Material culture is an ever-present but often overlooked aspect of life. It refers to the objects that come to define a society and make the values, beliefs, and traditions of that society manifest. As the title of an exhibition, “Material Culture” lays out a humble and monumental task all at once. In her show at The Grace Museum, Houston-based artist Anna Mavromatis takes the materials of daily life and uses them as source materials for her commentary on United States American values, both historically and presently.

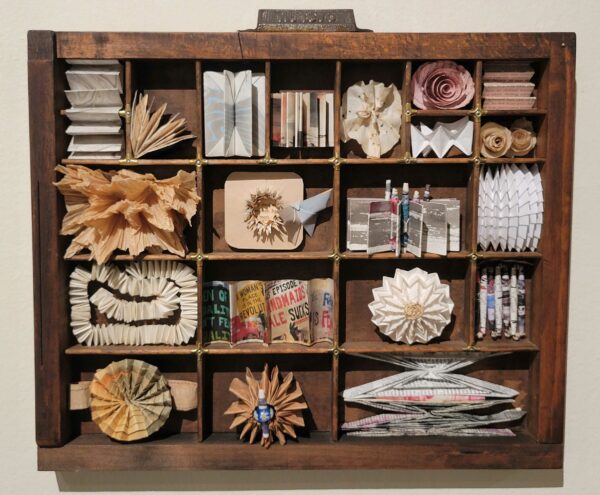

Anna Mavromatis, “Cabinet of Curiosities,” 2019, paper objects created by hand arranged in a vintage printer’s drawer. Courtesy of the artist and Barbara Davis Gallery

Reminding visitors of the long history of display by Western collectors and museums, Mavromatis provides her own Cabinet of Curiosities. Held within a wooden printer’s drawer that has several small compartments to sort the wares of her trade, the artist arranges multiple works of hand-folded and rolled paper.

While this certainly serves as a tidy way for Mavromatis to show off her masterful technique and artistry with a material as humble as paper, it also subtly comments on ideas around womanhood in the Western world. Floral motifs abound throughout her cabinet, from a rolled pink paper rose at the upper right, to a white blossom a few compartments lower, and a floral band at the bottom left. The work also reminds visitors of the struggle for gender equity within the art world by highlighting the material that women artists of earlier generations would have most readily accessed. It is only in the past two centuries that art schools admitted women into their programs, and even then, access to certain advanced lines of study were initially restricted to prevent corruption of their expected innocence.

For many women prior to the twentieth century, decorative arts, textile works, and illustration on paper would have been the primary forms of art they could’ve made. Even within these gendered limitations, it is important to remember the class dynamics that would have further impacted women’s access to the tools for making art, rendering paper the most viable medium for many women artists. Presently, arts institutions are carving out a space for these artworks, previously denigrated as craft, and bestowing the recognition these art forms have long deserved.

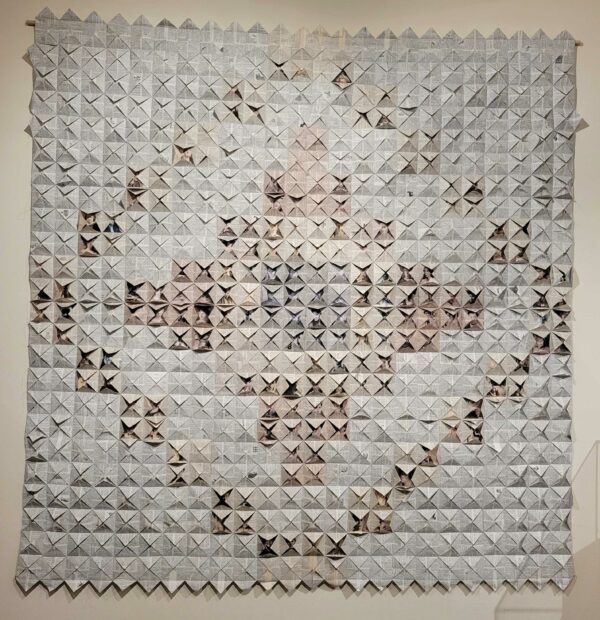

Anna Mavromatis, “Hidden Figures,” 2021, 576 squares cut from an old dictionary, dyed, folded and stitched into a six-foot square. Courtesy of the artist and Barbara Davis Gallery

A centerpiece of the exhibition is Hidden Figures, a paper quilt created with 576 individually folded paper squares, similar to the paper fortune tellers many children create with hopes of getting a glimpse into their future. Slightly opened, the paper squares take viewers on a journey into the past with the faces of several women writers, scientists, inventors, artists and activists peeking through.

Mavromatis has imbued this work with meaning on several levels. She has taken the time to tone some of the squares with teas and wine to provide just enough color to construct diamond patterns, transforming the individual paper squares into a quilt. The quilt has a long tradition in the United States, serving as a project that brought women together for fellowship. Here, the compilation of all these women’s faces does provide fellowship and encouragement to the many women who are still traveling along their paths. It is also important to consider how these women and their accomplishments contributed to the very fabric of this nation. Although in many cases, their work — like their faces in this artwork — has been somewhat obscured and hidden from view in the canonical history of the Western world.

Over the past 50 years, great efforts have been made to revise the histories that have largely erased women from narratives of innovation and progress. Yet, Mavromatis’s work cautions us not to start self-congratulating too soon. How many of the figures do we know today? Where do we learn about these women? She provides the images and biographical information she compiled as research and source material for this piece alongside her artwork. This raises a question similar to those posed about exhibitions solely of women artists: when will supplemental texts highlighting women no longer be necessary, because they have finally become so thoroughly embedded in the canon of writing about United States history?

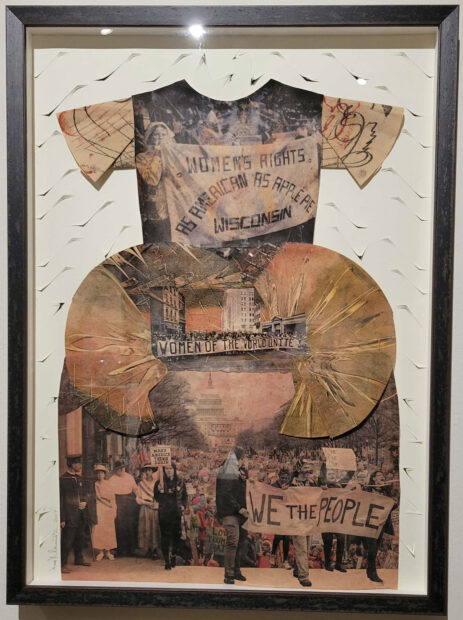

Anna Mavromatis, “Apple Pie,” 2018, toned cyanotypes, monotypes with archival pigment prints of historical images obtained from the National Archives collaged into the form of a girl’s dress and mounted on a cut-out patterned background. Courtesy of the artist and Barbara Davis Gallery

In Apple Pie, Mavromatis draws from her background in clothing design as she continues her exploration of the long legacy of women’s struggles for rights and equity in the U.S. A vintage girls’ dress pattern with bell sleeves and a full, floor-length skirt serves as her base. Across the dress, she has woven together historic images of protests for women’s rights throughout the twentieth century, from suffrage demonstrations to the Women’s March following the election of Donald Trump as president in 2017. The title of the work is drawn from a sign in the historical image across the chest of the dress that reads, “Women’s Rights As American As Apple Pie.” The peach, yellow, and tan tones of the work amplify the Americana apple pie motif.

Anna Mavromatis, “Long Lasting Blues,” 2019, cyanotypes, cutout blossoms with stitching collaged into a dress form and mounted on a cut-out patterned background. Courtesy of the artist and Barbara Davis Gallery

When looking at women’s history and movements in the U.S., there is often a foregrounding of the experiences of White, middle-class, heteronormative women. Yet, Mavromatis has taken care to acknowledge the contributions of women of color and to remind visitors that many women had multiple fronts to fight on when seeking greater equity in this nation. A great example of this is Long Lasting Blues, the artwork that first pulled me into this exhibition. In this piece, Mavromatis again employs a vintage child’s dress pattern, but has toned it blue as a nod to the popular African American musical genre of the blues.

Across the skirt, one finds images of protests for integration in schools as well as the home, in the form of the legalizing of interracial marriage. Black power fists are layered onto the image, along with flowers and the symbols for male and female. It is interesting to encounter this work in the summer of 2022, when these struggles should seem distantly tucked into the past. However, this is also the summer that the United States House of Representatives has felt it necessary to codify interracial marriage, for fear that such rights that had seemingly been settled are no longer so certain. The long-term standing of rights of individuals who aren’t represented by the simple binary of male and female gender symbols also feels unresolved in the present year, adding another layer of meaning into this artwork.

Anna Mavromatis, “Perpetual Dilemma,” 2021, three-dimensional dress made of recycled coffee filters and vintage book pages, hand stamped with words of ambiguity: yes, NO!. Courtesy of the artist and Barbara Davis Gallery

This is what makes art so fascinating, and exhibitions so relevant. While an artist certainly approaches their creations with particular intentions, the rapidly changing state of society can drastically alter how we as viewers create meaning when standing in front of them.

Another perfect example of this is Perpetual Dilemma. For this artwork, Mavromatis takes pages of text from vintage books, paired with tinted coffee filters, to create another vintage-style dress form. Coffee filters are found in many works in this exhibition and it is truly exceptional the delicate texture they provide to the artist’s works — in this case, flowing down the dress like ruffles.

The dress form is such a resonant theme for Mavromatis, because of the important role it has historically played in the lives of women by communicating information about status, family, and in many ways, potential as a future wife. The true impact of this work comes from the text Mavromatis stamped across the chest and sash that hangs down from the waist to the base of the skirt. It alternates “Yes” and “No,” a commentary on the challenging balance women face between being desirable while appearing chaste. As courts and legislatures continue to re-decide the rights and responsibilities of women, particularly in the area of bearing children, the poignancy of this subtle and delicate work is quite powerful.

Overall, this exhibition invites visitors to assess how everyday items, like books, coffee filters, paper, and old photos, tell the histories of a society. In this case, these items speak volumes about women’s positions in United States society in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. What is most fascinating about these artworks is that they remind us all of how relevant the material culture of the past still is in the present day.

Values and beliefs can be slow to shift. The fact that many of the concerns displayed in the historic images sourced for Mavromatis’s artworks have returned to the fore today shows the power of objects, everyday and artistic, to reflect culture and indicate how far or little it has progressed.

Anna Mavromatis: Material Culture is on view through September 17, 2022 at The Grace Museum in Abilene, Texas.

3 comments

Working with Anna Mavromatis to curate this exhibition was such a great experience. As you can see she has much to say and a hundred masterful ways to say it.

Anna is a master at her work, and her delicacy and elegance shows in every fold and crease.

Exceptional creativity aptly described. Greatly admire the intentions of the artists work. Looking forward to the exhibit!