradition is more fluid. During the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s, when activists of the Red Guard fought a bloody war against the Four Olds, historic ink painting was seen as a reactionary medium, its practitioners banished from exhibition halls and the artistic profession itself.

Later, the newer generations took up what was left of the distinguished ancients and added new critical outlooks, reimagining the practice through different levels of engagement with waves of modernization, either Communist or market-driven. Wang Fangyu’s The Past Weighing on the Present (Gu Jin) (1991) could be the show’s summary: Fangyu, who emigrated to the U.S. in 1945 and taught at Yale, positioned the hieroglyph for “past” over the one for “present,” so that “past” is sure to crush the “present,” or at least do some substantial damage.

Sun Xun, “The Time Vivarium-11,” 2014, acrylic and ink on paper mounted to aluminum. Pizzuti Collection

Incidentally, damage is a topic the artists do not shy away from. An impressive gallery is dedicated to Three Gorges Dam, a grandiose infrastructure project that took the lives of thousands and relocated millions. Wolf Smoke (Smoke Signals) (2006), a painting by Lui Xiaodong, shows a tragic episode of the construction in a mockingly Realist style. Yun-Fei Ji’s Three Gorges Dam Migration (2008), an epic horizontal scroll, reimagines the flooded plains around the dam as a meeting place for the spirits of ancestors and assorted demons, who have to remain in place as they are, in many ways, its inalienable history. This is one of the show’s many masterpieces that rewards close reading.

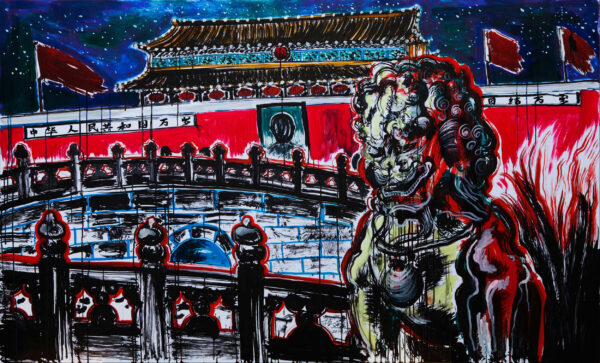

Beyond the Dam, Sun Xun’s colorful paintings take Beijing’s Forbidden City as their subject, but the portrait of Mao in one of them is substituted by a black silhouette. This gesture puts emptiness at the center of China’s primary architectural ensemble of power, reminding us that leaders are but shadow projections of history. Two works by China’s leading conceptual photographer, Hong Lei, place dead birds in pearl and turquoise necklaces on the pavement of the Forbidden City. It’s a dark riff on Chinese painting tradition and a comment on its relevance: birds are supposed to be depicted as if they can fly off paper, but Hong Lei’s photographs connect them with the Western tradition of moralist metaphor.

Installation view of “Summoning Memories: Art Beyond Chinese Traditions,” Asia Society Texas, February 10–July 2, 2023. Photo © Alex Barber.

Other artists plunge into the depths of satire. Liu Wei, one of the proponents of the aptly titled Cynical Realism movement, which was described by Lin Xianting as “collective senselessness and rogue humor,” painted satirical send-offs of Socialist Realism in the 1990s, and later switched to garish semi-abstract guignol. His 21st century work, displayed here, is a beautiful and frantic attempt to summarize everything that happened to art in general for the last twenty or so years.

A selection from 180 Faces (2017) features several imagined portraits, or self-portraits, that quote old masters from China, post-modern painting from the West, and Paul Cezanne, one artist from the Modernist canon who is sometimes seen to be closest to the core principles of Chinese painting. In Untitled No. 6 (Flower) (2003), Liu Wei combines teenage slang, iconographic stereotypes, and traces of ink mastery in a flurry of overlapping sensations. Hong Hao’s Selected Scriptures (1992) is a dystopian world atlas that shows the planet’s catastrophic future under accelerated capitalism. A selection of works by Xu Bing are as laborious as they are tongue in cheek: in Introduction to Square Word Calligraphy (1994-1997), the artist invents a new way of writing English through hieroglyphics, bridging the gap between the sign systems.

Yang Yongliang, “Imagined Landscape, Rabbit,” 2022, Giclee print on fine art paper. Courtesy the artist.

Finally, the younger generations have their own approaches, often placing themselves at the crossroads of memory and identity. For The One in My Dreams, Peng Wei rereads Chinese literary classics, such as Pu Songling’s 18th century ghost stories, to foreground female protagonists. Ren Light Pan documents the start of her transgender passage by sleeping on canvas dripped with ink. Her other work in the show, All Crying is Painting – Irvine, Ca. 01.14.15 (2015), mixes alcohol, water, and ink to create a rhythm of organic shapes that hover between water ripples and rocks. This painting marks the inexhaustible spring of tradition that allows itself to be reconstructed, again and again, from diametrically opposed points of view. And no wonder: since the start of Chinese art, artists have stressed the importance of balancing one’s breath with the movement of the brush. Breathing beings change, and so does painting – in Summoning Memories, it seems ready to adapt to any personal and political transformation.

Summoning Memories: Art Beyond Chinese Traditions is on view at Asia Society Texas through July 2, 2023.