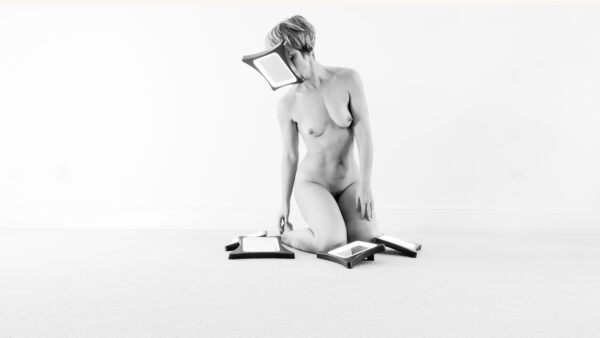

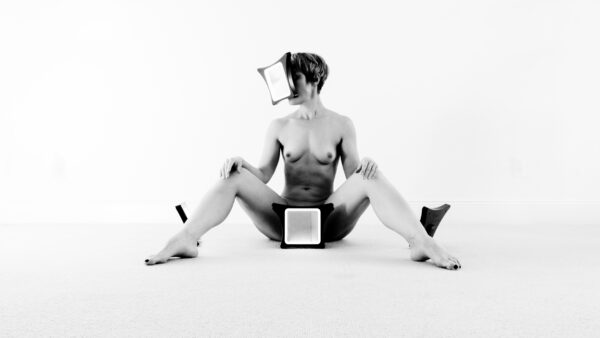

“Focusing Screen” by Sarah Sudhoff, on view as part of the Window Dressing series at ICOSA, Austin. Photo by Sarah Sudhoff

Sarah Sudhoff is a Cuban-American interdisciplinary artist based in Texas, whose work interweaves themes of gender, science, and personal experience using photographs, performance, sculpture, video, animation, and sound. Sudhoff’s most recent project, Focusing Screen, is now on display at ICOSA in Austin, Texas as part of their Window Dressing series.

Focusing Screen depicts Sudhoff employing five VieVision mirrors developed by Nyssa — a self-examination tool for women — as part of a live and recorded performance that amplifies the mystery surrounding the female body, while also offering opportunities for discovery and audience self-reflection. The work was inspired, in part, by Sudhoff’s own experience of the state-regulated medical system and Texas’s regulations restricting access for women to basic healthcare.

In our conversation, Sudhoff discusses conceiving Focusing Screen and its development into the Window Dressing space at ICOSA, as well as past projects related to the evolution of the piece itself.

Caroline Frost (CF): When did the opportunity to show at ICOSA arise?

Sarah Sudhoff (SS): After I performed the performance piece El Recuerdo in May 2021 at my gallery, Nancy Littlejohn Fine Arts in Houston, it caught the attention of the ICOSA group. One part of the piece involves being suspended from the ceiling in Shibari rope, which just isn’t feasible in ICOSA, so we settled on a performance for their Window Dressing series.

There were also many things happening in my own life. Many years ago, I was diagnosed with HPV, and after undergoing surgery for cervical cancer, I began to photograph and perform in hospitals, morgues, medical museums, and my own doctors’ offices, and I made the work Repository in 2004. Last summer, the HPV returned, forcing me to undergo another cervical biopsy.

CF: And then in September the abortion law passed in Texas…

SS: Right. It was all happening at the same time. That’s when I said to ICOSA “this is what’s happening to me, and this is what’s happening in the state.” I felt the correlation, not just politically and psychologically, but physically, and I felt that the VieVision mirror would be a perfect tool to help me realize my vision for a performance at ICOSA.

CF: Since we’re speaking before the installation opens and before the live performance, can you describe the planned layout and schedule for the show?

SS: It’s a weird but fun challenge where I’ll have an installation running 24/7 that will also have a performance component to it. I have been thinking about what is interesting to have in the space during the week, and what may be removed or re-envisioned for the performance.

Over the three facade windows will be the words “CARE MORE, MORE CARE, CARE MORE” in reflective vinyl. Behind the text, and displayed on the wall, three television monitors will flicker black and white performance stills from a private performance captured as I was developing Focusing Screen.

The mirrors have a stand built into them, and when I was preparing for the performance, I put one in my mouth. I started thinking about how many times I’ve been examined and how many people have looked at me. At times I’ve felt objectified by specific, repetitive medical and gynecological exams, and have become a little numb to the treatment of my body in these spaces. But when I put the mirror in my mouth and bit down on it, I started to play with this power dynamic and regain control over my own reflection. With the mirror covering my face, I started to feel like a physician outfitted with a head lamp, examining other women or other versions of myself.

CF: How will the video installation differ from the live performance?

SS: The video installation will be moving much more quickly. The live performance will be a minimally gestural and controlled piece, whereas the installation will feature performance stills. Each monitor will flash, in quick succession, 37 different poses which will loop endlessly. I want to create organic and yet mechanically rigid movements. It is important to me that anyone walking by the ICOSA window will get a sense of the live performance.

CF: As you were describing it, I was imagining the triadic ballet.

SS: Yes! Because viewers will see aspects of my body, but those aspects will be fragmented and framed by the mirrors. The mirrors are the object of focus, but they also serve as a prop and a surrogate.

CF: Right, the live performance will be much more fluid and organic.

SS: Yes, and in some ways, the live performance will be simpler and in some ways, it will be more intense. Once I saw myself with the mirror on my face, the entire project shifted. Before, the performance was going to focus on the use of the mirror between my thighs. Now, I’m using the mirror to examine my entire body, reflect it back to myself, and use it to frame and shield it from the audience.

“Focusing Screen,” by Sarah Sudhoff, on view as part of the Window Dressing series at ICOSA, Austin. Photo by Sarah Sudhoff

CF: Which you weren’t anticipating?

SS: Not exactly. The original set of images were more playful, flowery, and overtly feminine. That being said, it is all part of the same conversation, but it’s different expressions of the same idea.

I was thinking about the window itself. The audience is not only looking but peering in, yet separated from me. A safe distance perhaps, witness but removed. I can recall standing outside a glass door in the operating room observing the same medical procedure I’d undergone. I had witnessed several other surgeries that day but this view, this vulnerability — a woman seen with her legs in the air, a gaggle of doctors over her vagina while she is passed out — still haunts me.

CF: Of course, the mirrors provide a more direct reflection, but the windows themselves also reflect while simultaneously serving as a barrier between you and the audience.

SS: By choosing to perform behind the window, I become more like a specimen in a lab, creating an intimate yet sterile experience. There is something disorienting and distancing about the clinical nature of the glass, the medical gaze, and the mirror, which I’ll be using to examine myself, and the audience. I want to incorporate the reflective nature of the window and the mirrored vinyl text, and give the audience a reflection back onto themselves. This kind of engagement has always been interesting to me.

I’ve also realized that I’m revisiting different things in my life. When I was in graduate school, I created my Repository project based on my experience with HPV. At the time there was a lot of sexism towards women expressing their sexuality, and generally, people reacted negatively when I told them about my illness. Almost twenty years later I am still able to recall what it felt like, things like how people looked at me, received me — or at least how they did back then. I’ve undergone surgery, abnormal pap smears, and biopsies. When I was pregnant with my son, they weren’t sure my cervix would hold, so every week my doctors had to probe me to make sure it was okay. Then, ironically, there was so much scar tissue from my surgery that not only did my cervix hold, but I didn’t dilate, so they had to go in and manually break the scar tissue after 27 hours of labor.

CF: That’s awful.

SS: Awful. Then, during labor — because I’m just the person that I am — I asked them to bring in a mirror so that I could watch. What’s interesting is that I haven’t used a mirror a lot, but I did in two of my exam videos from Repository.

The first Pap smear I captured was shot into a mirror which manipulated the view of the exam. In another exam video, I watch my own cervical biopsy on a monitor. In this new performance I’m using monitors to once again fragment my body and animate image stills to run like a video, emphasizing the repetitive and mechanical nature of so many of my exams. I used a hand-held mirror in Self Exam, and I had that same mirror during labor. I guess, for me, it’s interesting to bring the mirror back almost 20 years later because I’m dealing with these health issues again. Luckily, the HPV has settled back down, but I have been dealing with it for 20 years, and now this crazy, fun mirror has come out which has been cool to play with.

“Focusing Screen” by Sarah Sudhoff, on view as part of the Window Dressing series at ICOSA, Austin. Photo by Sara Sudhoff

CF: I was also really struck by your use of the mirrors. Beyond your experience using them in your personal life, and in previous bodies of work, I immediately thought of Joan Jonas’ Left Side, Right Side.

SS: In an interview I read with Joan Jonas, she discussed the mirror in the context of her first inclusion of technology in her work. The mirror I am using is a light-up mirror that is more technologically-advanced, and is designed specifically for the body — for the thighs — and I’ll be using it on my body and in my mouth. I was also thinking about Janine Antoni’s Paper Dance, which I was able to see at The Contemporary Austin a few years ago. The performance didn’t use mirrors, but I am thinking about self-care with the use of mirrors. I have also been thinking about what it means to be doing performance with an aging woman’s body, and what that looks like.

CF: Since this is in some ways a direct response to your personal medical history and the abortion law in Texas, what is the significance for this project to take the form of performance, and to have a live audience engaging with you in this way on these topics?

SS: I think it makes us all a witness to what is happening, or to participate in a conversation, at the very least. Even though I won’t be able to hear the audience because they won’t be next to me, I will still see them and feel them, and that will influence me. Who knows what’s going to happen, but whatever does happen, an audience will see it. There’s no hiding it from anybody. I’m nude and I’m there, and I’m using mirrors and lights to reflect on myself. I’m willingly making myself vulnerable. I think live performance lends itself to saying, “I’m showing up. You show up. This is how I’m showing up to this conversation, how are you showing up to this conversation?”

I think those conversations that are happening — even if they’re in whispers on the outside — may not happen if it wasn’t for performance. Performance is another form of communication, similar to writing or speaking. I speak in visuals. My gestures, body positions, and images evoke emotions and provide clarity far beyond what I could ever say. So, when I see my body and the mirror, it feels like an extension of my internal world and my own inner dialogue. The performance and the mirror are my means of articulating this. I am both sharing myself and my lived experiences with the audience, while at the same time providing reflections on these experiences for myself and the audience. The words “CARE MORE” in vinyl is a message to everybody to care more about your body, to care more about other people, and to care about what happens to other people’s bodies — especially women’s bodies — and to say that we need more access to care. Not only should we care about our own selves, but we should care about the collective.

CF: In your work, the subject is so varied — from medical environments to crime scene evidence and bodily rhythms — but it all remains tethered to the tension between visibility and invisibility. In Focusing Screen, it seems like there is a power dynamic held within the mirror as agency or reclamation of your anatomy, which you have the visibility of, but the audience does not. I’m interested in this idea of an audience member straining to view the reflections you’re creating, or the body movements you’re making, and instead being confronted by their own image. What significance does that hold for you now, before the performance has taken place?

SS: I get quite harsh reactions to the work I make. I expect some of that, but some of it catches me off guard. I want to provide a reminder that people are very quick to make judgments about other people based on whatever they’re going through, and whatever they’re doing with their own life. I think they should stop and realize that whatever they’re thinking about me when they’re trying to look at me to satisfy their curiosity is also just a reflection of themselves. So, are they really thinking that about me or are they projecting their own biases, curiosities, and histories onto me, which I am then reflecting back at them? How are you looking at me as I examine my most private parts that only our doctors and our partners know intimately?

“Focusing Screen,” by Sarah Sudhoff on view as part of the Window Dressing series at ICOSA, Austin. Photo by Sarah Sudhoff

CF: This is interesting because that’s like the essence of who we are if you identify as a woman. I myself, as a cis woman, feel that so much is determined by that anatomy — who we are and how we operate in the world — and it can still seem so unfamiliar. I keep going back to this thematic tension of invisibility/visibility in your work.

SS: I am working on another project for Ivester Contemporary in March and April that involves a vibrator that collects data. Once again, I am exploring female sexuality and female arousal, and what the data/information collected does for me. But how does the rest of the world perceive it? Will it be perceived as pornographic or as research? All of these questions are tied together for me, where it’s all about using my own body as material and data, and my own experiences as ways to work through issues that are all a part of this conversation — not just for me, but for others. I’m trying to remind people that we project any number of things onto other people. That is the reason I want people to see themselves, because whatever they think about women’s bodies, or women’s healthcare, or women’s rights — whatever it is — we are all a part of both the problem and the solution.

Image from “Focusing Screen,” by Sarah Sudhoff, on view as part of the Window Dressing series at ICOSA, Austin. Photo courtesy Sarah Sudhoff

Focusing Screen is on display at ICOSA in Austin, Texas from February 21-26, 2022. Sudhoff’s live performance will take place on Sunday, February 27 at 7 pm. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.