Having previously worked at the Dallas Museum of Art for over six years, I walked by Rufino Tamayo’s El Hombre countless times. While its deep blue sky and angular forms caught my eye, I never took the time to fully appreciate the piece or consider its significance; instead, it quickly went from being a unique painting to a fixture of my workplace. Now, with the benefit of time and retrospection, when I think about pieces in the museum that have stayed with me, El Hombre is one of them. On a recent visit to the DMA, I spent some time with the work and, with the help of a former colleague, dug into the painting’s history.

In person, the piece was much larger than I remembered. In the DMA’s Hamon Atrium, El Hombre is presented alongside other monumental works, including Bash Bish Falls by Cy Gavin, Paper Clip by James Rosenquist, Skyway by Robert Rauschenburg, and the iconic Hart Window by Dale Chihuly. The works hold the large open area well and the specific painting pairings speak to each other: Rauschenberg and Rosenquist’s collage aesthetic and Gavin and Tamayo’s abstracted forms. This presentation, too, must partly be out of necessity — there are few other logical spaces in the museum for these to be on long-term display.

Rufino Tamayo, “El Hombre,” 1953, vinyl with pigment on panel, 216 x 126 inches. Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas Art Association commission, Neiman-Marcus Company Exposition Funds

Tamayo’s looming eighteen-by-ten-foot piece depicts an abstracted man whose feet are planted firmly on the ground as he reaches up toward the night sky. The ground the figure stands on is a deep brown, and the figure’s body is rendered in similar earthy shades, combined with ochres and reds. The figure’s feet are literally connected to the earth as if he emerged from the ground. In the darkness at the figure’s feet is a black dog with a small white bone, and in the vibrant blue sky, a white crescent moon-like shape hangs among a handful of stars, which the artist has connected to form a constellation. In the museum’s 2003 publication, Dallas Museum of Art, 100 years, curatorial assistant Lauren Schell notes that Tamayo originally considered titling the piece Man Excelling Himself.

The composition and message seem straightforward — a symbol of humankind, connected to the reality of this world, aspires for knowledge beyond its grasp — however, when considering the context in which this piece was originally created and the culturally-specific references within the work, it is much more complex. El Hombre, like much of Tamayo’s oeuvre, combines western styles with Mexican aesthetics to create a work with universal appeal that is ultimately reflective of his cultural identity.

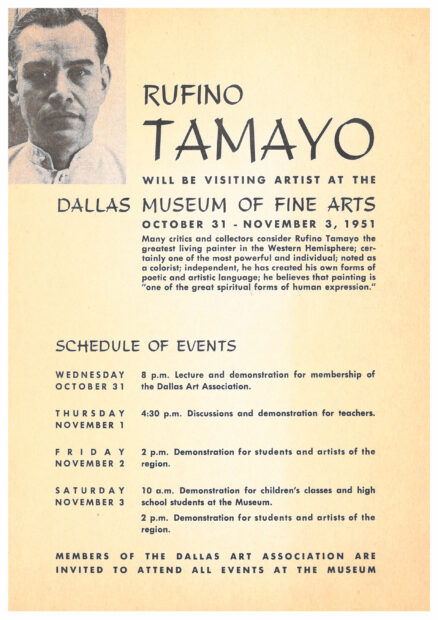

Rufino Tamayo Visiting Artist Announcement from the Dallas Museum of Art. Courtesy of the Dallas Museum of Art.

In 1951, Tamayo was invited to the DMA (then the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts) as a visiting artist. The four-day event of his visit included a lecture and demonstrations for educators, artists, and school-aged students. The following year, Dallas businessman, philanthropist, art collector, DMA Trustee, and son of Neiman-Marcus co-founder, Stanley Marcus, commissioned Tamayo to create a large-scale portable mural to be displayed at the 1953 State Fair of Texas. At the time, Marcus was President of the Dallas Art Association, a civic organization founded in 1903 to support the visual arts in Dallas.

Tamayo completed the three-panel painting in Mexico City, where it was displayed in August 1953 before being shipped to Dallas. At the State Fair, El Hombre, was part of a larger exhibition which brought together art and science in an exploration of the different forms of space — from the physical to the astronomical. The State Fair of Texas Art Exhibition included painters depicting scenes and still lifes of interior spaces in trompe l’oeil, a portable Spitz planetarium operating under a twenty-four-foot dome, blueprints and photographs of designs by architects, and in-the-round works by sculptors. In this context, rather than merely acting as a metaphorical reference to reaching for the stars, El Hombre, painted just before the start of the space race, reflected a wider cultural interest in looking beyond our known world.

In art historical terms, Tamayo is often discussed as being at odds with “Los Tres Grandes” or the three greats — Mexican modernists Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. While Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros were steeped in Mexican nationalism and strived to create and present a singular nationalistic aesthetic, Tamayo lived abroad (in New York City and Paris) and drew inspiration from beyond his home country.

Tamayo’s work does not fit into the traditionally perceived Mexican modernist style, which is often narrowly considered as figurative paintings depicting activist and revolutionary scenes. But Mexican modernism is much more than this. It is bigger than “Los Tres Grandes,” and includes artists like Carlos Mérida and Gunther Gerzo, both of whom combine abstraction with Pre-Columbian aesthetics. Similarly, Tamayo used the visual vocabulary of western movements, like Cubism, in conversation with Indigenous Mexican imagery and styles.

Viewing Tamayo’s work solely through a western lens does a disservice to the art and the artist. El Hombre, in particular, is often discussed as a rendering of a universal topic in a western style. However, it is an oversimplification to assume that Tamayo’s work does not specifically and purposefully draw on Pre-Columbian iconography. As a young man, Tamayo headed the Department of Ethnographic Drawing at the Museo Nacional de Arqueología in Mexico City. In this role, he drew the museum’s Pre-Columbian objects. Throughout his lifetime, Tamayo would integrate styles from Pre-Columbian art and artifacts into his own work, albeit, at times, subtly. Additionally, he collected Pre-Columbian art and in 1974 he turned his private collection into a public museum, the Rufino Tamayo Museum of Pre-Hispanic Art.

The colors of Tamayo’s El Hombre are deeply rooted in Mesoamerican art, which often used red cochineal and añil blue. In the early 1500s, this highly saturated red color, made from crushed cochineal insects, was quickly recognized by colonizers as a valuable resource and was exported to Europe for fabric dyes and paints. Similarly, añil blue, a rich indigo color made from a native plant (Indigofera suffruticosa) and used in Mesoamerican textiles and paints, was also exported from Mexico to Europe. According to the short documentary video Tamayo, el hombre, the artist referred to the colors used in El Hombre as his “Mexican palette.”

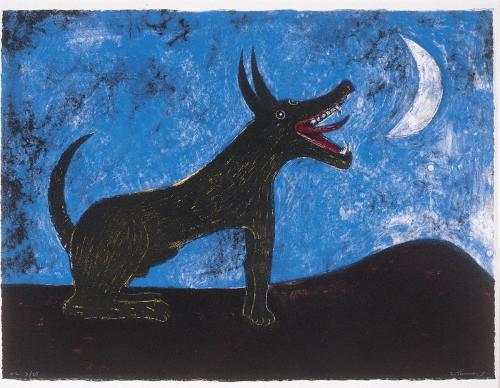

Rufino Tamayo, “Perro de Luna,” 1972, lithograph, 57 x 77 centimeters. Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Gift of the Foster Family Trust.

In a description provided on the DMA’s website, it is suggested that the dog in the painting serves as “a reminder of terrestrial limitations,” perhaps because both the dog’s and the figure’s feet are depicted as coming out of the earth. However, the barely visible dog resembles Tamayo’s other depictions of Xoloitzcuintle, the hairless dog native to Mexico. Aztecs believed these dogs guarded the living and guided the souls of the dead through the underworld. With this added context, it seems more likely that the dog at the figure’s feet is there as a guardian and companion.

Rufino Tamayo, “El Hombre,” 1953, vinyl with pigment on panel, 216 x 126 inches. Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas Art Association commission, Neiman-Marcus Company Exposition Funds

Though Tamayo’s work hangs naturally among artists like Rauchenburg, whose piece in the museum is inspired by cultural events like the space race, or Gavin’s, whose intensely colored abstracted landscape features shadowy figures, his visual vocabulary draws on Indigenous Mexican cultures. These references are at times obscured by the oversimplification of “Mexican aesthetics” seen through a western lens. So, while El Hombre has a universal appeal, it is also a uniquely Mexican work of art.